Key Takeaways

- A Web3 wallet address is derived from a private key, not randomly generated.

- Seed generation and custody model form the foundation of overall wallet security.

- Hierarchical Deterministic (HD) derivation enables multiple wallet addresses to be created from a single seed.

- Address formats and derivation paths are specific to each blockchain network.

- Secure key storage and local transaction signing are critical to protecting user funds.

- A reliable recovery mechanism ensures long-term access and builds user trust.

A Web3 wallet address is the public identifier derived from a private cryptographic key, enabling users to interact with decentralized networks, send transactions, manage assets, and authorize smart contract calls. The wallet architecture consists of two major systems: the key system, which deals with custody and signing, and the chain system, which handles address derivation, balance tracking, and transaction monitoring.

Cryptocurrency wallet address generation itself is just a step in a broader pipeline: first the seed is created securely, then keys are derived, from keys come addresses, which are grouped into accounts, enabling signing, ongoing monitoring, and ultimately, recovery. Understanding this pipeline and specifically how a Web3 wallet address is derived and managed is crucial for building secure and scalable wallets in modern decentralized ecosystems.

What Is a Web3 Wallet Address?

A Web3 wallet address is a public blockchain identifier derived from a cryptographic private key that allows users to receive digital assets, sign transactions, and interact with decentralized applications (dApp) across blockchain networks.

Unlike traditional account numbers managed by centralized institutions, a Web3 wallet address is generated through cryptographic algorithms and exists natively on a blockchain. It does not contain personal information and does not require approval from any authority. Ownership of a Web3 wallet address is proven solely by control of its corresponding private key, which authorizes transactions and smart contract interactions.

Each blockchain ecosystem defines how a Web3 wallet address is formatted and validated. For example, Ethereum-based chains use a 20-byte hexadecimal address derived from a secp256k1 public key, while networks like Solana use Base58-encoded web3 public keys generated from ed25519 keypairs. Despite these differences, the core principle remains the same: a Web3 wallet address is the public-facing identity of a cryptographic key pair.

A single wallet seed can generate multiple Web3 wallet addresses through hierarchical deterministic (HD) derivation, enabling users to manage multiple accounts, improve privacy, and interact with multiple blockchains while maintaining a unified recovery mechanism.

A Web3 wallet address does not store cryptocurrency or tokens directly. Digital assets always remain on the blockchain ledger. The wallet address represents the cryptographic authority required to access and control those assets by signing valid transactions with the associated private key.[1]

| Feature | Web3 Wallet Address | Private Key | Seed Phrase |

|---|---|---|---|

| What it is | Public blockchain identifier | Secret cryptographic key | Human-readable master backup |

| Purpose | Receive assets and identify a wallet | Sign transactions and prove ownership | Recover all keys and addresses |

| Visibility | Public (safe to share) | Private (must never be shared) | Private (must never be shared) |

| Generated from | Derived from the public key | Derived from the seed | Generated from secure entropy |

| Controls funds | No | Yes | Yes |

| Used for signing | No | Yes | No |

| Recovery role | None | Limited (single key) | Full wallet recovery |

| Loss impact | No loss of funds | Loss of funds for that address | Total wallet loss |

