Key Takeaways: IoT Architecture Fundamentals

- IoT Architecture Fundamentals:

IoT architecture is end-to-end system design focused on data flow, failure handling, and scale—not static diagrams with boxes. - Edge vs Cloud Intelligence:

Modern IoT splits processing strategically—edge handles millisecond decisions, while cloud manages fleet-wide analytics and long-term storage. - Event-Driven Necessity:

IoT systems require asynchronous, event-driven architectures with message queues; synchronous request-response models collapse at scale. - Device Intelligence Trade-offs:

Dumb sensors reduce upfront cost but increase cloud load, while smart edge devices cut bandwidth by 90%+ and enable offline operation. - Gateway Critical Role:

Gateways are architectural boundaries that filter data, enforce security, buffer offline states, and enable local control loops. - Time-Series Data Architecture:

Traditional databases fail under billions of sensor events; purpose-built time-series systems with automatic aggregation are mandatory. - Scalability From Day One:

Architectures that work for 10 devices fail at 10,000—stateless services, horizontal scaling, and distributed systems are required upfront. - Failure Is the Default State:

IoT architecture must assume device, network, and service failure; graceful degradation prevents catastrophic production outages.

What “IoT Architecture” Actually Means

IoT architecture isn’t a diagram with boxes labeled “sensors,” “gateway,” “cloud,” and “dashboard.” That’s marketing collateral. Real IoT architecture is an end-to-end system design that answers: How does data flow from 10,000 sensors through unreliable networks to decision-making systems without losing critical information? How does the system handle a gateway going offline for three days? What happens when firmware updates fail on 15% of deployed devices?

Architecture defines the boundaries between components, the protocols they speak, the failure modes they tolerate, and the scalability limits before the system breaks. It’s the difference between a proof-of-concept that works with 10 devices and a production system managing 100,000.

IoT app development architecture and costs are directly determined by these foundational decisions. An architecture that assumes perfect connectivity will cost millions to fix when deployed to remote locations with spotty networks. An architecture designed for 100 devices will require complete rebuilding at 10,000. These aren’t hypothetical concerns—they’re production realities that separate successful IoT deployments from expensive failures.

Why IoT Application Architecture Is Fundamentally Different

Web applications assume reliable connectivity, stateless servers, and centralized processing. Mobile apps assume periodic connectivity and user-initiated actions. IoT systems operate under constraints that break these assumptions completely.

| Constraint | Web/Mobile Apps | IoT Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | Always online or user waits | Intermittent, unpredictable, unreliable |

| Power Source | Unlimited (plugged in or rechargeable) | Battery life: months to years |

| Processing Location | Centralized servers | Distributed: edge + cloud hybrid |

| Data Volume | User-generated, bounded | Continuous sensor streams, massive scale |

| Update Cadence | Deploy anytime, users update apps | Firmware updates to remote devices, can’t fail |

| Failure Impact | User inconvenience, retry later | Safety incidents, production downtime, inventory loss |

These constraints force architectural patterns that would be over-engineering in web apps but are essential in IoT: message queues for asynchronous processing, edge computing for real-time decisions, time-series databases for sensor data, and event-driven workflows instead of request-response patterns.

Core Architectural Responsibilities of an IoT System

IoT architecture must guarantee five non-negotiable properties. Systems that fail to deliver on any of these fail in production.

Reliability: System continues functioning despite device failures, network outages, and partial connectivity. A single gateway going offline shouldn’t bring down monitoring for 500 devices. Architecture must include redundancy, failover mechanisms, and graceful degradation.

Latency: Critical control loops execute within acceptable time bounds. Industrial safety systems need millisecond response times. Building automation can tolerate seconds. Healthcare monitoring falls somewhere in between. Architecture must place processing where latency requirements dictate—not where it’s convenient.

Security: Data and commands authenticated, encrypted, and authorized across trust boundaries. Every layer introduces attack surfaces. Architecture defines where security controls exist and how trust propagates through the system.

Scalability: Architecture supports 10x growth without fundamental redesign. What works for 100 devices must scale to 1,000 and eventually 10,000 without replacing core infrastructure. Horizontal scaling patterns must be baked into the architecture from day one.

Maintainability: Firmware updates, configuration changes, and debugging possible on deployed devices. Unlike web servers that can be updated in minutes, IoT devices might be physically inaccessible for months. Architecture must support remote management, staged rollouts, and rollback capabilities.

