Key Takeaways

- DEX architecture is defined first by execution model, not UI or features.

- Chain selection fixes gas, finality, MEV exposure, and execution limits permanently.

- Core contracts must separate creation, execution, routing, ownership, and governance logic.

- Correct AMM math and slippage enforcement define swap safety and user trust.

- Liquidity flows require precise accounting to prevent silent long-term capital loss.

- Indexing and quoting systems are mandatory for real-time UX and routing accuracy.

- Security, monitoring, and governance determine whether a DEX survives production reality.

The first and most irreversible decision in decentralized exchange architecture is the trading model.

This choice is not a UI preference or a feature toggle,it defines the execution semantics, liquidity behaviour, infrastructure complexity, security surface, and even the type of users DEX can realistically serve.

Every downstream component—pool design, router logic, indexing strategy, MEV exposure, frontend UX, and operational cost—is constrained by this single decision. Mature DEX systems do not “experiment” with this choice in production; they commit early and design everything around it.

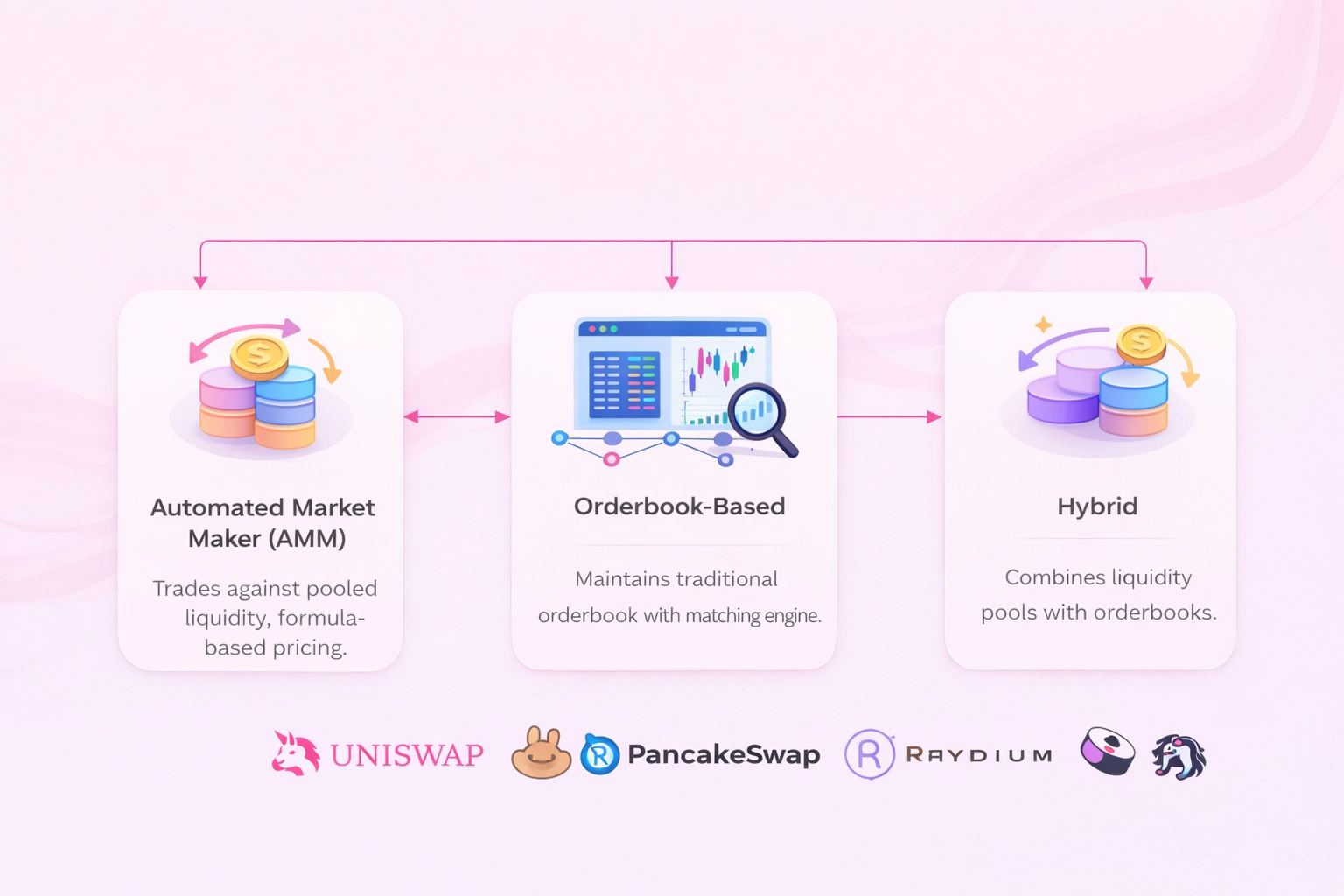

At a high level, all DEXs fall into one of three execution models.

Automated Market Maker (AMM)

The AMM model replaces traditional bid–ask matching with deterministic pricing functions driven by on-chain liquidity pools. Trades are executed against pooled assets rather than counterparties, making execution always available as long as liquidity exists.

This model is favored for permissionless environments because it removes the need for active market makers, centralized matching engines, or persistent order state.

Key characteristics that define AMM-based DEXs:

-

Liquidity is passive and pooled

Any user can become a liquidity provider without managing orders. Capital efficiency is dictated by the AMM formula rather than order placement skill. -

Pricing is formula-driven, not demand-driven

Prices shift based on reserve ratios (v2) or liquidity distribution across ranges (v3), not by matching bids and asks. -

Execution is fully on-chain

Every swap, liquidity change, and fee update is validated by the blockchain, simplifying trust assumptions but increasing gas sensitivity. -

UX is predictable and composable

AMMs integrate cleanly with wallets, aggregators, and DeFi protocols because execution paths are deterministic. -

MEV exposure is structural

Sandwiching and price impact cannot be eliminated, only mitigated through slippage controls, private routing, or UI guidance.

AMMs dominate modern DeFi because they minimize coordination complexity. As a result, most new DEXs start with an AMM core and only expand once liquidity and usage justify additional execution models.

Orderbook-Based DEX

The orderbook model mirrors traditional exchanges by maintaining discrete buy and sell orders, matched by price and time priority. In decentralized environments, this introduces significant architectural challenges.

True on-chain orderbooks are usually impractical due to gas and latency constraints, so most implementations rely on off-chain matching with on-chain settlement.

This model is chosen when precision and trader control are more important than permissionless simplicity.

Defining traits of orderbook DEXs:

-

Liquidity is active, not passive

Market makers must constantly manage orders, cancel stale quotes, and rebalance positions. -

Matching is computationally heavy

Sorting, matching, and maintaining depth is rarely viable fully on-chain at scale. -

Infrastructure complexity increases sharply

Reliable off-chain engines, sequencers, or relayers become critical components. -

Execution quality is superior for professionals

Limit orders, tight spreads, and reduced price impact attract high-frequency and institutional traders. -

Operational risk shifts off-chain

While settlement remains trust-minimized, uptime, latency, and fairness depend on off-chain systems.

Orderbook DEXs excel in environments like Solana or appchains where throughput is high and latency is low, but they demand significantly higher engineering and operational maturity.

Hybrid DEX Architecture

Hybrid models attempt to combine the liquidity availability of AMMs with the execution precision of orderbooks. This is not a single design but a family of architectures with varying trade-offs.

Common hybrid approaches include:

-

Orderbook routing with AMM fallback

Orders try to match against limit liquidity first, then route residual volume to AMM pools. -

Off-chain orderbooks with on-chain settlement

Orders are matched off-chain, but final balances and state transitions are enforced on-chain. -

AMMs with limit-order abstractions

Limit orders are simulated using concentrated liquidity ranges or conditional execution logic.

Hybrid systems aim to evolve liquidity over time without fragmenting the user base. However, they introduce coordination complexity between execution layers and require strict correctness guarantees.

Most successful hybrid DEXs did not launch as hybrid systems they grew into them.

Why Most DEXs Start with AMM First

From an architectural and economic perspective, AMMs provide the fastest path to:

-

Bootstrapping liquidity without market maker agreements

-

Achieving protocol DEX composability

-

Minimizing off-chain trust assumptions

-

Reducing initial infrastructure cost and failure modes

Once liquidity depth, trading volume, and user sophistication increase, additional execution primitives such as limit orders or professional routing can be layered on top without breaking core invariants.

This progression is not accidental it reflects the reality that liquidity precedes execution sophistication, not the other way around.

