Introduction

Shift from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake has become a defining transformation in blockchain technology. In the early days, consensus mechanisms like Proof of Work (PoW) were the standard, powering Bitcoin, Ethereum (until 2022), and other early networks. However, rising energy consumption in crypto, carbon emissions from mining, and growing scrutiny over ESG and blockchain practices have driven the move toward energy-efficient blockchain alternatives such as Proof of Stake (PoS).

Why PoW Became the Norm- and Its Hidden Costs

How Proof of Work Works

In PoW systems, nodes (miners) compete by solving computational puzzles. While this secures decentralized networks, it comes with Proof of Work disadvantages such as excessive energy use, E-waste in cryptocurrency, and concentration of mining power. The first to solve a cryptographic hash challenge appends a block and receives a reward. To “win,” miners run powerful hardware (ASICs, GPUs) continuously, consuming electricity. The system’s security comes from the fact that an attacker would need to control > 50% of the computational power (or hash rate), which becomes prohibitively expensive.

This competition incentivizes overprovisioning – miners want to outdo each other, so they scale hardware aggressively, sometimes with diminishing incremental gains in security per watt.

The Environmental And Economic Burdens

Over time, PoW revealed deep trade-offs. The energy consumption, carbon emissions, and e-waste became subjects of critique.

- A systematic review found that PoW-based cryptocurrencies impose significant environmental impact, especially in carbon emissions, energy demand, and hardware waste. (ScienceDirect)

- Bitcoin mining alone has been compared to national energy use, one study notes that each Bitcoin transaction emits carbon equivalent to driving a gasoline car 1,600–2,600 km. (LSE Blogs)

- The mechanics of mining also produce e-waste. As hardware becomes obsolete quickly (to stay competitive), mining rigs are discarded, often improperly. (Wikipedia)

- A further observation – PoW mining centers tend to concentrate where electricity is cheap or subsidized (for example, areas with surplus hydroelectric power or lax regulation). That centralization raises concerns about geographic risks, regulation, grid stress, and fossil fuel dependency.

The downside is not purely environmental. The arms race in hardware also raises barriers to entry, pushing mining toward more capitalized entities. That can reduce decentralization and shift power toward those with deep pockets.

Thus, the question becomes, Is there a consensus mechanism that retains security and decentralization but consumes orders of magnitude less energy? Enter Proof of Stake.

What is Proof of Stake – and Why It’s More Efficient

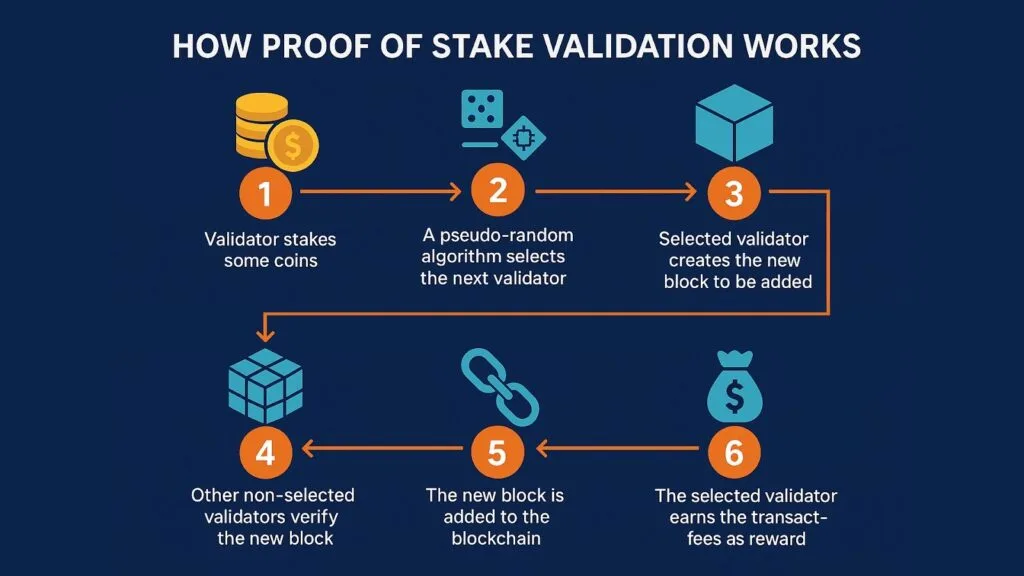

Conceptual Shift – Stake over Work

Under PoS, instead of burning energy on puzzle solving, validators are chosen based on the amount of cryptocurrency they “stake” (lock up) as collateral. If they act maliciously, they risk losing (being “slashed”) some of their stake. The network often picks validators pseudo-randomly, weighted by stake, and sometimes using additional metrics (age of stake, reputation, etc.).