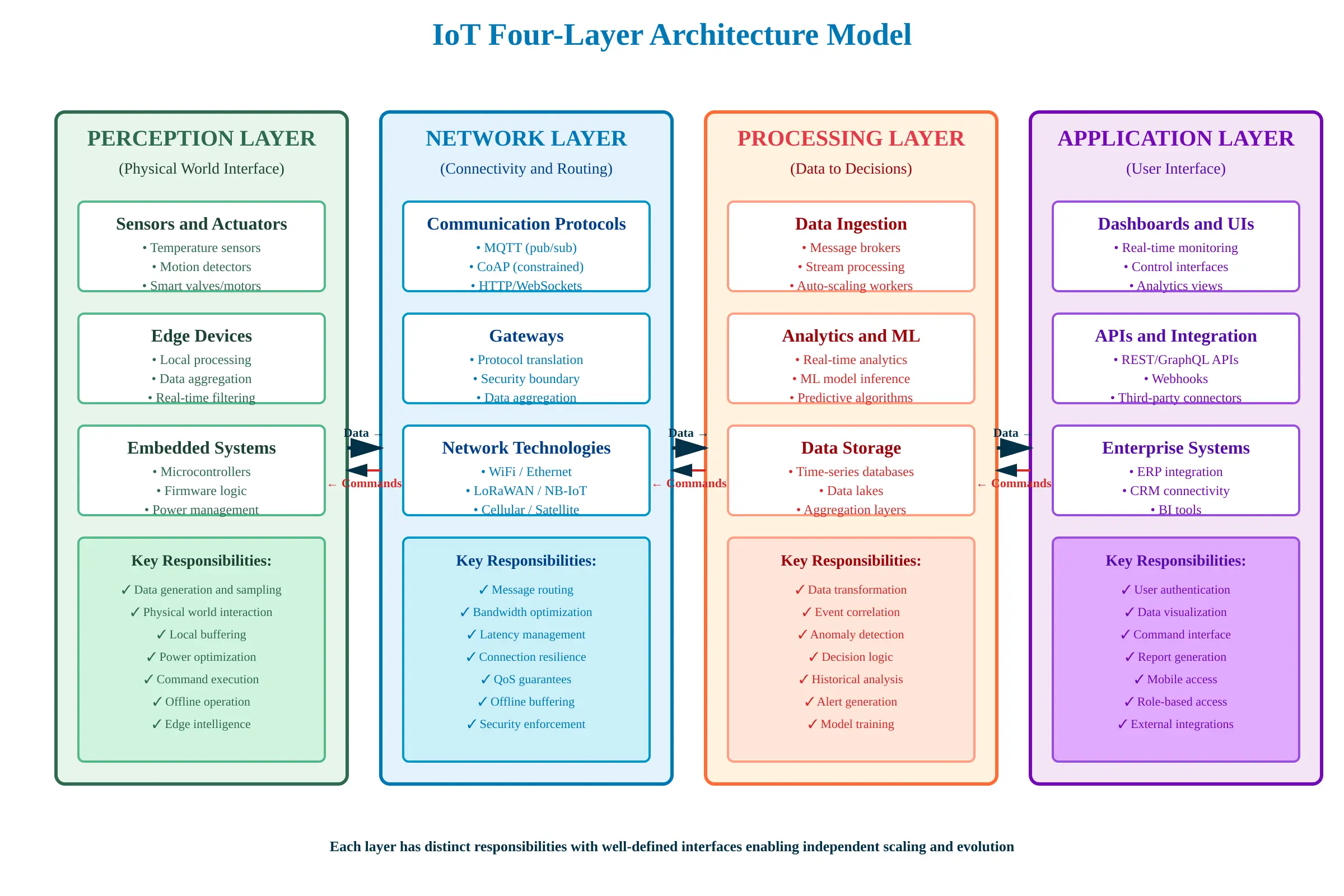

The Four-Layer IoT Architecture Model

IoT systems are organized into four distinct architectural layers. Each layer has specific responsibilities, and mixing concerns across layers creates unmaintainable systems.

| Perception Layer | Physical devices: sensors, actuators, embedded systems generating data or executing commands. This layer interacts with the physical world. |

| Network Layer | Connectivity protocols, gateways, message routing, and communication infrastructure. Moves data between perception and processing layers. |

| Processing Layer | Data ingestion, filtering, transformation, analytics, and decision-making logic. Can be split between edge and cloud. |

| Application Layer | User interfaces, APIs, dashboards, integrations with enterprise systems. How humans and other systems interact with IoT data. |

Each layer has distinct responsibilities with well-defined interfaces enabling independent scaling and evolution

Each layer communicates with adjacent layers through well-defined interfaces. Perception layer doesn’t directly talk to application layer. Network layer doesn’t make processing decisions. This separation of concerns is what allows individual components to be upgraded, scaled, or replaced without cascading changes throughout the system.

Perception Layer Architecture: Devices, Sensors, Actuators

The perception layer is where IoT systems interact with physical reality. Architectural decisions at this layer determine power consumption, data volume, network traffic, and edge processing capabilities.

System-Level Concerns at the Perception Layer:

Data generation strategy: Should sensors sample continuously or on-demand? Fixed intervals or event-driven? A temperature sensor sampling every second generates 86,400 readings per day. Sampling only when temperature changes by 1 degree might generate 20 readings per day. Both are valid architectural choices with drastically different downstream impacts.

Sampling frequency: Nyquist theorem says sample at twice the frequency of the highest-frequency component you care about. For slow-changing environmental conditions, every 5 minutes suffices. For vibration monitoring in industrial equipment, 10,000 samples per second might be required. This decision shapes everything: battery life, network bandwidth, storage costs.

Device intelligence boundaries: Where does raw sensor data become information? Should a motion sensor just report “motion detected” or should it track patterns, filter false positives, and only report actual intrusions? This boundary decision determines whether you need 100 cheap sensors with cloud processing or 100 smart sensors with edge logic.

Actuator response patterns: How do devices receive and execute commands? Immediate execution or queued for next check-in? What happens if the command fails? Retry logic, timeout handling, and failure reporting all belong in perception layer architecture.

Device Capability Design: “Dumb” Sensors vs Smart Edge Devices

The architectural decision of where intelligence resides shapes costs, capabilities, and operational complexity. This isn’t a technology choice—it’s a fundamental system design trade-off.

“Dumb” Sensors (Low Intelligence Approach):

Architecture: Sensors collect raw data and transmit everything to gateway or cloud. Minimal on-device processing, simple firmware, low compute and memory requirements.

Advantages: Cheap per unit ($5-$20). Low power consumption, battery lasts 2-5 years. Simple to manufacture and replace. Easy firmware updates (less code to go wrong). Lower development costs upfront.