2) Define the Chain + Execution Constraints

Once the DEX model is chosen, the next irreversible decision is the execution environment. The chain is not “where deploy”, it is the runtime that defines what is possible, what is expensive, what is unsafe, and what must be built off-chain to compensate for on-chain limits.

At enterprise scale, chain selection is an architectural boundary-setting exercise. It determines transaction throughput, fee predictability, state access patterns, indexer design, oracle strategy, MEV exposure, and even how design core contract interfaces. A DEX that behaves correctly on one chain can become economically non-viable or security-fragile on another.

EVM Chains (Ethereum / L2s / BSC)

EVM-based deployment is the default path because of ecosystem maturity, composability, and battle-tested tooling. But the EVM environment comes with a hard reality: blockspace is scarce, MEV is structural, and contract execution is bounded by gas economics.

Core characteristics must internalize:

-

Deterministic execution, but economically constrained

Design must assume users pay for every state touch. Routing depth, pool math complexity, and event emission strategy are constrained by gas cost. -

Mempool visibility creates adversarial execution conditions

MEV is not an edge case; it is the baseline. Swaps will be copied, sandwiched, backrun, and reordered unless provide mitigation paths. -

L2s improve throughput but change trust and finality assumptions

May gain cheaper execution, but inherit sequencer behavior, withdrawal delays, and chain-specific reorg or outage patterns. -

Tooling is enterprise-grade

Auditing workflows, fuzzing, formal verification, monitoring, and indexers are mature. This reduces engineering uncertainty—but does not remove execution risk.

EVM is the safest choice for protocol composability and market reach, but it forces you to architect around gas ceilings and MEV realities from day one.

Solana (High Throughput, Different State Model)

Solana is not “EVM but faster.” It is a different execution paradigm with an account-based state model and explicit constraints around compute and parallelism. The advantage is high throughput; the cost is architectural complexity in how structure state and transactions.

Key constraints that shape DEX architecture:

-

Account model dictates how pools and positions are represented

Don’t freely access global state like EVM mappings; pass accounts explicitly, and state is stored across account structures. -

Compute budget limits become gas ceiling equivalent

Complex swap paths, deep routing, or heavy math must fit into compute constraints. Design for bounded compute, not unlimited logic. -

Parallel execution rewards careful state partitioning

If program forces many transactions to touch the same accounts, kill concurrency. High performance requires designing to avoid contention. -

Rent and account lifecycle economics matter

Storage isn’t “free after deployment.” Account creation, rent-exemption rules, and data sizing become part of the cost model.

Solana can power professional-grade trading experiences at scale, but it requires to engineer around account access, concurrency, and compute budgets rather than gas and calldata.

Cosmos SDK / Appchain (Maximum Control, Maximum Responsibility)

Building a DEX as an appchain is a decision to stop fitting into someone else’s runtime and instead design own execution rules. This offers unmatched flexibility—but it turns protocol engineering into full-stack blockchain operations.

Core implications:

-

Can implement DEX logic as native modules

This can massively outperform smart-contract based designs by reducing overhead and optimizing state transitions at the consensus layer. -

Fee markets and transaction semantics are to define

Can redesign gas economics, introduce custom priority rules, or build fee abstractions that are impossible on shared chains. -

Ops becomes part of the product

Validators, upgrades, governance, chain security, monitoring, incident response, and liveness become ongoing operational requirements. -

Liquidity fragmentation is a real strategic risk

Trade ecosystem composability for sovereignty. DEX becomes a destination chain, which requires stronger distribution and liquidity incentives.

Cosmos SDK is the right choice when DEX is not “an app,” but a core financial infrastructure layer that needs custom execution guarantees.

Execution Constraints Must Lock Before Designing Contracts

After pick the chain, must lock the constraints that determine whether architecture survives production load.

Gas / Fees Model

Fees determine whether DEX is usable and whether router design is viable.

-

High fees force shallow routing and minimal state writes

Multi-hop swaps, complex quoting, and rich event logs become economically painful. -

Low fees enable richer UX but increase spam and abuse risk

Cheap execution invites bots, high-frequency arbitrage, and state bloat if don’t architect guardrails. -

Predictability matters as much as price

Traders care less about absolute fee cost than about whether costs are stable enough to quote reliably.

Finality + Reorg Tolerance

Finality determines how safely can treat “a swap happened” as true.

-

Probabilistic finality requires reorg-aware indexing

Indexer, analytics, and user portfolio history must handle reverted events cleanly. -

Sequencer-driven chains require outage and reorder planning

Must plan for delayed inclusion, temporary halts, or reordered transactions under load. -

UX must reflect confirmation reality

The frontend should distinguish between submitted, included, confirmed, and finalized states. Treating “pending” as “done” creates user loss scenarios.

Max Transaction Size / Compute Limits

These limits decide how much work a single swap can do.

-

Routing depth is capped by execution budgets

“Best price” route is irrelevant if it cannot execute within compute or calldata constraints. -

Complex pool math reduces composability

Advanced math (v3 tick logic, multi-position accounting, dynamic fees) consumes execution budget and may require simplifying trade paths. -

Batching and multicalls have ceilings

Must decide early whether optimize for single-tx UX or accept multi-tx flows for complex actions.

Oracle Availability (If Needed)

Even if AMM can operate without external prices, the moment add features like dynamic fees, stable pegs, perps, or anti-manipulation controls, oracle assumptions become structural.

-

Oracle latency becomes a risk parameter

If oracle updates slower than market movement, it can be exploited. -

Oracle trust model must match hreat model

“Decentralized oracle” is not a binary. must define failure modes: delayed updates, stale rounds, chain outages, or corrupted feeds. -

Fallback and validation logic must be explicit

If oracle input is missing or invalid, protocol must define the safe behavior: pause, degrade, or switch to internal TWAP.

3) Core On-Chain Contracts (The Minimum DEX “Engine”)

An AMM DEX is not “a swap contract.” It is a coordinated set of contracts that split responsibilities so the system remains upgradeable in practice (even if immutable on-chain), indexable off-chain, and safe under adversarial execution. The minimum engine is the smallest set of on-chain components that can (1) create markets, (2) price and execute swaps, (3) manage liquidity accounting, and (4) provide a stable interface to users and integrators.

At enterprise level, design this layer like a protocol runtime: clear module boundaries, minimal trust, and explicit invariants. If merge these responsibilities into one monolithic contract, create an audit nightmare and a long-term maintainability trap.

Below is the canonical AMM engine decomposition.

A) Factory (Market Creation + Canonical Registry)

The Factory is the protocol’s source of truth for what pools exist and which pool address is canonical for a given configuration. It is not a convenience contract; it is what prevents fragmentation and protects integrators from routing into unofficial pools.

Core responsibilities:

-

Pool creation as a controlled primitive

Creates pools only under valid configurations (token ordering rules, fee tier rules, supported parameters). This is where enforce “one pool per pair per fee tier” to avoid liquidity splitting. -

Canonical registry mapping

Stores the deterministic lookup:(tokenA, tokenB, feeTier) → poolAddress.

This registry is what routers, indexers, UIs, and aggregators treat as authoritative. -

Protocol-level configuration surface

If support multiple fee tiers, tick spacing (v3-style), or pool templates, those parameters are validated and emitted here.

Tight rules the Factory must enforce:

-

normalized token ordering (

token0 < token1) -

uniqueness constraints (no duplicate pools)

-

parameter constraints (fee tier must be allowed)

-

event emission for discovery (

PoolCreatedis an indexing contract with the outside world)

B) Pool Contract (Where Value Lives and Swaps Happen)

The Pool is the core execution domain. It is where assets sit, invariants are enforced, prices move, and fees accumulate. In AMMs, the pool contract is effectively the “matching engine,” but expressed as deterministic state transitions.

What the pool must do at minimum:

-

Hold liquidity state

-

v2 style: reserves

(reserve0, reserve1)plus fee accounting -

v3 style: liquidity positions distributed across price ranges, with tick state and fee growth accumulators

-

-

Execute swaps with invariant enforcement

The pool must guarantee correctness under all adversarial ordering and calldata—meaning the pricing logic must not be bypassable through reentrancy or token quirks. -

Expose a stable swapping interface

Routers and integrators depend on predictable function signatures and revert reasons. A pool that is “technically correct” but operationally unpredictable becomes unusable. -

Emit events designed for indexing

Swap, mint, burn, collect events are not optional. They are external ledger for analytics, compliance dashboards, and user portfolio reconstruction.

Pool design realities:

-

Pools must be lean: every extra storage write is permanent cost

-

Pools must be strict: never “support everything” (fee-on-transfer tokens, rebasing tokens) unless explicitly designed

-

Pools are the highest-risk contract: this is where exploits happen (math, rounding, callback abuse, reentrancy)

C) Router Contract (User Execution Gateway)

The Router is the user-facing execution coordinator. It does not define pricing; it enforces user intent (slippage limits, deadlines, routing choice) and orchestrates interactions across pools.