Because there’s no computational race, PoS is inherently lighter on energy.

Energy Savings – What the Data Says

- Ethereum’s transition (“The Merge”) offers a compelling real-world case, an event study observed that energy consumption dropped by ≈ 99.98 % post-transition.

- In industry reporting, many assert that PoS can reduce energy use by up to 99.9% relative to PoW. (Casper Network)

- However, caution is needed – a Forbes piece warns that while Ethereum’s emissions dropped, sustaining that reduction over time (especially under heavy load or price pressures) is not trivial. (Forbes)

- The OECD’s environmental impact study of digital assets also highlights that pure PoS protocols (PPoS) tend to have lower electricity demand and carbon intensities across various networks. (OECD)

So empirically, the shift from PoW to PoS offers compelling energy savings. But the shift isn’t without its own trade-offs.

Challenges, Tradeoffs, and Critiques of PoS

When pushing readers toward PoS, one must honestly address its limitations and debates.

Security Concerns & “Nothing-at-Stake” Problem

One classical critique is the “nothing-at-stake” problem – validators might validate multiple competing forks simultaneously, since there’s no cost (in energy) to doing so. Protocols mitigate this by penalizing misbehaviour (slashing), using finality mechanisms, or requiring lockup periods.

Centralization & Wealth Concentration

Because selection favours larger stakes, PoS can favor those who already own large holdings. Over time, this can lead to concentration of power in a few validators or staking pools. Addressing this requires design choices – limits on stake per validator, curation of validator sets, or mechanisms like delegation (where smaller holders delegate stake to validators).

Incentive & Validator Behaviour

Validators must stay online, follow protocol rules, and avoid downtime or misbehaviour. Designing incentives (rewards vs. penalties) is subtle, too harsh slashing disincentives participation, too lenient invites misbehaviour.

Real-World Durability

While the Merge (Ethereum) is a successful case, we are early in the PoS adoption era. Long-term behaviour under network stress, governance attacks, or economic cycles is less tested.

Sustainability Isn’t Automatic

Lower energy consumption is necessary but not sufficient. Validators may still run on fossil-fueled grids. Some critics argue that too much attention on “energy use” might distract from more nuanced risks (e.g., governance centralization, economic design flaws). That is, PoS is more efficient, but sustainability still depends on where the validators source their electricity and how the protocol design encourages green operation.

The Transition – Stories & Case Studies

Ethereum’s Merge

Ethereum’s switch from PoW to PoS (“The Merge”) is the marquee example.

- The event study noted a ~99.98% drop in energy consumption after the Merge.

- Validators replaced miners rather than the same entities converting hardware. The mining rewards (in USD terms) dropped significantly.

- The transition also impacted supply growth – Ethereum became deflationary in net issuance post-merge.

These facts reinforce that the shift isn’t hypothetical; it has occurred and been empirically measured.

Comparative Networks

- Research in environmental DLT literature often cites IOTA’s energy modelling (though IOTA uses different architectures) to show how non-PoW networks can operate with minimal energy. (arXiv)

- Broader studies on ESG-focused DLT research signal that more projects are leaning toward energy-efficient consensus designs over time.

These examples lend authority and depth to claims about energy efficiency.

Why the Shift Matters – Beyond Energy

The transition to PoS supports blockchain sustainability and may influence token issuance and deflation dynamics. By addressing Proof of Work disadvantages and adopting energy-efficient blockchain practices, networks can align with ESG and blockchain standards while maintaining decentralized governance.

Public Perception, Regulation & Legitimacy

As climate concerns rise globally, regulatory bodies and environmental advocates increasingly scrutinize high-energy crypto mining. A pro-PoS posture may ward off restrictive policies or carbon taxes applied to PoW mining. The shift signals responsiveness to sustainability demands, improving legitimacy among regulators, investors, and the public.

Economic Inclusion & Participation

Lower energy and hardware requirements reduce barriers to entry. More participants (small holders, validators) can engage without massive capital expenditure. This can strengthen decentralization and broaden network participation.