Trade-offs: High network bandwidth consumption. Cloud processing costs scale linearly with device count. Latency for decisions (data must travel to cloud and back). Complete dependency on connectivity—offline functionality impossible.

When this architecture works: Low-frequency data (readings every 5+ minutes). Non-critical applications where latency doesn’t matter. Deployments with guaranteed connectivity. Cost-sensitive projects with massive device counts.

Smart Edge Devices (High Intelligence Approach):

Architecture: Devices include microprocessors capable of local processing, filtering, anomaly detection, and real-time control loops. Transmit only aggregated data, alerts, or decisions.

Advantages: Massive reduction in network traffic (90-99% less). Near-zero latency for local decisions. Works offline or with intermittent connectivity. Lower long-term cloud costs. Can implement complex logic locally.

Trade-offs: More expensive hardware ($50-$200+ per device). Higher power consumption, battery life reduced. Complex firmware, harder to debug. More expensive to develop. Harder to update (more code, more risk).

When this architecture works: Real-time control requirements (milliseconds matter). Unreliable connectivity expected. High-frequency data that would overwhelm networks. Applications where cloud processing costs would be prohibitive.

Architectural example from production: Industrial temperature monitoring with 1,000 sensors sampling every 5 seconds. Dumb approach: 1,000 sensors × 12 readings/minute × 60 minutes = 720,000 messages per hour to cloud. Monthly cloud ingestion costs: $8,000+. Smart approach: Edge devices aggregate locally, send hourly averages + threshold alerts only = 1,000 messages per hour. Monthly cloud costs: $80. The architecture decision saves $95,000 annually at scale.

Network Layer Architecture: Connectivity as a Design Constraint

Network architecture in IoT isn’t about choosing WiFi versus cellular. It’s designing for the reality that connectivity is a constraint, not a guarantee. Bandwidth costs money. Latency breaks real-time control. Power consumption drains batteries.

Bandwidth Constraints Shape Architecture:

A LoRaWAN network provides 0.3-50 kbps with range measured in kilometers but costs almost nothing to operate. WiFi provides 50+ Mbps but requires infrastructure and power. Cellular provides reliable connectivity anywhere but costs per megabyte add up with thousands of devices. Architecture must match communication patterns to network capabilities.

Architectural pattern: Local high-bandwidth networks (WiFi, Ethernet) for data aggregation at gateways. Low-bandwidth wide-area networks (LoRaWAN, NB-IoT) for remote sensor communication. Cellular as fallback for critical alerts when primary networks fail.

Latency Requirements Drive Architecture:

Industrial control systems need sub-100ms response times. WiFi can deliver this. LoRaWAN has 1-2 second latency. Satellite has 500+ millisecond latency. If latency matters, architecture must either use fast networks or move processing to the edge where network latency doesn’t matter.

Power Consumption Architectural Impact:

Always-on WiFi connections drain batteries in days. LoRaWAN devices sleep 99.9% of the time, waking only to transmit, and batteries last years. Architecture must match communication patterns to power budgets. Devices that need to last 5 years on battery can’t use connection-heavy protocols.

Messaging & Communication Architecture

Protocol selection is an architectural decision with cascading impacts on power consumption, reliability, development complexity, and operational costs.

| Protocol | Architectural Use Case | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| MQTT | Lightweight pub/sub for battery-powered devices | Requires broker (single point of failure). Quality of Service levels add complexity. |

| CoAP | RESTful pattern for ultra-constrained devices | Smallest protocol footprint but limited tooling and ecosystem support. |

| HTTP/REST | Request/response for well-connected devices, integrations | Protocol overhead too high for battery sensors. Works well for gateways and cloud APIs. |

| WebSockets | Bidirectional real-time communication | Persistent connections drain power. Best for dashboards and real-time monitoring UIs. |

| AMQP | Enterprise message queuing, guaranteed delivery | Too heavyweight for constrained devices. Excellent for backend processing pipelines. |

Routing Architecture Patterns:

Hub-and-spoke: All devices connect to central broker or gateway. Simple to implement, single point of failure. Works for small deployments (under 1,000 devices).

Hierarchical routing: Local gateways aggregate device traffic, connect to regional hubs, which connect to cloud. Reduces load on central systems, provides fault isolation. Standard for large-scale deployments.

Mesh networking: Devices relay messages for each other, self-healing topology. Complex but extremely resilient. Used when infrastructure can’t be guaranteed (military, disaster response).

Gateway Architecture Patterns in IoT Systems

Gateways are architectural boundaries, not just protocol translators. They’re where perception layer meets network layer, where trust boundaries are enforced, and where edge intelligence often resides.

Gateway Architectural Roles:

Protocol translation: Local devices speak Zigbee, Bluetooth, or Modbus. Cloud expects MQTT over TLS. Gateways bridge these worlds, converting protocols while maintaining semantic meaning.

Data aggregation and filtering: A well-designed gateway reduces cloud traffic by 80-95%. It aggregates sensor readings, filters noise, applies business rules locally, and transmits only what matters. This isn’t optimization—it’s architectural necessity at scale.

Security boundary enforcement: Gateways authenticate devices, encrypt data, enforce access policies. They’re the DMZ between untrusted sensor networks and trusted backend systems. Compromising a sensor shouldn’t compromise the cloud.

Edge compute platform: Modern gateways run containers, execute ML models, and implement control loops locally. They’re not dumb routers—they’re distributed processing nodes that bring cloud capabilities to the edge.

Offline buffering: When cloud connectivity drops, gateways buffer critical data locally, applying retention policies to prevent storage overflow. When connectivity returns, they sync intelligently without flooding the network.