The router exists because users don’t want to:

-

calculate pool addresses

-

manually approve multiple pools

-

manage multi-hop complexity

-

write custom calldata for every swap pattern

Core responsibilities:

-

Multi-hop routing

Executes sequential swaps across pools (A→B→C) with correct token flow and intermediate balances. -

Slippage + deadline enforcement

AcceptsamountOutMin,amountInMax, and deadline constraints to ensure users do not get filled at manipulated prices or after stale quotes. -

Exact-in and exact-out flows

Enterprise-grade DEX routers support both patterns:-

Exact input: user commits amount in, accepts variable out above min

-

Exact output: user commits desired out, accepts variable in below max

-

-

Handling wrapped native tokens

Normalizes ETH/BNB/SOL-wrapped equivalents so UX remains consistent.

Router rules that matter:

-

never trust pool state mid-route unless control the call sequence

-

make reentrancy impossible through strict call structure and state assumptions

-

do not embed “quote logic” in the router; quoting belongs in a separate read-only quoter/simulation layer

D) LP / Position Logic (Ownership, Accounting, Fee Entitlement)

Liquidity is not just deposits; it is ownership accounting plus fee attribution. How represent LP ownership fundamentally changes UX, composability, and indexing complexity.

Two production patterns dominate:

v2 style: LP token (ERC-20 share)

Liquidity providers receive an ERC-20 representing proportional ownership of the pool reserves.

-

Simple mental model: “I own X% of the pool”

-

Highly composable: LP tokens can be staked, lent, used as collateral

-

Less capital efficient: liquidity is spread across all prices

Key implementation requirements:

-

mint/burn shares correctly under invariant constraints

-

lock minimum liquidity to prevent division edge-cases

-

track fee implicitly via reserve growth (or explicit fee tracking if separated)

v3 style: NFT positions (range liquidity)

Liquidity providers own specific price ranges, represented as NFTs with individualized fee growth accounting.

-

Capital efficient: liquidity concentrated near active price zones

-

Complex accounting: each position has fee growth snapshots and tick dependencies

-

Harder UX: users must manage ranges, rebalancing, and impermanent loss dynamics actively

Key implementation requirements:

-

tick math and price range validation

-

per-position fee growth tracking (global → per-tick → per-position)

-

position manager contract to mint/modify/burn NFTs safely

In enterprise systems, treat LP accounting as a financial ledger. Any edge-case error becomes a direct loss event.

E) Fee + Protocol Controls (Optional, But Practically Always Present)

Even “fully decentralized” DEXs usually implement protocol-level fee controls because:

-

they need treasury funding for audits, incentives, and operations

-

they need upgrade governance pathways (timelocks, parameter changes)

-

they need risk control mechanisms (pauses, allowlists for specific features)

Common fee/control components:

-

Protocol fee switch

Ability to divert a portion of LP fees to the protocol treasury. This is usually gated by governance + timelock. -

Fee collector / treasury

A dedicated contract to receive fees, distribute incentives, or route to DAO-controlled addresses. -

Emergency controls (minimal and scoped)

If must include pause switches, scope them tightly:-

pause new pool creation

-

pause specific routing functions

-

never allow admin withdrawal of user funds

-

-

Whitelist/blacklist hooks (only if required)

These should be treated as regulatory or business-specific constraints, not default features. Every hook increases attack surface and governance risk.

The golden rule: protocol controls must not become hidden custody. If an admin can move user funds, are not building a DEX ,building an exchange with smart contracts.

The Contract Boundary Map (How These Components Interact)

A clean AMM engine interaction chain looks like this:

-

Factory is the registry and pool creator

-

Pool is the execution state machine holding value

-

Router is the user intent orchestrator

-

LP/Position system is the ownership + fee attribution layer

-

Fee/controls are governance and revenue primitives, isolated from swap correctness

This separation is what allows the DEX to scale safely: audit scope is clearer, indexing becomes reliable, and integrators have stable touchpoints.

4) Token Handling + Approvals (Security-Critical)

In an AMM DEX, “token transfer” is not a trivial operation—it is the highest-frequency, highest-risk action protocol performs. Most DEX exploits are not caused by exotic math; they come from incorrect token assumptions, approval mishandling, callback/reentrancy surfaces, or supporting token behaviors the protocol was never designed to price correctly.

Enterprise-grade DEX design treats token interaction as a dedicated security layer with strict standards. The objective is simple: every asset movement must be deterministic, auditable, and invariant-safe, even when tokens behave in non-standard ways.

This section defines what must be standardized before ship.

Safe Transfer Wrappers (Because ERC-20 Is Not Actually Standard)

The ERC-20 “standard” is inconsistently implemented in the wild. A non-trivial number of tokens:

-

do not return

boolontransfer/transferFrom -

return

falseinstead of reverting -

revert on zero transfers

-

charge transfer fees or burn amounts

-

modify balances in rebasing mechanics

-

block transfers to/from specific addresses

If DEX assumes “ERC-20 always returns true,” designing for a fantasy environment.

What enterprise DEXs do:

-

Use a hardened safe transfer library

-

On EVM, this means wrappers that treat missing return data as success only if the call didn’t revert, and treat explicit

falseas failure. -

Every token move should either succeed deterministically or revert cleanly.

-

-

Never rely on token return values alone

-

For critical flows, verify state transitions using balance deltas where appropriate (especially when supporting fee-on-transfer behavior).

-

-

Normalize token handling across router + pool

-

If router uses safe wrappers but pool uses raw calls, you’ve created an inconsistent trust surface.

-

Practical rule: “Token transfer correctness is part of protocol correctness.” Don’t get to outsource it to token authors.

Permit Support (EIP-2612) for One-Click Approve + Swap

Approvals are UX friction and also a security vector (users granting unlimited allowances to routers they don’t understand). Enterprise DEX UX typically requires a permit pathway so users can:

-

sign a message (off-chain)

-

execute approve + swap in one transaction (on-chain)

Key realities:

-

Not all tokens support EIP-2612

Must support both:-

Permit path when available

-

Standard

approvewhen not

-

-

Permit handling must be nonce-safe

Permit signatures depend on token nonces and deadlines. System router must:-

validate deadline

-

submit permit before swap execution

-

revert if permit fails (unless explicitly support “tryPermit then fallback”)

-

-

Router is the correct layer for permit

Pools should not manage user allowances. Router should:-

obtain permission (permit/approve)

-

move tokens into pool

-

execute swap

-

Enterprise pattern:

-

permit + exactInputSwapas a single atomic operation -

strict replay protection via nonce consumption

-

minimal allowance scope (don’t force infinite approval patterns)

Done correctly, permit reduces approval attacks and dramatically improves conversion in production.

Re-Entrancy Protections (Pool/Router Must Be Adversarial-Execution Safe)

A DEX is a perfect target for reentrancy because it:

-

moves tokens

-

updates pricing state

-

interacts with external token contracts

-

may call user-controlled callbacks (v3-like designs)

Must assume any external call can re-enter if there exists a path.

Where reentrancy risk actually comes from:

-

token contracts (ERC777-style hooks, malicious tokens, callback behaviors)

-

pool callbacks (v3 swap callback patterns, flash swap patterns)

-

router multicalls (composed execution paths)

Enterprise-grade protections include:

-

Reentrancy guards at the right granularity

-

Pools: protect swap/mint/burn/collect paths (anything that changes state + transfers)

-

Router: protect multi-step flows so intermediate states cannot be exploited

-

-

Checks-effects-interactions discipline

-

Update state first, then transfer, unless the math requires balance-first validation (then use locked state flags)

-

-

Explicit callback authorization

If design includes callbacks (like Uniswap v3), enforce:-

callback must come from the exact expected pool

-

callback caller must match computed pool address

-

callback must deliver exact required amounts before continuing

-

Important: “Solidity 0.8 safe math” does not protect you from reentrancy. These are separate domains.

Handling Fee-on-Transfer Tokens (Decide Explicitly: Support or Disallow)

Fee-on-transfer tokens break a fundamental AMM assumption:

the amount sent equals the amount received.

This impacts:

-

swap pricing correctness

-

invariant enforcement

-

router quoting accuracy

-

multi-hop execution reliability

-

slippage guarantees

Must decide one of two strategies.

Option 1: Disallow fee-on-transfer tokens (recommended for correctness)

This is the cleanest enterprise stance. Explicitly reject tokens that do not preserve transfer amounts, because they degrade guarantees for all users.