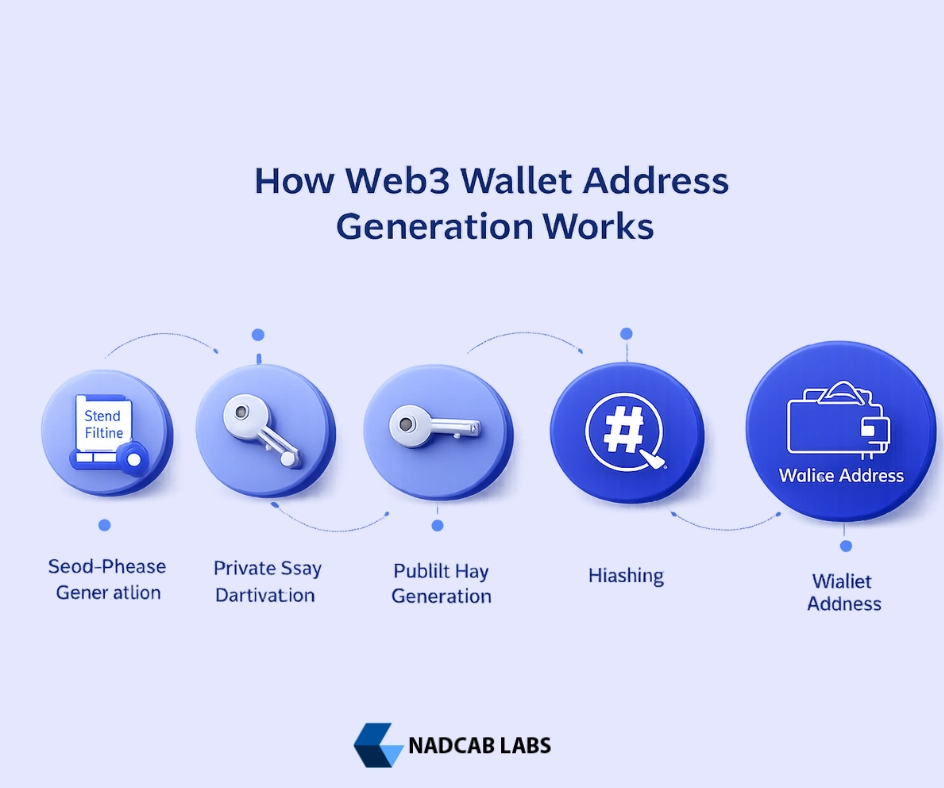

How Web3 Wallet Address Generation Works

A Web3 wallet address is not generated in isolation. It is the result of a multi-stage cryptographic pipeline that begins with secure randomness and ends with a chain-specific public address capable of interacting with decentralized networks.

At a high level, Web3 wallet address generation follows a predictable flow. First, the wallet generates high-entropy random data, which is converted into a mnemonic seed phrase. This seed acts as the root of trust and is used to derive a master key. From the master key, hierarchical deterministic (HD) derivation paths generate private keys for specific blockchains and accounts. Types of wallet like public keys are then computed from these private keys and transformed into final Web3 wallet addresses using chain-specific encoding rules.

This layered approach allows a single wallet to manage multiple accounts, multiple addresses, and multiple blockchains while maintaining a unified recovery mechanism. Understanding this high-level flow makes it easier to reason about custody models, derivation paths, key storage, and recovery strategies discussed in the sections below.

1) Choose the Custody Model First (Because Everything Depends on It)

Before you even generate a single Web3 wallet address, the first architectural decision you need to make is what custody model you will support. This choice affects how keys and addresses are generated, stored, secured, and ultimately recovered.

Non‑custodial wallets, often considered the “real” decentralized wallet experience, put the user in full control of their private keys and seed phrases. In this model, the user’s device holds the keys, never sharing them with any server. All transaction signing happens locally on the device, whether that is a mobile phone, browser extension, or hardware wallet. This gives users complete sovereignty over their funds and addresses but also places the responsibility of secure storage and backup squarely on the user.

Custodial wallets, on the other hand, centralize key storage. In such systems, keys are held on the server side, often within secure infrastructures like Hardware Security Modules (HSMs), vaults, or Multi‑Party Computation (MPC) systems. Custodial systems can automatically generate multiple Web3 wallet addresses for users on the backend, making it easier for exchanges or app‑controlled products to manage deposits and withdrawals. However, they introduce compliance burdens, legal responsibilities, and a much higher security burden because keys are held by the service.

Hybrid approaches attempt to combine the best of both worlds. In a hybrid wallet, the user might maintain a non‑custodial primary wallet, while the platform manages custodial “service wallets” for internal operations like batching or gas payments. This lets product teams optimize operational UX without compromising user control where it matters most. Whichever model you choose shapes how you store, derive, secure, and even back up Web3 wallet addresses throughout the wallet’s lifecycle.

2) Seed Generation Architecture (Root of Everything)

A Web3 wallet address always starts with a seed, a cryptographically secure root that determines every key and address you will ever use. To build a secure seed, you need a robust source of entropy. On mobile platforms like iOS or Android, this means relying on a secure system‑provided random number generators: Secure Enclave or Crypto Kit RNG on iOS and Key store‑backed randomness on Android. For web apps, the window Crypto get random values API is used to generate secure random bytes.

From this secure entropy, a mnemonic phrase (also called a seed phrase) is created using the BIP‑39 standard, a set of 12 or 24 easy‑to‑remember words that represent the entropy with a checksum. This mnemonic is then converted into a binary seed using the PBKDF2 function, which is a recognized cryptographic key derivation method. From this master seed, you can derive all future keys and Web3 wallet protocol.

It is critical that this mnemonic is only shown to the user once and never stored in plaintext anywhere in your system. Instead, when mnemonic or private key material must be stored for local use, it should be encrypted using secure device key stores or secure vault solutions. Proper seed generation and handling ensures that the foundation of your wallet, the root from which every Web3 wallet address comes, is secure.