Gateway Redundancy Architecture:

Single gateway = single point of failure. Production systems deploy redundant gateways with automatic failover. Active-passive, active-active, or N+1 redundancy patterns all have architectural trade-offs in cost, complexity, and failover time.

Processing Layer Architecture: Where Data Becomes Decisions

The processing layer transforms raw sensor streams into actionable intelligence. Architecture must separate concerns: ingestion, filtering, transformation, analysis, and decision-making are distinct responsibilities requiring different infrastructure.

Data Ingestion Architecture:

IoT systems receive data as continuous streams, not request/response. Architecture requires message brokers (Kafka, RabbitMQ, AWS Kinesis) that decouple producers from consumers. Ingestion pipelines must handle bursty traffic—1,000 devices might all report after a network outage ends, creating 10x normal load for 30 minutes.

Architectural pattern: Auto-scaling ingestion workers consume from queues. If queue depth exceeds threshold, spawn more workers. When queue drains, scale down. This elasticity prevents both overprovisioning (wasted costs) and underprovisioning (dropped data).

Filtering and Transformation Architecture:

Raw sensor data is rarely directly usable. Temperature in Celsius needs conversion to Fahrenheit. Accelerometer readings need conversion to g-forces. GPS coordinates need geocoding. Architecture must define where these transformations happen: at the edge (reduces cloud processing), at ingestion (before storage), or on-demand (when data is queried).

Decision Logic Architecture:

Decisions can be rule-based (if temperature exceeds 80°C, alert) or ML-based (predict equipment failure in next 48 hours). Architecture must support both. Rule engines for simple logic. Model serving infrastructure for ML inference. Workflow orchestration for complex multi-step decisions.

Architectural principle: Keep decision logic separate from data pipelines. Rules change frequently. Data pipelines should be stable. Decoupling allows updating business logic without touching ingestion or storage layers.

Edge Computing Architecture in IoT

Edge computing isn’t a trend—it’s an architectural necessity when latency matters or connectivity can’t be guaranteed. Edge architecture brings processing, storage, and decision-making physically close to data sources.

When Edge Architecture Is Mandatory:

Real-time control loops: Manufacturing robots, autonomous vehicles, safety systems—anything requiring sub-second response times. Cloud round-trip latency (50-200ms) is too slow. Edge processing delivers sub-10ms response.

Bandwidth limitations: Video analytics generating 10 Mbps per camera. Streaming video from 100 cameras to cloud requires 1 Gbps uplink—expensive or impossible. Edge architecture processes video locally, extracts metadata (person detected, license plate ABC-123), sends only results (99% bandwidth reduction).

Intermittent connectivity: Mining operations, ships at sea, remote oil platforms—locations where internet isn’t reliable. Edge architecture enables continued operations during connectivity loss, syncing to cloud when available.

Edge Architecture Components:

Local storage: Time-series databases at the edge for recent data. Retention policies automatically purge old data. Critical historical data syncs to cloud.

Processing engines: Stream processing frameworks (like Apache Flink) running on edge servers. Real-time filtering, aggregation, and decision-making without cloud dependency.

Model deployment: ML models trained in cloud, deployed to edge for inference. Edge devices run predictions locally, send results to cloud for monitoring and retraining.

Sync mechanisms: Bidirectional sync between edge and cloud. Configuration and model updates flow edge-ward. Aggregated data and alerts flow cloud-ward. Conflict resolution when both sides change data.

Cloud Processing Architecture for IoT Platforms

Cloud architecture complements edge processing by handling tasks that require massive scale, long-term storage, or cross-device intelligence.

Scalable Ingestion Pipelines:

Cloud ingestion must handle millions of messages per second during peak loads. Architecture uses horizontally scalable message brokers, auto-scaling consumer groups, and backpressure handling. If downstream systems can’t keep up, queues buffer temporarily without dropping data.

Architectural pattern: Multi-stage ingestion. Stage 1: Accept and acknowledge messages (fast). Stage 2: Validate and enrich (slower). Stage 3: Route to storage and processing (slowest). Each stage can scale independently based on load.

Stream Processing Architecture:

Real-time analytics on data streams using frameworks like Apache Kafka Streams, AWS Kinesis Analytics, or Azure Stream Analytics. Windowing, aggregations, joins between streams—all happening in real-time before data even hits storage.

Asynchronous Workflow Architecture:

IoT processing is inherently asynchronous. Sensor sends data. System processes it. Minutes or hours later, decision emerges. Architecture uses workflow engines (AWS Step Functions, Temporal) to orchestrate multi-step processes that span minutes, hours, or days.

Example workflow: Vibration sensor detects anomaly → trigger ML model inference → if failure predicted, create maintenance ticket → notify technician → wait for maintenance completion → verify issue resolved → close ticket. This workflow might take 48 hours. Architecture must maintain state throughout.