How this is enforced:

-

maintain denylist patterns or configuration at pool creation

-

or validate that

balanceAfter - balanceBefore == expectedInin critical flows and revert otherwise

This approach keeps invariant logic pure and quoting accurate.

Option 2: Support them with specialized logic (only if DEX is designed for it)

If support them, must treat swaps as balance-delta based, not calldata based.

Meaning:

-

Measure actual received input in the pool

-

compute output based on that real input

-

accept that “exact input” becomes less predictable

-

redesign quoting and UI to reflect fee behavior

This adds complexity across the entire stack:

-

routers must simulate token fees (often impossible reliably)

-

users must tolerate less deterministic minimum outputs

-

multi-hop paths become fragile (each hop may fee-tax)

Enterprise reality: most serious AMMs either disallow these tokens or isolate them into separate pools with explicit risk labeling.

5) Price, Slippage, and Swap Math (DEX Correctness Layer)

In an AMM DEX, the math is not an implementation detail—it is the protocol. Every “swap” is just a state transition that must preserve invariant correctness under adversarial execution, rounding constraints, token quirks, and MEV ordering. If this layer is wrong, nothing else matters: routers route incorrectly, quotes lie, LPs are mispaid, and attackers extract value directly from invariant drift.

A production DEX treats the math layer as a correctness boundary with explicit guarantees:

-

swaps must obey the invariant within defined rounding rules

-

fees must be applied deterministically

-

slippage protection must be enforceable on-chain

-

routing must reflect executable reality, not theoretical optimality

There are two dominant AMM math models in modern DeFi: constant product (v2-style) and concentrated liquidity (v3-style). Everything else is a variant.

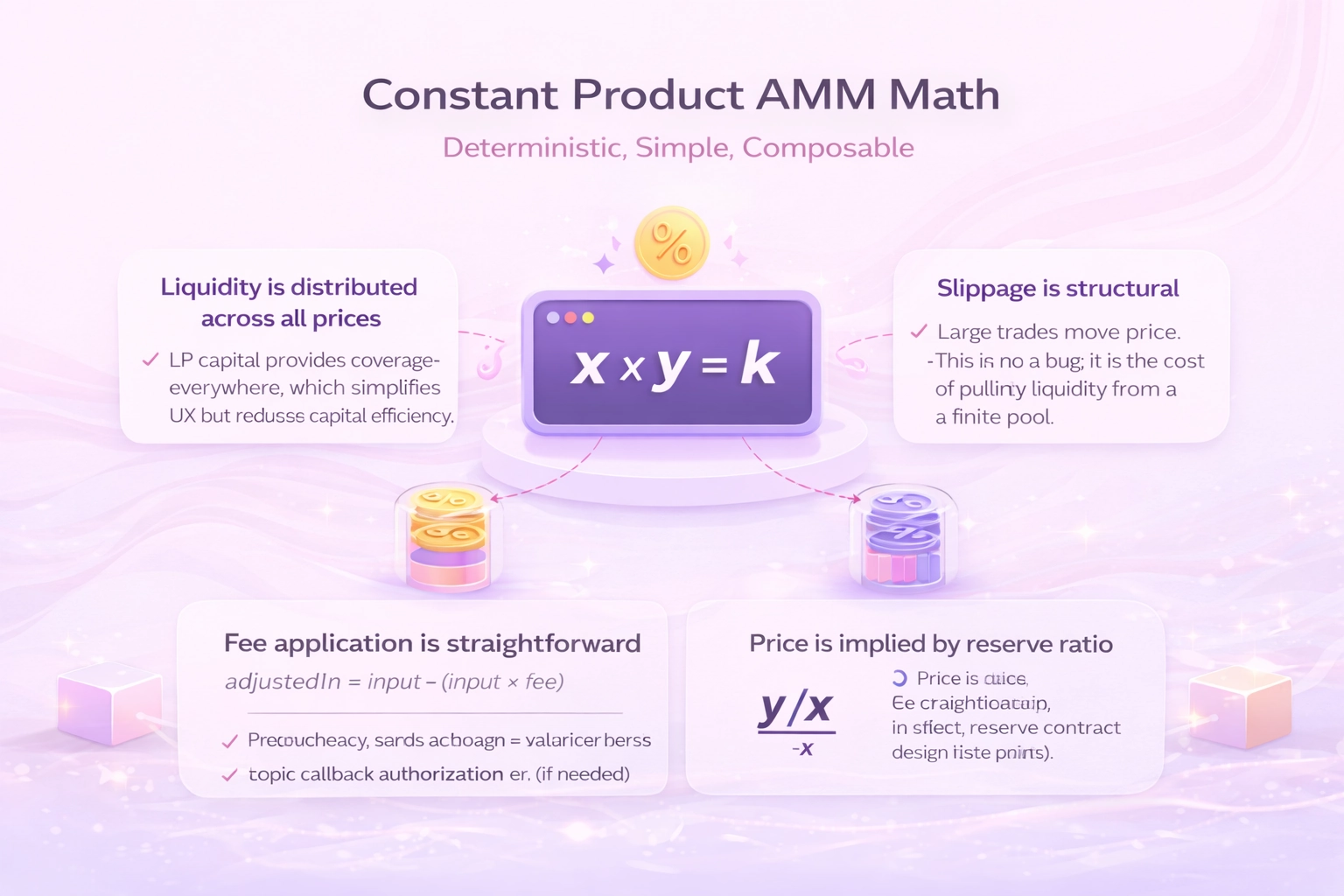

v2 Constant Product (x * y = k): Deterministic, Simple, Composable

The v2-style AMM uses a constant-product invariant: reserves maintain x * y = k (adjusted for fees). A swap is executed by increasing one reserve and decreasing the other such that the post-swap reserves satisfy the invariant.

data-start=”1258″ data-end=”1350″>What matters in production is not the formula itself, but the operational truths it creates:

-

Liquidity is distributed across all prices

LP capital provides coverage everywhere, which simplifies UX but reduces capital efficiency. -

Price is implied by reserve ratio

Spot price is approximatelyy/x(for token0/token1 direction), meaning price shifts immediately with trade size. -

Slippage is structural

Large trades move price. This is not a bug; it is the cost of pulling liquidity from a finite pool. -

Fee application is straightforward

The input amount is fee-adjusted before applying the invariant. This directly rewards LPs through reserve growth.

PancakeSwap’s early AMM behavior is v2-style logic simple pool creation, predictable swap execution, and easy LP token accounting. The result is fast bootstrapping and broad composability.

v3 Concentrated Liquidity: Tick Math + Liquidity Ranges + Fee Growth Accounting

Concentrated liquidity transforms AMMs from “one pool covers all prices” into “liquidity is placed across chosen price ranges.” This improves capital efficiency and allows professional market-making behaviors on-chain, but it dramatically increases the math and accounting surface.

Core correctness elements must get right:

-

Ticks define discrete price boundaries

Price moves across ticks; each tick has state that determines how liquidity changes when crossed. -

Liquidity is piecewise, not global

At any moment, “active liquidity” is only the liquidity allocated in the current price range. This means price impact depends on local liquidity depth, not total TVL. -

Swap math is incremental

A single swap may traverse multiple ticks. Output is computed segment-by-segment as price moves, applying fees and updating tick state. -

Fee growth is tracked per liquidity unit

Fees are not just “in reserves.” They are accumulated as fee growth variables and claimed per position based on snapshots. This is ledger-style accounting and must be invariant-safe under rounding.

Uniswap v3’s execution model is exactly this—ticks, active liquidity, and per-position fee entitlement. It’s the reason v3 can provide tighter pricing with less idle capital, but also why LP UX requires range management.

Slippage Protection (On-Chain Intent Enforcement)

Slippage controls are not optional UX helpers; they are protocol’s user-intent guardrails. Without them, the chain’s ordering environment (especially on public mempools) turns every trade into an MEV target.

Enterprise-grade slippage protection includes:

-

amountOutMin/amountInMaxenforcement (v2/v3 routers)

The router must revert unless the realized execution respects the user’s signed slippage bounds. This converts “quote” into an enforceable constraint. -

Deadline enforcement

Every swap should include a deadline. This prevents stale quotes from executing after market conditions have changed or after the transaction was intentionally delayed. -

sqrtPriceLimitX96-style price limits (v3-like)

This is a stronger guard thanamountOutMinalone because it caps how far the pool price is allowed to move during execution. It helps protect against pathological execution paths and can reduce certain sandwich shapes.

On AMMs like Uniswap-style pools, a user who sets loose slippage effectively pre-approves extraction. Proper slippage bounds are the difference between “trade executed” and “trade executed safely.”