For a comprehensive explanation of how entropy, mnemonic phrases, and derivation paths connect, see this primer on address derivation from Cube Exchange

3) HD Derivation Architecture (How Multiple Addresses Come from One Seed)

Once you have a seed, you use a hierarchical deterministic (HD) system to generate a tree of keys and addresses. The HD standard, defined by BIP‑32 and extended by BIP‑44, lets a single seed generate many private keys through structured paths, so you don’t need to store every individual key yourself. Instead, the seed and path determine the key.

Here, the 44′ indicates adherence to the multi‑account standard from BIP‑44, coin_type identifies the blockchain (for example, Ethereum is 60’), account represents user accounts, and address_index increments as new addresses are derived. This structure lets a wallet generate multiple Web3 wallet addresses from a single seed securely and predictably across many blockchains and accounts.

Most wallets default to a simple account model where Account 0 is the user’s primary account and uses only the first address index unless the user explicitly requests more addresses. HD derivation is what makes it possible to restore all of a user’s accounts and addresses by simply entering a single mnemonic phrase. If you want to dive deeper into HD derivation and understand how extended keys and paths work, this guide from Cube Exchange explains it.

4) Address Generation Per Ecosystem

After determining your derivation path, you must tailor how you generate the final Web3 wallet address to the specific blockchain ecosystem you are working with.

When generating a Web3 wallet address on EVM‑compatible chains like Ethereum, Binance Smart Chain, or Polygon, the process starts by deriving a secp256k1 private key from the seed. The corresponding public key is then computed and passed through the Keccak‑256 hash function, and the last 20 bytes of that hash become the address. Ethereum adds a checksum via the EIP‑55 standard, giving you the final human and machine‑readable address.

On Solana, wallets use the ed25519 elliptic curve instead. Keys are derived following standards such as SLIP‑0010 to support ed25519 in an HD wallet scheme, and the public key bytes themselves (32 bytes) are encoded using Base58 to create the Solana address.

Bitcoin and other UTXO blockchains have yet another process. After deriving the secp256k1 key, you format it into a script type like P2WPKH (Seg Wit) or P2TR (Taproot) and encode the output with Bech32 or Base58, depending on the format. Each ecosystem’s nuances in address generation must be respected to ensure proper transactions and balance tracking.

For more detail on how address derivation differs across chains, check this section from Cube Exchange.

5) Wallet Data Model (What You Store)

A mature wallet system will contain a robust data model for storing wallet metadata, account structures, and information related to each Web3 wallet address. At minimum, you should track the user’s local identity context, a vault for encrypted seed or key material, logical accounts, and network‑specific chain entities.

Each derived address should include metadata such as the chain identifier, the derivation path, the public key, the address itself, creation timestamps, optional user labels, and an active status flag. Token records should store essential data like contract or mint addresses, decimals, and symbols. Transaction records should maintain the transaction hash, status updates, and other relevant metadata.

Importantly, no system should ever store private keys in plaintext. Encryption and secure storage are mandatory to protect users and maintain trust.