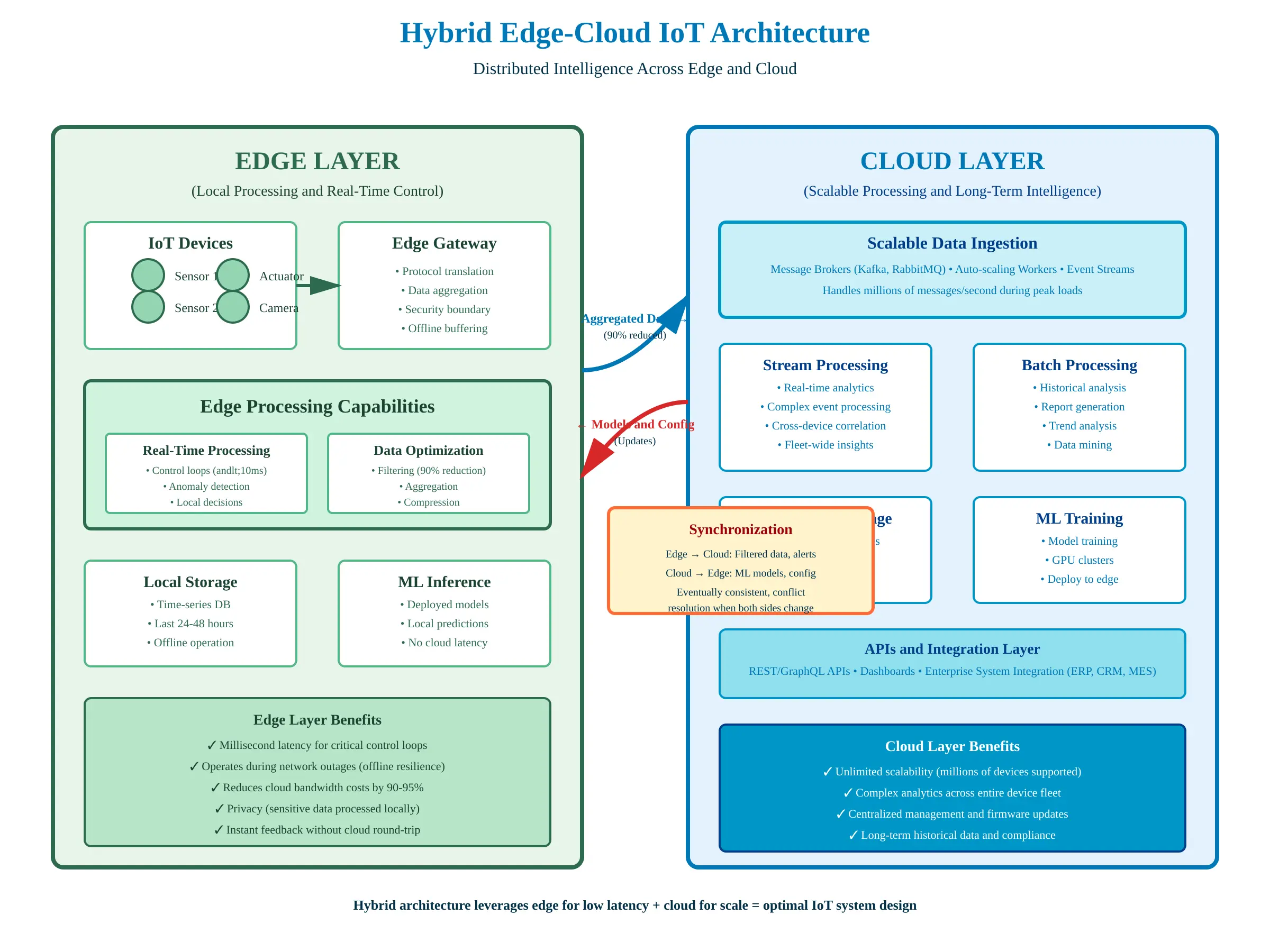

Hybrid Edge-Cloud Architecture Explained

Modern IoT systems split intelligence across edge and cloud based on latency requirements, bandwidth constraints, and computational complexity. This isn’t redundancy—it’s intentional architectural partitioning.

Architectural Partitioning Strategy:

| Processing Type | Edge | Cloud |

|---|---|---|

| Latency-critical decisions | ✓ (milliseconds matter) | ✗ (too slow) |

| Data filtering/aggregation | ✓ (reduce bandwidth) | ✗ (waste of network) |

| Real-time ML inference | ✓ (low latency) | ✓ (if latency acceptable) |

| ML model training | ✗ (limited compute) | ✓ (GPU clusters) |

| Long-term storage | ✗ (limited capacity) | ✓ (unlimited scale) |

| Cross-device analytics | ✗ (local view only) | ✓ (fleet-wide insights) |

| Offline operation | ✓ (works without internet) | ✗ (requires connectivity) |

Architectural synchronization: Edge and cloud maintain eventually consistent views of state. Edge operates autonomously. When connectivity exists, edge syncs state to cloud. Cloud can send configuration updates, model updates, or override commands back to edge. Conflict resolution logic handles cases where both sides modified the same data.

Production example: Predictive maintenance system. Edge monitors equipment vibration in real-time, detects anomalies instantly (millisecond latency), stores last 24 hours locally. Cloud trains failure prediction models on historical data from entire fleet, deploys updated models to edge weekly, provides dashboard showing fleet-wide health. Neither edge nor cloud alone would suffice—hybrid architecture delivers both real-time response and intelligent predictions.

Event-Driven Architecture in IoT Systems

IoT systems are inherently event-driven. Sensors generate events continuously—temperature readings, motion detections, threshold violations. The system reacts to these events asynchronously, not through synchronous request-response like web APIs.

Why Request-Response Doesn’t Work:

Request-response assumes client initiates interaction and waits for response. IoT sensors don’t wait—they generate data every 5 seconds whether anyone is listening. Systems can’t poll thousands of sensors continuously—it doesn’t scale and wastes power.

Event-driven architecture inverts this. Sensors publish events to message brokers. Multiple consumers subscribe to event streams—analytics pipeline, alerting system, storage layer, dashboard—all receiving the same events without coupling to each other.

Event-Driven Architecture Components:

Event producers: Sensors, gateways, edge processors—anything generating events. Producers don’t know or care who consumes events. They publish to topics or queues and continue.