Price Impact Estimation (Front-End Truth + Router Reality)

Users do not experience “invariant math.” They experience price impact. Enterprise DEX UX must compute and show price impact using the same logic that execution will use, or it creates a trust gap and increases failed transactions.

A robust approach:

-

Front-end estimation for UX

-

compute expected output from current pool state

-

compute price impact relative to mid-price or reference price

-

display impact + minimum received at chosen slippage

-

-

Router-side enforceable checks

-

regardless of UI estimates, the router enforces

amountOutMin, deadlines, and (if v3) price limits -

the router must treat UI as advisory, not authoritative

-

Important nuance: price impact must consider the actual route (multi-hop), not just the first pool. A small impact per hop can compound into a large end-to-end impact.

Multi-Hop Routing Logic

Routing is math under constraints. The theoretical “best route” is irrelevant if it cannot execute within gas/compute limits, if intermediate pools are illiquid, or if the route is MEV-fragile.

Production routing logic typically includes:

-

Path discovery

-

identify candidate pools across fee tiers and pairs

-

prune by liquidity depth and historical reliability

-

-

Quote simulation

-

simulate per-hop outputs using current on-chain state

-

aggregate total output, fees paid, and estimated gas

-

-

Execution-safe route selection

-

choose routes that minimize failure probability, not just maximize output

-

apply caps on hop count and pool count to remain executable

-

-

Atomic execution

-

the router executes all hops in one transaction

-

if any hop fails or slippage bounds are violated, the entire swap reverts

-

Uniswap routers and many aggregators follow this split—quoting/simulation off-chain, execution on-chain. The router is not an optimizer; it is the enforcement and orchestration layer.

6) Liquidity Flow (Add / Remove)

Liquidity flow is where capital enters and exits the AMM, and it is one of the easiest places to introduce silent accounting bugs. Unlike swaps, which are short-lived and user-facing, liquidity positions can remain open for months. Any mistake here compounds over time and eventually manifests as missing funds, incorrect fee claims, or broken pool invariants.

Enterprise-grade DEX design treats liquidity flow as a stateful financial lifecycle, not a one-off transaction. The protocol must define exactly how liquidity is valued, how ownership is represented, how fees accrue, and how capital is returned—under both normal and adversarial conditions.

Add Liquidity (Capital Admission Into the Pool)

Adding liquidity is the act of converting user-owned tokens into protocol-governed liquidity units. This must be deterministic and invariant-preserving.

The add flow begins with pair and amount validation:

-

Pair validation

The pool must already exist or be created via the Factory. Token ordering is enforced (token0 < token1) so accounting remains consistent across all contracts. -

Amount validation

-

v2-style pools require proportional deposits relative to current reserves.

-

v3-style positions require amounts consistent with the chosen price range.

Any excess tokens are either rejected or returned, depending on design.

-

In a Uniswap v2–style pool, if the pool ratio is 1 ETH : 2,000 USDC, depositing 1 ETH and 1,000 USDC would result in partial usage and a refund, or a revert, depending on router behavior. The protocol must define this clearly.

Minting Liquidity Representation (Ownership Encoding)

Once amounts are validated, the protocol mints a representation of liquidity ownership.

v2-style: LP token minting

-

LP tokens represent proportional ownership

The number of LP tokens minted reflects the depositor’s share of total pool liquidity. -

Invariant alignment

Minting must preserve the invariant and accurately reflect pool state before and after deposit. -

Fee alignment

LP tokens implicitly entitle holders to future fees via reserve growth.

This model is simple, composable, and widely understood—one reason why PancakeSwap-style pools scaled quickly in retail environments.

v3-style: NFT position minting

-

Positions are discrete, not proportional

Each NFT encodes:-

price range

-

liquidity amount

-

fee growth snapshot at mint time

-

-

Capital is range-bound

Liquidity only participates in swaps when price is within the chosen range. -

Fee accounting is explicit

Fees are not “in the pool”; they are tracked and claimable per position.

In Uniswap v3, two LPs in the same pool but different ranges earn fees very differently, even with equal capital. This is intentional and must be reflected exactly in contract accounting.

Recording Fee Accounting State (Critical for Correct Withdrawals)

At liquidity entry time, the protocol must snapshot fee-related state so that future claims can be computed correctly.

-

v2-style

Fees are implicitly tracked via reserve growth. No per-position snapshot is required, but invariant math must be exact to avoid dilution. -

v3-style

Fee growth variables (global and per-tick) are snapshotted into the position. This snapshot defines what fees belong to the LP vs what accrued before entry.

This step is invisible to users but essential for correctness. If fee state is recorded incorrectly at entry, all future claims become wrong.

Remove Liquidity (Capital Exit From the Pool)

Removing liquidity is the inverse lifecycle operation. It converts protocol-governed liquidity units back into user-owned tokens.

The remove flow consists of:

-

Ownership validation

-

v2: user must hold LP tokens

-

v3: user must own the NFT position

-

-

Liquidity burn / decrease

-

v2: LP tokens are burned, reducing total supply

-

v3: liquidity is decreased for the specific position (partial or full)

-

-

Underlying token calculation

The protocol computes the exact token amounts owed based on:-

current pool state

-

position share or active liquidity

-

accumulated fees (if included)

-

-

Token return

Tokens are transferred back to the user using safe transfer logic.

Removing liquidity from a Bancor-style or Uniswap-style pool returns tokens at the current pool price, not the entry price. Impermanent loss is a property of this exit, not a bug.

Fee Claiming (If Separated From Liquidity Removal)

Some designs separate liquidity withdrawal from fee collection to allow LPs to:

-

keep capital deployed

-

periodically harvest fees

In such designs:

-

Fee claim must not modify principal

Claiming fees should not change the liquidity amount or price range. -

Fee calculation must be idempotent

Multiple claims without intervening swaps should result in zero additional payout. -

Fee state must update atomically

After a claim, the position’s fee snapshot must be updated to prevent double-claims.

Uniswap v3’s collect flow is a canonical example of explicit, per-position fee harvesting.

Edge Cases Must Handle Explicitly

Initial Pool Bootstrap

The first liquidity provider defines the initial price. This is a privileged and risky moment.

-

No ratio enforcement exists yet

The protocol cannot infer a “correct” price; it accepts what is provided. -

Minimum liquidity lock is applied (v2-style)

A small amount of LP tokens is permanently locked to prevent division-by-zero and price manipulation via total liquidity burn. -

Subsequent LPs inherit this price

Any mispricing here becomes an arbitrage opportunity, not a protocol bug.

Early Uniswap pools rely on arbitrage to correct initial price misalignment after bootstrap.

Imbalanced Adds (Capital Efficiency vs UX Trade-off)

Imbalanced adds occur when a user supplies token amounts not matching the pool’s ratio.

Protocol choices include:

-

Strict proportional enforcement

Revert unless exact ratio is met. Maximizes invariant purity, worsens UX. -

Partial acceptance with refunds

Accept only what fits the ratio and return excess. Improves UX, adds complexity. -

Range-based acceptance (v3-style)

Liquidity is accepted only where the price range allows, implicitly handling imbalance.

Whatever path choose, it must be consistent across router, pool, and UI expectations.

Minimum Liquidity Lock (v2-Style Safety Mechanism)

Minimum liquidity locks serve two purposes:

-

Prevent total liquidity from ever reaching zero

Avoids division-by-zero errors and undefined pricing. -

Discourage pool griefing

Prevents attackers from fully draining and reinitializing pools at manipulated prices.

This locked liquidity is not a fee; it is a structural safeguard. Enterprise DEXs treat it as non-negotiable for v2-style designs.

7) Off-Chain Indexing (Required for Real UX)

A DEX that relies only on on-chain reads is not usable at scale. Blockchains are execution engines, not query engines. While they guarantee correctness and immutability, they do not support historical queries, aggregations, sorting, or fast discovery. Without an off-chain indexing layer, even a perfectly designed AMM becomes opaque, slow, and unusable for real users.

Enterprise-grade DEX architecture therefore treats off-chain indexing as a first-class system component, not an auxiliary service. It is the bridge between deterministic on-chain state and human-usable interfaces.

Why On-Chain Data Alone Is Insufficient

On-chain events are append-only logs. They cannot answer questions like:

-

“What are all pools sorted by TVL?”

-

“What swaps did this user make last month?”

-

“Which pools have the highest fee APR right now?”

-

“What liquidity positions does this wallet currently own?”

Answering these questions directly from RPC calls would require scanning entire block histories repeatedly, which is neither fast nor economically viable.

As a result, every production DEX builds an indexer that converts raw events into structured, queryable data.