Long-Term Viability of Blockchain

If blockchains are to be sustainable for decades, they must align with resource constraints. PoS helps reduce friction around electricity usage and environmental impact, building resilience for future expansion, scaling, and adoption. To optimize such sustainability and efficiency, businesses can get blockchain related services that focus on energy-efficient solutions and scalable network designs.

How to Evaluate Projects in the PoS Era

If you’re assessing or building a blockchain or protocol, here are practical criteria (anchored in trust and transparency)

- Energy Metrics & Transparency

- Does the project publish validator node energy use (or estimates)?

- Are validators encouraged (or required) to disclose power sources?

- Slashing & Security Design

- Are fork/conflict conditions well defined?

- How does the protocol penalize misbehaving validators?

- Decentralization & Stake Distribution

- What’s the concentration of top validators or staking pools?

- Are there caps or mechanisms to prevent dominance?

- Governance & Upgradability

- How does the network propose and enact protocol changes?

- Is there a transparent governance process (on-chain, off-chain) with accountability?

- Incentive Balance

- Is the reward structure balanced to attract validators without overinflating issuance?

- Are penalties not so harsh as to discourage participation?

- Reputation & Ecosystem Support

- Does the project, its team, or its validators have credible domain standing (papers, developer contributions, known audits)?

- Are there third-party audits, community reviews, and critiques?

By applying these criteria, you move beyond marketing claims of “green blockchain” into verifiable trust.

Conclusion

The shift from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake is not just a technical pivot, it’s a cultural and existential evolution of blockchain. It responds to environmental imperatives, strengthens accessibility, and aligns incentives toward efficiency. But PoS is not a silver bullet. Its security, governance, and socio-economic Tradeoffs must be understood and designed carefully.

The Ethereum Merge illustrates that the energy gains are real, but long-term resilience and legitimacy will depend on transparency, decentralization, and the ability of validators to operate sustainably. As more chains adopt PoS or hybrid consensus models, stakeholders (developers, users, auditors) must scrutinize design and operations, not just slogans. To understand how different blockchain architectures influence such consensus mechanisms, explore our guide on Public, Private, and Consortium Blockchains Types Explained.

Frequently Asked Questions

Yes. Trade-offs regarding security and decentralization apply to PoS networks including possible centralization of power in large stakeholders; the nothing-at-stake problem; and a careful balance of staking rewards and penalties, to keep validators honest.

Ethereum completed something called the Ethereum Merge to reduce energy usage in crypto, reduce the carbon footprint of mining, and support sustainability. The Merge led to faster transactions and improved scaling.

Proof of Work consists of miners using computational power (mining hardware like ASICs and GPUs) to solve complicated puzzles and uses a lot of energy in the process. Proof of Stake selects validator nodes based on how much cryptocurrency they stake and produces a much more environmentally sustainable way to perform blockchain functions.

The benefits of Proof of Stake consist of lower energy consumption, decreased hardware wastage (E-waste in crypto), improved access for smaller participants, and assistance to decentralized governance through equitable validator adversity.

PoS addresses Proof of Work’s disadvantages while supporting sustainability for blockchains, driving long-term viability, supporting all token issuance and deflation strategies, aligns with environmental, social and governance (ESG) and blockchain standards, and offers a more sustainable and accessible model for decentralized networks.

In PoW, mining involves intense energy-consuming algorithms where miners block with each other by expending energy on repeated calculations. In PoS, validators are chosen based on how much is staked so that electricity is expended less often, as evidenced by Ethereum’s electricity use dropping by 99.98%, making it the ‘poster child’ of an energy-efficient blockchain.

Reviewed & Edited By

Aman Vaths

Founder of Nadcab Labs

Aman Vaths is the Founder & CTO of Nadcab Labs, a global digital engineering company delivering enterprise-grade solutions across AI, Web3, Blockchain, Big Data, Cloud, Cybersecurity, and Modern Application Development. With deep technical leadership and product innovation experience, Aman has positioned Nadcab Labs as one of the most advanced engineering companies driving the next era of intelligent, secure, and scalable software systems. Under his leadership, Nadcab Labs has built 2,000+ global projects across sectors including fintech, banking, healthcare, real estate, logistics, gaming, manufacturing, and next-generation DePIN networks. Aman’s strength lies in architecting high-performance systems, end-to-end platform engineering, and designing enterprise solutions that operate at global scale.