Message brokers: MQTT brokers, Kafka clusters, cloud pub/sub services—infrastructure that routes events from producers to consumers reliably. Brokers provide durability (events aren’t lost), ordering guarantees, and replay capabilities.

Event consumers: Stream processors, analytics engines, alerting systems, storage writers—anything that reacts to events. Consumers can be added or removed without affecting producers. Each consumer maintains its own position in event stream.

Event schemas: Architecture must define event structure. What fields exist? What data types? How is time represented? Schema evolution strategy—how do old consumers handle new event fields?

Architectural Benefits:

Decoupling: Producers and consumers evolve independently. Adding new analytics doesn’t require changing sensor code. Scalability: Each consumer scales independently based on its processing speed. Resilience: If one consumer crashes, others continue processing. Replay: Event history can be reprocessed with new logic.

Data Architecture for IoT Applications

IoT data is time-series by nature—every sensor reading has a timestamp. Standard relational databases collapse under billions of timestamped records. Time-series data architecture is fundamentally different.

Time-Series Database Architecture:

Purpose-built databases (InfluxDB, TimescaleDB, AWS Timestream) optimize for time-series workloads. They compress data aggressively (10-100x better than general databases), support time-based queries efficiently, and handle automatic data retention policies.

Architectural pattern: Write-optimized storage for recent data (last 7-30 days). Automatic rollup to lower granularity for historical data (hourly averages instead of per-second readings). Eventually archive to cold storage (S3, Glacier) for compliance or long-term analysis.

Data Modeling for Time-Series:

Unlike relational databases with rows and columns, time-series databases organize by measurements (temperature, pressure), tags (device_id, location), fields (actual values), and timestamps. Query patterns are temporal—”show me average temperature per hour for the last week”—not relational joins.

Aggregation Strategy:

Storing every sensor reading forever is expensive and often useless. Architecture defines aggregation rules: Keep raw data for 7 days. After 7 days, downsample to 1-minute averages. After 30 days, downsample to hourly. After 1 year, keep only daily summaries. Critical anomalies always preserved at full resolution.

Data Lifecycle Management:

IoT generates petabytes over time. Architecture must address: How long is raw data retained? When does data move to cheaper storage tiers? When is data deleted? What compliance requirements exist (GDPR, HIPAA)? Automated policies enforce lifecycle rules without manual intervention.

Application Layer Architecture: Dashboards, APIs, Integrations

The application layer is where humans interact with IoT data through dashboards, mobile apps, and web interfaces. Architecturally, this layer must be completely decoupled from device-specific details.

Dashboard Architecture Patterns:

Real-time dashboards showing live sensor data require WebSocket connections for streaming updates. Historical analytics dashboards query time-series databases for trends. Architecture must support both without mixing concerns.

Architectural separation: Real-time visualization layer consumes from message streams (low latency, ephemeral). Historical analysis layer queries databases (higher latency, persistent). Same UI, different data paths.

API Architecture for External Access:

IoT platforms expose REST or GraphQL APIs abstracting internal complexity. External systems don’t query sensors directly—they query APIs that hide whether data comes from cache, database, or live stream.

API design principles: Resource-oriented (devices, readings, alerts). Pagination for large result sets. Filtering by time, device, location. Rate limiting to prevent abuse. Versioning for backward compatibility. Authentication and authorization at API boundary.

Mobile Application Architecture:

Mobile apps for IoT control and monitoring must handle offline scenarios gracefully. Architecture includes local caching, optimistic UI updates, background sync, and push notifications for alerts. Mobile apps should never directly communicate with devices—only through secure APIs.

API & Integration Architecture in IoT Platforms

IoT systems don’t exist in isolation. They integrate with ERP systems, MES platforms, CRM tools, business intelligence dashboards, and custom enterprise applications. Integration architecture determines whether these connections are maintainable or become technical debt.

Decoupling Strategy:

Direct database access from external systems = tightly coupled nightmare. Schema changes break integrations. API-based integration provides abstraction layer. IoT platform can change internal storage, processing, even protocols—as long as API contract remains stable, integrations don’t break.

Integration Patterns:

REST APIs: Standard for synchronous queries. “Get current temperature for device X.” “List all alerts from last hour.” Request-response pattern, straightforward but doesn’t scale for high-frequency data access.

Webhooks: IoT platform pushes events to external systems. “When temperature exceeds threshold, POST to this URL.” Event-driven, scalable, but requires external system to expose HTTP endpoint.

Message queues: External systems consume from same event streams as internal consumers. Kafka, RabbitMQ, cloud pub/sub services. Most flexible but requires external system to implement queue consumer.

Data export: Scheduled or on-demand bulk exports to data warehouses, data lakes. For analytics and reporting, not real-time integration. ETL pipelines move aggregated data to analytical systems.

Authentication Architecture for Integrations:

API keys for simple integrations. OAuth 2.0 for user-context integrations. Service accounts with scoped permissions for system-to-system integration. Architecture must support credential rotation without downtime.

Scalability Architecture: Designing for 10 → 10,000 → 1,000,000 Devices

Architecture that works for 10 devices fails at 10,000. Patterns that support 10,000 devices require rearchitecture for 1,000,000. Scalability isn’t an afterthought—it’s foundational architecture.

Horizontal Scaling Patterns:

Vertical scaling (bigger servers) hits limits. Horizontal scaling (more servers) scales infinitely. Architecture must support adding nodes without downtime or reconfiguration.

Stateless services: Application servers, API gateways, processing workers—all stateless. Any request can go to any server. Load balancers distribute traffic. Adding capacity = launching more instances.