The Indexer (Read Model)

The indexer is a system that:

-

listens to on-chain events emitted by contracts

-

transforms them into normalized entities

-

stores them in a database optimized for reads and aggregations

Common production approaches include:

-

The Graph for declarative indexing and hosted/subgraph deployments

-

Custom indexers using RPC + database pipelines for full control

-

Substreams for high-throughput, deterministic streaming at scale

The choice depends on scale, latency requirements, and operational control, but the architectural role is the same: create a reliable read model of the DEX.

Core Data Must Index

An enterprise DEX indexer does not mirror chain state blindly; it builds domain-specific projections.

Pools List

Pools are the primary market objects.

-

pool address, tokens, fee tier

-

creation block and timestamp

-

current liquidity state snapshot

This enables pool discovery, validation, and canonical routing.

Uniswap-style UIs rely on indexed pool registries rather than querying the Factory on every page load.

Swaps, Mints, and Burns

These events define economic activity.

-

Swaps

-

input/output tokens and amounts

-

price at execution

-

trader address

-

fees paid

-

-

Mints / Burns

-

liquidity added or removed

-

position identifiers (LP token or NFT)

-

These records power trade history, volume analytics, and fee calculations.

TVL, Volume, and Fees (Derived Metrics)

Raw events are not enough. System must compute derived metrics:

-

TVL

Aggregated pool balances valued consistently (often via reference pricing). -

Volume

Rolling and cumulative swap volume per pool, per token, per time window. -

Fees

Fees generated per pool and attributed to LPs or protocol treasury.

These metrics are recalculated incrementally as events stream in and are what users actually consume.

User Positions

Positions are long-lived relationships between users and pools.

-

v2-style: LP token balances per wallet

-

v3-style: NFT positions with range, liquidity, and fee state

The indexer must maintain:

-

current active positions

-

historical changes (adds, removes, claims)

-

unrealized vs realized fee data

Without this, a “Positions” dashboard is impossible.

What Off-Chain Indexing Powers

Once indexed, this data becomes the backbone of the entire DEX experience.

Charts and Pool Pages

-

price charts (spot, TWAP, historical)

-

liquidity depth visualizations

-

volume and fee APR graphs

These are computed entirely from indexed data, not live chain calls.

PancakeSwap and Uniswap analytics pages are indexer-driven systems, not on-chain queries.

Position Dashboards

LPs need to see:

-

where their capital is deployed

-

current value vs entry value

-

fees earned and claimable

-

performance over time

This requires combining on-chain events with off-chain aggregation logic.

Routing Discovery

Routers and quote services depend on indexed data to:

-

discover existing pools

-

estimate liquidity depth

-

prune illiquid or inactive paths

Without indexed pool and liquidity data, routing would be slow, inaccurate, or impossible.

Analytics and Leaderboards

Advanced features such as:

-

top pools by volume

-

top traders or LPs

-

fee generation rankings

-

protocol growth metrics

are purely indexer products. They are not derivable in real time from chain state.

Indexer Design Constraints (Production Reality)

A mature DEX indexer must handle:

-

Chain reorgs

Events may be reverted. The indexer must roll back and re-apply deterministically. -

Event ordering guarantees

Swaps, mints, and burns must be processed in exact block and transaction order. -

Data consistency

Derived metrics must remain correct across restarts and partial failures. -

Latency vs correctness trade-offs

Fast updates are important, but correctness always wins in financial systems.

Enterprise systems treat the indexer as critical infrastructure, with monitoring, backups, and reconciliation processes.

Off-Chain Indexing as a Contract With Users

From a user’s perspective, the indexer is the DEX. If charts are wrong, balances are missing, or positions don’t appear, trust is lost—even if the on-chain contracts are correct.

That’s why production DEX architecture treats off-chain indexing as:

-

a deterministic extension of on-chain state

-

a read-optimized financial ledger

-

a UX-critical system, not an optional add-on

8) Routing + Quoting Service (Fast Swaps Need This)

A DEX can be mathematically correct and still feel broken if quotes are slow or unreliable. Users do not think in invariants—they think in “How much will I receive?” and “Will this transaction fail?” That expectation forces every production AMM DEX to build a dedicated quoting and routing layer that sits between raw on-chain pools and the frontend.

This is not just a performance optimization. It is a correctness product: the quote system defines what users believe will happen, and the execution system must enforce what actually happens. If these two diverge, get failed swaps, user distrust, and exploitable gaps.

Why Need a Quote API Even With On-Chain Pools

On-chain pools can provide state, but they cannot provide a user-grade quote experience because:

-

reading multiple pools over RPC is slow and inconsistent under load

-

discovering optimal routes requires graph search and simulation

-

route computation is compute-heavy and not suitable for frontends

-

gas estimation is chain-dependent and changes dynamically

So centralize this into a Quote API that produces fast, deterministic, execution-aligned outputs.

In Uniswap-style ecosystems, even if the router can execute swaps trustlessly, most users still rely on an off-chain quoting layer to compute the best path and predict price impact before signing.

Quote API Responsibilities (What It Must Do)

A production Quote API does three jobs: state acquisition, route optimization, and execution-aligned output construction.

1) Read On-Chain State (RPC)

The Quote API is a client of the chain. It must fetch:

-

pool reserves / liquidity state

-

fee tiers and pool configs

-

current price state (v2 reserves ratio, v3 sqrtPrice/tick/liquidity)

-

token metadata (decimals, symbol) if not cached

-

block context (latest block, base fee, gas pricing inputs)

Key requirement: Quote API must be reorg-aware and block-consistent. Quotes computed from mixed block states produce phantom outputs.

2) Compute Best Route Across Pools

Routing is a graph problem under execution constraints. The Quote API must:

-

build a pool graph from indexer discovery (pools + liquidity)

-

generate candidate paths (direct, 2-hop, limited 3-hop)

-

simulate output for each candidate path

-

choose the best route by objective function

The objective function is rarely “max output only.” Mature routers consider:

-

output amount

-

price impact

-

gas cost

-

failure probability (illiquid hops, volatile pools)

-

hop count limits (execution budget reality)

A multi-hop route might yield 0.2% more output, but if it adds one more hop on a high-fee chain, net execution value becomes worse. Enterprise routers optimize for net outcome, not theoretical output.

3) Return Execution-Ready Quote Data

The Quote API should return not only “expected out,” but the full execution contract with the user.

A standard response includes:

-

expected out

The predicted output based on current state and simulated execution. -

price impact

A user-facing measure of how much the trade moves price due to liquidity depth. -

min received at slippage

Derived from user slippage tolerance and expected output: this becomesamountOutMin. -

gas estimate

Estimated gas units + fee cost estimate. This is critical for UX and route ranking. -

route steps

Concrete hop-by-hop path: pool addresses, token in/out sequence, fee tiers, and call parameters.

This output must be stable enough that the frontend can render it, and deterministic enough that the router can execute it without surprises.

Quoter vs Router (Separation of Concerns)

Production AMM stacks split quoting and execution into distinct roles.

Quoter (Simulation / callStatic)

The Quoter is responsible for simulation. It answers:

-

if I execute this exact path, what output will I get?

-

what will the price become after execution?

-

what ticks will be crossed (v3-like)?

-

what are the exact per-hop amounts?

Implementation patterns:

-

Off-chain simulation using on-chain state

Use the pool math logic in a backend service. -

callStatic / read-only contract simulation

A Quoter contract can be called in a read-only way to simulate execution without state changes.

The critical property: quoting must match execution semantics. If off-chain math differs from pool math (rounding, fee application, tick crossing), Quote API becomes a source of failed swaps.

Uniswap v3 introduced dedicated quoter patterns because v3 swap outcomes cannot be approximated reliably without simulating tick traversal.

Router (Real Execution)

The Router is responsible for execution. It enforces user intent:

-

executes the route steps returned by the Quote API

-

applies slippage constraints (

amountOutMin, deadlines) -

ensures atomicity across hops

-

reverts if the execution does not match user constraints

Important boundary:

-

Quoter can be wrong; Router must still be safe.

That is why the Router’s slippage and deadline checks are non-negotiable.

Operational Constraints (What Makes Quotes Production-Grade)

A Quote API must be engineered like a high-availability trading service.

Key production constraints:

-

Latency targets

Quotes must feel instant. That requires caching pool state, parallel RPC calls, and aggressive pruning of route candidates. -

Consistency

Quotes should be computed from a single block context. Mixing blocks creates phantom routing. -

Fallback strategy

If RPC is degraded, the system should degrade gracefully:-

fewer route candidates

-

fallback to direct pools

-

conservative gas estimates

-

or temporary disablement rather than wrong quotes

-

-

MEV-aware quoting

Quotes should reflect that public mempools are adversarial. The system must guide users into safe slippage bounds and optionally recommend protected submission paths.