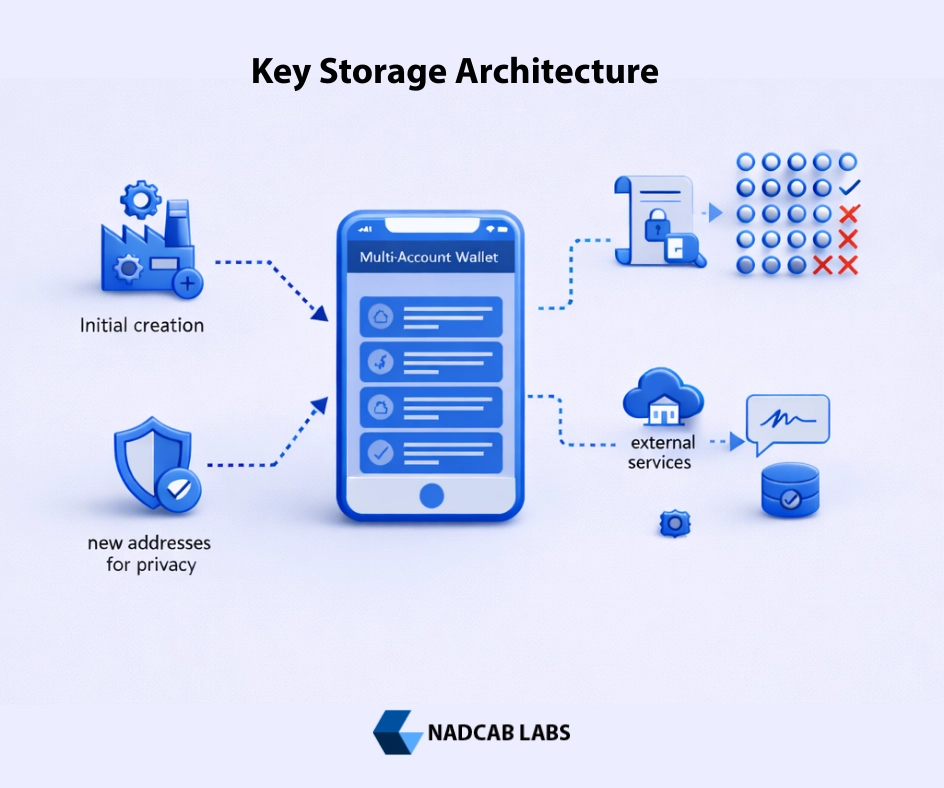

6) Key Storage Architecture (Secure by Default)

The confidentiality of private keys is critical. If a private key is exposed or compromised, any cryptographic system relying on that key can no longer guarantee security, integrity, or authorized control.

The way you store private key material directly affects both security and user experience. For non‑custodial wallets, the seed and private keys must be encrypted using strong algorithms like AES‑GCM and stored within the device’s secure hardware key store. Many wallets also implement optional biometric gating so that signing operations require user authentication through fingerprints or face recognition.

To further harden security, anti‑tamper controls such as detecting jailbreak or rooted devices help prevent exploitation by malicious actors. Integrity checks embedded within the wallet app can detect code tampering at runtime.

Custodial wallets should store keys inside an isolated environment using HSMs or services like Hashi Corp Vault integrated with HSM plugins. An alternative is an MPC/TSS (Multi‑Party Computation/Threshold Signature Scheme) setup, which distributes signing authority across multiple parties. Regardless of the custodian method, signing keys should never leave their secure boundary. Additional layers like detailed audit logging, rate limiting on key access, and strict withdrawal policies further protect assets and Web3 wallet addresses.

7) Address Lifecycle Management (How You “Manage” Addresses)

Managing a Web3 wallet address goes beyond initial creation. A wallet should generate new addresses at specific points in its lifecycle: when a wallet is first created, when a user adds an account, or when new addresses are requested for privacy or operational reasons (especially on UTXO‑based chains like Bitcoin).

When restoring a wallet from a mnemonic, the wallet must scan through derived addresses until it finds a series of unused addresses up to a specified gap limit (commonly 20). This ensures all active addresses and associated transaction history are recovered correctly.

To integrate Web3 wallets with external services such as exchanges or KYC systems it’s often useful to require an ownership proof. This is typically achieved by asking the wallet to sign a server‑provided message using the private key corresponding to a Web3 wallet address, which can then be verified server‑side.

8) Transaction Architecture (Signing + Broadcasting)

Transactions are constructed off‑chain to ensure flexibility and security. Before signing, the wallet fetches necessary context such as the current account nonce or, in Solana’s case, a recent block hash. It also estimates fees and gas, sets any slippage or additional parameters, and prepares the transaction payload.

The signing step occurs strictly within the wallet boundary. In a non‑custodial setting, you should never delegate signing to an untrusted server, because exposing private keys even temporarily increases risk. Good wallet UX often includes showing a human‑readable simulation of the transaction before final signing to help users identify malicious or erroneous operations.

Once signed, the raw transaction is broadcast to the network via RPC providers. The wallet then tracks confirmations, handles potential chain reorganizations, and manages edge cases like replaced or dropped transactions, ensuring the wallet’s view of the network remains consistent.

9) Balance & Token Tracking Architecture

![]()

Tracking balances and token holdings for a Web3 wallet address is essential for real‑time updates within the wallet UI. There are multiple ways to architect this:

One method is RPC polling, where the wallet periodically polls one or more providers to fetch the latest balance and transaction history. While straightforward, this can become resource‑intensive at scale.

A more scalable option is web hooks or event streams offered by providers like Alchemy, Quick Node, or Anker, which deliver near real‑time updates to subscribed addresses. The most advanced option is to run your own indexer, storing events, transactions, and balance changes in databases like Postgres or Click House for complete control and performance.

Token discovery for EVM chains can be accomplished by parsing transfer logs for ERC‑20 tokens, whereas Solana uses its native token program account data to identify token holdings. Caching token metadata such as symbols, decimals, and price feeds improves performance and wallet responsiveness.