Distributed message brokers: Kafka, RabbitMQ clusters partition topics across nodes. As message volume grows, add broker nodes. Partitioning spreads load automatically.

Sharded databases: Time-series data partitioned by time range or device ID. Each shard handles subset of data. Query layer aggregates across shards. Add shards to increase capacity.

Architectural Scaling Bottlenecks:

Message broker limits: MQTT brokers handle thousands of connections per node. At 100,000 devices, need broker clustering. At 1,000,000 devices, need multi-tier broker hierarchy.

Database write throughput: Time-series databases handle millions of writes per second—if properly configured. Architecture must use batch writes, appropriate indexing, and partitioning strategies.

API rate limiting: Without rate limits, one misbehaving client can overwhelm system. Architecture implements per-client rate limits, burst allowances, and backpressure signaling.

Testing Scalability Architecture:

Load testing with simulated devices at 10x expected peak. Chaos engineering—randomly killing services to verify failover works. Gradual rollout to production device fleet in percentages (1%, 5%, 25%, 100%).

Fault-Tolerance & Resilience Architecture

Devices will fail. Networks will drop. Cloud services will have outages. IoT architecture must assume failure is the norm, not the exception, and design accordingly.

Device-Level Resilience:

Local buffering: Devices buffer data locally when network unavailable. When connectivity returns, sync buffered data. Architecture must define buffer size limits, overflow behavior, data prioritization.

Exponential backoff: Failed transmissions retry with increasing delays (1s, 2s, 4s, 8s…). Prevents thundering herd when connectivity returns and all devices retry simultaneously.

Graceful degradation: If cloud unavailable, devices continue core functions using local intelligence. Reduced functionality beats complete failure.

Network-Level Resilience:

Multiple communication paths: Primary WiFi, fallback cellular, last-resort satellite. Architecture automatically switches based on availability and cost.

Gateway redundancy: Multiple gateways with automatic failover. Devices detect gateway failure and reconnect to backup within seconds.

Cloud-Level Resilience:

Multi-region deployment: Data replicated across geographic regions. If one region fails, traffic redirects to healthy region. Architecture must handle cross-region data consistency.

Service redundancy: Critical services (ingestion, processing, storage) deployed with redundancy. Load balancers detect failures and route around them. Health checks, circuit breakers, fallback mechanisms.

Dead letter queues: Messages that fail processing repeatedly go to dead letter queue for manual investigation. Prevents infinite retry loops that consume resources.

Data Resilience:

Replication across storage nodes. Automated backups. Point-in-time recovery. Immutable event logs (can reconstruct state from events if database corrupted).

Security Boundaries at the Architecture Level

Security isn’t a layer—it’s architectural boundaries defining where trust starts and ends. Every layer transition is a potential attack surface.

Device-to-Gateway Boundary:

Devices must prove identity before gateway accepts data. Mutual TLS (both device and gateway authenticate each other). Certificate-based authentication or pre-shared keys. Encrypted communication (TLS/DTLS) prevents eavesdropping and tampering.

Gateway-to-Cloud Boundary:

Gateway authenticates to cloud using certificates or API credentials. All communication encrypted. Gateway acts as trust boundary—validates device data before forwarding to cloud. Prevents compromised devices from directly attacking cloud infrastructure.

Cloud Internal Boundaries:

Ingestion services shouldn’t directly access databases. Processing services shouldn’t directly access external APIs. Principle of least privilege—each component has minimum permissions needed. Service-to-service authentication and authorization.

User-to-System Boundary:

Users authenticate via APIs. Role-based access control (RBAC) determines what data they can access. API keys, OAuth tokens, or session cookies—all with expiration. Users never access devices directly—only through controlled APIs.

Architecture principle: Defense in depth. Security at every boundary. Compromising one layer shouldn’t compromise entire system. Network segmentation, firewalls, intrusion detection at architectural level.

Common IoT Architecture Anti-Patterns

These architectural mistakes appear in proof-of-concepts that work with 10 devices and collapse in production with 10,000.

Anti-Pattern 1: Centralized Bottleneck

Single gateway for all devices. Single database for all data. Single processing server. Works fine at small scale. Becomes single point of failure and performance bottleneck at scale. Architecture must distribute load across multiple nodes from day one.

Anti-Pattern 2: Chatty Devices

Devices sending heartbeats every second. Transmitting redundant data that hasn’t changed. Over-reporting creates unnecessary network traffic, battery drain, and cloud processing costs. Architecture should transmit only on change or at reasonable intervals.

Anti-Pattern 3: Over-Clouding

Processing everything in cloud when edge could handle it. Sends video streams to cloud for simple motion detection. Sends sensor readings to cloud for local threshold checks. Results in unnecessary latency, bandwidth costs, and cloud processing expenses. Architecture should push intelligence to edge when feasible.

Anti-Pattern 4: Tight Coupling

Applications directly querying device APIs. Dashboard code that knows about sensor protocols. Integration logic that depends on database schema. Any change breaks dependent systems. Architecture must use abstraction layers (APIs) to decouple components.

Anti-Pattern 5: No Offline Strategy

System assumes always-connected. When network fails, everything stops. No local buffering, no graceful degradation, no recovery mechanism. Architecture must design for intermittent connectivity from day one.

Anti-Pattern 6: Synchronous Processing

Device sends data, waits for response before continuing. Creates timeout issues, blocks sensors unnecessarily, doesn’t scale. IoT is inherently asynchronous—architecture must embrace event-driven patterns.