Routing + Quoting as the “DEX Performance Layer”

On-chain contracts define correctness, but quoting and routing define usability.

A modern AMM DEX is judged by:

-

how fast and accurate its quotes are

-

how often swaps succeed under real conditions

-

how well routes handle liquidity fragmentation

-

how reliably gas and impact are predicted

This is why the Quote API is not an accessory,it is the DEX’s real-time execution intelligence.

9) Oracles (Only If DEX Uses External Price)

A pure AMM DEX does not inherently require oracles. If protocol only facilitates swaps using internal pool pricing, the AMM itself is the price source. Introducing oracles in that case does not improve correctness—it often increases attack surface.

However, the moment DEX begins to reason about “fair price”, external value, or time, oracles become a structural dependency. At that point, oracle design is no longer optional infrastructure; it becomes part of protocol’s security model.

Enterprise-grade DEXs are explicit about when and why they cross this boundary.

When a DEX Can Operate Without Oracles

If DEX:

-

executes swaps strictly against internal pool state

-

applies fixed, deterministic fees

-

does not attempt to judge whether a price is “correct”

-

does not reference off-pool markets

then the AMM itself is sufficient. The pool price may be manipulated temporarily, but that manipulation is economically constrained by liquidity depth and arbitrage, not by oracle correctness.

Early Uniswap-style spot swaps work without any external oracle because they never ask, “Is this price valid?” They simply execute against the pool.

When Oracles Become Mandatory

The moment protocol needs to compare, stabilize, or protect prices, oracles are unavoidable.

Stable Swap Pegs and Dynamic Fees

Stable or quasi-stable pools require price awareness beyond instantaneous pool ratios.

-

Maintaining a peg (e.g., stable-to-stable swaps) requires knowing when the pool deviates from reference value.

-

Dynamic fee models require understanding volatility or deviation over time.

Without an oracle, the protocol cannot distinguish between organic price movement and manipulation.

Lending Integrations

If DEX integrates or feeds data into lending protocols, price integrity becomes critical.

-

Collateral valuation cannot rely on a manipulable spot price.

-

Short-lived price distortions can trigger liquidations or bad debt.

Lending protocols integrating Uniswap-style pools rely on time-weighted or externally validated prices rather than spot reserves.

Perpetuals and Derivatives

Perps, options, and structured products require mark price, index price, and funding rate calculations.

-

Spot AMM prices are too volatile and easily influenced for these purposes.

-

Oracle latency and smoothing become first-order risk parameters.

This is why derivative DEXs treat oracle architecture as core protocol logic, not auxiliary data.

Anti-Manipulation Checks

Even in spot AMMs, some protocols introduce guardrails:

-

prevent swaps far outside reference price

-

limit trade size relative to liquidity

-

detect abnormal price movement

All of these require an external or time-averaged reference.

Oracle Design Constraints (What Makes Oracles Safe in DEX Context)

Oracles do not make a DEX safer by default. Poor oracle design is often more dangerous than no oracle at all.

Key constraints enterprise systems enforce:

-

No single price source

Single-oracle reliance creates a single point of failure or manipulation. -

Explicit latency assumptions

Every oracle has update frequency and delay. Protocol must define acceptable staleness and behavior when data is delayed. -

Clear failure behavior

If oracle data is missing, stale, or inconsistent, the protocol must define what happens:-

pause affected actions

-

fall back to internal pricing

-

restrict trade sizes

Undefined behavior is an exploit vector.

-

The Hybrid Safety Model (TWAP + External Reference)

The most common and battle-tested oracle architecture in AMM DEXs is a hybrid model.

Pool TWAP (Time-Weighted Average Price)

-

Derived from on-chain pool state over time.

-

Resistant to single-block manipulation.

-

Cheap to compute once infrastructure is in place.

However:

-

TWAP lags fast-moving markets.

-

Low-liquidity pools still produce weak signals.

External Oracle Reference (e.g., Chainlink)

-

Aggregates prices from multiple sources.

-

Independent of pool liquidity.

-

Designed with redundancy and monitoring.

However:

-

Updates are discrete, not continuous.

-

Can lag during volatility spikes.

-

Becomes a dependency on external infrastructure.

Why Hybrid Works

Combining both allows to:

-

detect divergence between pool price and external reference

-

bound acceptable price ranges

-

apply safety checks only when deviation exceeds defined thresholds

Many modern AMM-based systems use internal TWAP as the primary signal and external feeds as a sanity check rather than a constant authority.

Where Oracle Logic Should Live

Oracle consumption should be:

-

Isolated from swap execution

Swaps should not depend on oracle freshness unless explicitly designed to. -

Used for guards, not price setting

Oracles should inform limits, fees, or risk controls—not replace AMM pricing. -

Upgradeable only via governance

Oracle parameters are risk parameters. Changes must be slow, transparent, and governed.

Embedding oracle calls directly inside hot swap paths is a common anti-pattern. It increases gas cost, introduces external failure risk, and complicates execution guarantees.

Oracle Risk Is Protocol Risk

Once oracles are introduced, DEX’s security is no longer purely economic—it becomes informational.

That means:

-

oracle failure can halt the protocol

-

stale data can cause mass loss

-

manipulation can bypass otherwise correct AMM math

Enterprise-grade DEXs therefore treat oracle architecture with the same rigor as pool math and liquidity accounting.

10) Security Architecture (Non-Negotiable)

Security in a DEX is not a checklist item added before launch; it is an architectural property enforced at every layer. Unlike traditional systems, there is no rollback, no customer support reversal, and no “hotfix after incident” path once funds are lost. Every weakness becomes an economic opportunity for an adversary.

Enterprise-grade DEXs assume hostile execution environments by default: adversarial mempools, malicious tokens, rational MEV actors, and users who will push edge cases unintentionally. The security architecture exists to make all of that survivable.

This section defines the minimum security posture required before mainnet.

Reentrancy Guard (State Integrity First)

Reentrancy is not an exotic exploit; it is a consequence of external calls combined with mutable state. Any DEX that transfers tokens and updates balances is exposed unless explicitly protected.

Production-grade principles:

-

Every function that mutates critical state and performs external calls must be guarded

This includes swap, mint, burn, collect, and router execution paths. -

Guard at the correct boundary

Pools protect invariant state. Routers protect multi-step orchestration. Do not assume one layer protects the other. -

Callbacks must be strictly authorized

If design uses callbacks (v3-style swaps, flash interactions), enforce:-

exact caller validation

-

exact owed amount verification

-

single-entry execution paths

-

Most historical AMM exploits that weren’t math-related were reentrancy or callback abuse incidents.

Overflow-Safe Math (Necessary but Not Sufficient)

Solidity 0.8+ introduces checked arithmetic, but safe math is broader than overflow protection.

What still requires discipline:

-

Rounding direction must be intentional

Fee calculations, liquidity shares, and invariant math must always round in the protocol’s favor (never the trader’s) to avoid invariant leakage. -

Intermediate value bounds

Tick math, price square roots, and multiplication-heavy formulas can still overflow intermediate variables if not bounded. -

Consistency across simulation and execution

Off-chain quoter math must match on-chain rounding exactly. A one-unit mismatch becomes a revert or exploit path.

Overflow protection prevents crashes; it does not guarantee economic correctness.

Token Ordering and Pool Uniqueness (Canonical State)

Fragmentation is a silent failure mode. If multiple pools can exist for the same token pair under ambiguous rules, routing becomes unsafe and liquidity becomes diluted.

Security requirements:

-

Canonical token ordering

Always enforce a deterministic order (token0 < token1) at pool creation and execution. -

Strict pool uniqueness

(tokenA, tokenB, feeTier)must map to exactly one pool address. -

Factory as single source of truth

Routers, indexers, and UIs must rely on Factory state, not heuristics.

Uniswap-style Factory registries exist primarily to prevent malicious or duplicate pool injection into routing paths.

Slippage and Deadline Enforcement (User Intent Protection)

Slippage controls are a security boundary, not a UX preference.

Why they matter:

-

Public mempools are adversarial

Any transaction without slippage bounds is a pre-approved loss envelope. -

Delayed inclusion is normal

Transactions can be mined later than expected, under different price conditions.

Minimum enforcement requirements:

-

amountOutMin/amountInMaxchecks

Must be enforced in the Router, not just estimated in the UI. -

Deadline checks

Every execution path should revert if executed after the user-defined time window. -

Price limits where applicable (v3-style)

Prevents extreme price movement within a single swap.