10) Recovery Architecture (Most Critical Part)

In hierarchical deterministic wallets, the seed phrase serves as the single recovery mechanism. Re-entering the correct mnemonic allows the wallet to deterministically re-derive the master key, all private keys, and every Web3 wallet address previously generated, restoring full access to assets and transaction history.

Recovery mechanisms depend on your chosen custody model. In non‑custodial wallets, a BIP‑39 mnemonic is the canonical recovery method: entering the correct seed phrase allows users or services to re‑derive every private key and Web3 wallet address exactly as before. Some advanced wallets also use social recovery schemes with guardians and threshold signature setups, especially in smart contract wallets or MPC systems.

Custodial wallets typically recover accounts through identity verification backed by KYC processes, emails, or phone numbers. These systems must enforce strong authentication controls to ensure that stolen credentials don’t lead to unauthorized access.

11) Security Architecture Checklist (Must‑Have)

Cryptographic security is primarily determined by how keys are generated, stored, and protected, rather than by application interface or feature complexity.[2]

To protect a Web3 wallet address ecosystem, your security architecture must include encrypted storage for critical secrets, secure RNG sources for entropy, phishing warnings and transaction simulation features, domain binding to prevent malicious dApp injections, rate limiting and anomaly detection for server‑side actions, forced mnemonic backup UX prompts, supply chain hardening such as signed releases and integrity checks, and logging mechanisms that provide auditability without exposing sensitive data.

12) A Clean End‑to‑End Flow (Single View)

A user starts the journey by tapping “Create Wallet.” The application generates entropy, derives a mnemonic and seed, computes the master key, and from it derives chain‑specific keys and the first Web3 wallet address for each supported chain. The encrypted vault is stored securely, and the UI displays the address. From there, the wallet subscribes to balance updates via chosen infrastructure, builds and signs transactions locally, broadcasts them, monitors confirmations, and updates state. Should the user need to restore the wallet, entering the mnemonic re‑derives every key and address, scanning chain history to rebuild the portfolio and transaction list as originally created.

Build My Crypto wallet Now!

Turn your dream into reality with a powerful, secure crypto wallet built just for you. Start building now and watch your idea come alive!

Complete Overview of Web3 Wallet Address Generation

Generating and managing a Web3 wallet address is not a trivial “create address” function. It is a comprehensive architecture involving seed creation, custody decisions, hierarchical deterministic derivation, multi‑chain support, transaction workflows, balance tracking, recovery systems, and robust security. A proper understanding of each stage ensures a secure, scalable, and user‑friendly wallet that can exist confidently in the modern decentralized ecosystem.

Frequently Asked Questions

A Web3 wallet address lets you receive digital assets, sign transactions, and interact with decentralized applications (dApp) on blockchain networks.

A Web3 wallet address is derived from a cryptographic private key, which itself is generated from a secure seed phrase using standards like BIP‑39 and HD derivation.

Yes if you have the original seed phrase (mnemonic), you can re‑derive all related addresses. Without the seed or private key, recovery is not possible.

Yes a wallet address is public by design. However, sharing your seed phrase or private key is never safe.

An HD wallet can generate billions of addresses from a single seed phrase, depending on the derivation path standards used.

The private key signs transactions for a single address, while the seed phrase is used to derive the master key from which many private keys and addresses can be generated.

Yes, if both wallets support the same derivation standards and paths. Otherwise, you may not see the same addresses.

No assets are stored on the blockchain at that address. The wallet address simply gives you access and control via the associated private key.

If someone obtains your seed phrase, they can recreate your wallet and access all associated private keys and assets, so it must be kept absolutely secure.

Wallet addresses are pseudonymous — transactions and balances are public on‑chain, but they are not directly tied to personal identity unless linked through other data.

Reviewed & Edited By

Aman Vaths

Founder of Nadcab Labs

Aman Vaths is the Founder & CTO of Nadcab Labs, a global digital engineering company delivering enterprise-grade solutions across AI, Web3, Blockchain, Big Data, Cloud, Cybersecurity, and Modern Application Development. With deep technical leadership and product innovation experience, Aman has positioned Nadcab Labs as one of the most advanced engineering companies driving the next era of intelligent, secure, and scalable software systems. Under his leadership, Nadcab Labs has built 2,000+ global projects across sectors including fintech, banking, healthcare, real estate, logistics, gaming, manufacturing, and next-generation DePIN networks. Aman’s strength lies in architecting high-performance systems, end-to-end platform engineering, and designing enterprise solutions that operate at global scale.