If execution violates user intent, the transaction must revert—silently “filling at worse price” is a security failure.

Admin Rights Minimization (Trust Surface Control)

Admin privileges are the largest non-code risk in a DEX.

Enterprise posture:

-

No admin access to user funds

Ever. Any mechanism that allows this collapses the trust model. -

Timelock all sensitive operations

Fee switches, parameter changes, oracle updates, and pause actions must go through a delay. -

Multisig over single-key control

Admin actions require quorum, not individual discretion. -

Explicitly document admin scope

Users and auditors should be able to answer: What can governance do, and what can it never do?

Mature protocols treat governance like slow, observable configuration—not a live control panel.

Pause Switches (Only If Necessary, and Scoped)

Pause functionality is controversial but sometimes justified.

If included, it must follow strict rules:

-

Pause scope must be minimal

For example:-

pause new pool creation

-

pause specific router functions

Not “pause everything and seize funds.”

-

-

Pause must be reversible and observable

On-chain events, clear state flags, and governance-controlled unpause. -

Pause should never hide failure

Pausing does not fix bugs; it buys time to respond.

Overpowered pause switches are indistinguishable from custodial control.

MEV Considerations (Cannot Eliminate, Only Manage)

MEV is not an attack; it is a property of transparent execution. Security architecture must assume it exists.

Sandwich Resistance (Hard, Never Perfect)

AMMs inherently expose trades to sandwiching.

What can do:

-

enforce tight slippage defaults

-

support price limits (v3-style)

-

educate users on risk boundaries

What cannot do:

-

eliminate sandwiching entirely without changing execution model

Protocols that promise “MEV-free AMMs” without execution redesign are overselling.

Private Transaction Paths / MEV-Protected RPC

Providing optional MEV-protected submission paths improves user safety.

-

private RPC endpoints

-

block builder integration

-

wallet-level MEV protection recommendations

This does not change protocol logic, but it materially improves execution outcomes for large trades.

Fee and Slippage Guidance

Security includes preventing user self-harm.

-

dynamic slippage recommendations based on liquidity

-

warnings for high price impact trades

-

route suggestions that reduce exposure

These are not marketing features; they reduce exploitability.

Testing and Verification (Non-Optional)

Security architecture is incomplete without proof.

Unit Tests (Invariant Enforcement)

-

swap math correctness

-

fee application

-

liquidity mint/burn correctness

-

edge cases (zero liquidity, boundary values)

Fuzz Tests (Adversarial Exploration)

-

random trade sequences

-

random liquidity changes

-

invariant preservation under chaos

Tools like Foundry or Echidna are standard at this level.

Fork Tests (Reality Simulation)

-

test against real chain state

-

simulate MEV conditions

-

validate behavior under realistic liquidity and volatility

Independent Audit

Audits are not guarantees, but they are a baseline.

-

choose auditors with AMM experience

-

treat findings as design feedback, not compliance hurdles

-

re-audit after material changes

Security as a Continuous Property

Security does not end at mainnet deployment. It is enforced through:

-

conservative defaults

-

minimal trust assumptions

-

transparent governance

-

continuous monitoring and testing

A DEX that survives adversarial markets is not one with the most features—it is one with the fewest assumptions.

11) Frontend Architecture (How Users Actually Interact)

A DEX does not fail in audits alone—it fails when users misunderstand outcomes, sign transactions they don’t comprehend, or lose trust because the interface misrepresents execution reality. The frontend is therefore not a “UI layer”; it is the human-facing execution boundary of the protocol.

Enterprise-grade DEX frontends are designed around one principle:

never promise what the chain cannot guarantee, and never hide what the chain will enforce.

This section defines the frontend as a coordinated system that translates protocol constraints into clear, actionable user intent.

Wallet Connect Layer (Identity + Authority)

Wallet connection is how users authenticate, authorize, and assume responsibility for actions. A fragile wallet layer undermines everything else.

Production requirements:

-

Multi-wallet support

Support the dominant wallets of the target chain(s) without privileging a single provider. -

Network validation

Enforce correct chain selection. If the user is on the wrong network, block execution—not “best effort.” -

Permission clarity

Make approvals, permits, and signatures explicit. Users must know:-

what they are approving

-

whether approval is one-time or persistent

-

whether a permit is being used instead of approval

-

Mature Uniswap-style interfaces clearly separate “connect,” “approve,” and “swap,” reducing accidental over-approval.

Token List + Safety Checks (Asset Hygiene)

Tokens are the largest user-facing risk surface. The frontend must act as a filter, not a passive renderer.

Core responsibilities:

-

Canonical token lists

Use curated, versioned token lists. Avoid auto-importing arbitrary tokens without warning. -

Address-based identity

Display token address and chain, not just symbol. Symbols are not unique. -

Risk signaling

Flag tokens that are:-

newly deployed

-

low liquidity

-

fee-on-transfer

-

non-standard behavior (rebasing, restricted transfers)

-

-

Explicit user acknowledgment

If a user chooses to trade a risky or unknown token, require confirmation. This shifts responsibility transparently.

The frontend does not censor—it informs. Silence is a security failure.

Swap UI + Route Preview (Intent Visualization)

The swap interface is where user intent is formed. If this layer lies, execution correctness is irrelevant.

A production swap UI must show:

-

Quoted input/output

From the Quote API, not guessed locally. -

Route preview

-

tokens involved

-

pools or fee tiers used

-

hop count

-

This makes execution understandable, not opaque.

-

Price impact

Derived from the route and pool state. High impact must be highlighted, not hidden. -

Slippage control

User-adjustable, with safe defaults and warnings for extreme values.

Uniswap-style route previews and price impact warnings exist specifically to reduce user surprise during execution.

Liquidity UI (Capital Deployment Interface)

Liquidity provisioning is not trading—it is capital commitment. The frontend must reflect that difference.

Required elements:

-

Add liquidity flow

-

show required token ratios (v2-style)

-

show price range selection (v3-style)

-

preview minted LP tokens or position NFT

-

-

Risk communication

-

impermanent loss explanation

-

out-of-range behavior (v3)

-

fee earning expectations (non-guaranteed)

-

-

Clear outcomes

Users must know:-

what they receive (LP token / NFT)

-

what rights that represents

-

how to exit later

-

Liquidity UIs that feel “easy” but hide mechanics create long-term trust erosion.

Positions UI (Ownership + Performance)

Once capital is deployed, users care about state over time.

A production Positions UI shows:

-

Active positions

-

pool

-

liquidity amount

-

current value (estimate)

-

range status (in-range / out-of-range)

-

-

Fee accrual

-

earned

-

claimable

-

claimed historically

-

-

Position actions

-

add liquidity

-

remove liquidity

-

claim fees

-

This UI is powered entirely by indexed data and must remain consistent with on-chain reality.

Transaction State Tracking (Execution Transparency)

Blockchain execution is asynchronous and probabilistic. The frontend must reflect that honestly.

Transaction states to track and display:

-

Signature requested

-

Submitted to network

-

Pending / in mempool

-

Included in block

-

Confirmed / finalized

-

Failed / reverted

Critical rules:

-

Never show “success” before confirmation.

-

Always surface revert reasons when available.

-

Provide links to block explorers for verification.

Professional DEX UIs never hide failed transactions; they explain them.

Data Source Architecture (Separation of Truth)

A mature frontend does not rely on a single data source. It reconciles multiple layers of truth.

Quote API (Fast, Predictive)

-

Used for:

-

swap quotes

-

route previews

-

price impact

-

gas estimation

-

-

Optimized for speed and UX.

-

Treated as advisory, not authoritative.

Indexer (Historical, Aggregated)

-

Used for:

-

charts

-

TVL and volume

-

positions

-

analytics

-

-

Reorg-aware and eventually consistent.

-

Powers dashboards, not execution.

RPC (Final Verification)

-

Used for:

-

wallet balance checks

-

allowance validation

-

transaction confirmation

-

fallback correctness checks

-

-

Slow but authoritative.

-

The final arbiter of truth.

Enterprise frontends treat RPC as the ground truth, even when it disagrees with cached or indexed data.

Frontend as a Safety System

At scale, frontend architecture is not about aesthetics—it is about reducing accidental loss.

A correct frontend:

-

prevents impossible actions

-

communicates uncertainty honestly

-

enforces protocol constraints visually

-

aligns user expectation with execution reality

When users say “the DEX failed,” they are almost always describing a frontend failure, not a contract bug.

12) Deployment Plan (Step-by-Step)

Deployment is where a DEX stops being architecture and becomes a live economic system. The risk profile changes immediately: every misconfiguration becomes public, every deployment artifact becomes permanent, and every missing monitor becomes a delayed incident.