Anti-Pattern 7: Ignoring Time Zones and Clock Drift

Devices using local time without timezone info. Assuming device clocks are accurate. Results in data that can’t be properly ordered or analyzed. Architecture must use UTC timestamps and account for clock drift through NTP sync.

How Architecture Decisions Shape Everything Downstream

Architecture isn’t abstract diagrams—it’s decisions that lock in performance characteristics, cost structures, security posture, and operational complexity for years.

Performance Locked In:

Decision to process in cloud vs edge determines latency forever. Choosing protocol (MQTT vs HTTP) determines power consumption. Database selection (SQL vs time-series) determines query performance. These aren’t easily changed after 10,000 devices deployed.

Cost Structure Locked In:

Dumb sensors with cloud processing = ongoing cloud costs scaling with device count. Smart sensors with edge processing = higher upfront hardware costs but minimal cloud costs. Architecture determines whether costs grow linearly with scale or stay flat.

Security Posture Locked In:

Architecture with no security boundaries can’t be secured later without fundamental redesign. Where authentication happens, how data is encrypted, what trust assumptions exist—all architectural decisions that can’t be retrofitted.

Operational Complexity Locked In:

Complex architectures with many moving parts require larger operations teams. Simple architectures with clear boundaries are easier to monitor and debug. Architecture determines operational burden for system’s lifetime.

The hard truth: Bad architecture can’t be fixed with better code. It requires fundamental redesign. Good architecture allows system to evolve gracefully. Poor architecture creates technical debt that compounds over time.

When IoT Architectures Fail in Production

These are purely architectural failures—not business failures, not operational mistakes, but fundamental design flaws that cause system collapse.

Failure Mode 1: Thundering Herd

Network outage affects 10,000 devices. When connectivity returns, all devices reconnect simultaneously. Message broker overwhelmed. System crashes. Occurs when architecture lacks connection backoff and jitter. Fix requires device firmware changes—expensive at scale.

Failure Mode 2: Cascading Failures

Database slows down. Ingestion workers wait for database. Queue fills up. More workers spawn to process queue. All workers blocked on database. Entire system deadlocked. Architecture lacked circuit breakers and backpressure handling.

Failure Mode 3: Data Loss from Over-Retention

No data lifecycle policies. Time-series database grows unbounded. Disk fills up. Can’t ingest new data. Months of data lost because architecture assumed infinite storage.

Failure Mode 4: Security Breach from Flat Architecture

No security boundaries between layers. Compromised sensor gains access to entire database. Happens when architecture treats internal network as trusted. Defense in depth missing.

Failure Mode 5: Inability to Update Firmware

No over-the-air update mechanism in architecture. Bug found in device firmware. 50,000 devices deployed globally. Physical access required for updates. Architecture oversight costs millions.

Real production failure: Smart building system with all sensors reporting to single gateway. Gateway hardware failure took down monitoring for entire building. No failover because architecture assumed single gateway sufficed. Building lost HVAC control for 6 hours during summer. Architectural fix required deploying redundant gateways with automatic failover—$150K emergency retrofit.

How Mature Teams Approach IoT Architecture Design

Experienced IoT architects follow principles learned from production failures, not from textbooks.

Principle 1: Design for Failure, Not Success

Assume devices fail, networks drop, services crash. Architecture that handles these gracefully works in production. Architecture that assumes perfect conditions fails immediately.

Principle 2: Decouple Layers with Clean Interfaces

Each layer communicates through well-defined protocols and APIs. Changes to one layer don’t cascade to others. Enables independent evolution and testing.

Principle 3: Push Intelligence to Edges When Latency Matters, Pull to Cloud When Scale Matters

Don’t process everything in one place. Hybrid architecture leverages strengths of both edge (low latency) and cloud (massive scale, complex analytics).

Principle 4: Make Systems Observable

Telemetry from every layer. Metrics, logs, traces. Can’t debug what can’t observe. Architecture must include observability as first-class concern, not afterthought.

Principle 5: Plan for Evolution

Architecture must support firmware updates, protocol changes, scaling, new device types—all without breaking existing deployments. Versioning, backward compatibility, graceful migration paths.

Principle 6: Start Simple, Add Complexity When Needed

Don’t over-architect for scale that doesn’t exist. Start with simplest architecture that meets current needs. Add complexity (sharding, edge processing, redundancy) when growth demands it. Premature optimization creates unmaintainable systems.

Principle 7: Security is Architectural, Not Operational

Can’t bolt security onto bad architecture. Trust boundaries, authentication, encryption must be designed into system from day one.

Closing Perspective: IoT Architecture as a Living System

IoT architecture isn’t a one-time design document created before development starts. It’s a living system that evolves as device fleets grow, requirements change, technologies mature, and lessons are learned from production.

The architecture must support this evolution without requiring complete rebuilds or breaking deployed devices. This is what separates proof-of-concepts from production systems that scale to millions of devices and operate for decades.

Architecture Evolution Patterns:

Adding device types: New sensors with different capabilities. Architecture must accommodate through abstract interfaces, not hardcoded logic.

Protocol changes: Migrate from MQTT to newer protocol. Architecture enables gradual rollout—old and new protocols coexist during transition.

Scaling infrastructure: Add database shards, broker nodes, processing workers. Architecture allows horizontal scaling without downtime.

Changing business logic: New alerting rules, different aggregation strategies, updated ML models. Architecture separates business logic from infrastructure so these changes don’t require architectural redesign.

The Fundamental Reality:

Architectural decisions made in the first 30 days of an IoT project determine whether the system can scale to millions of devices or collapses at 10,000. Whether devices can be updated remotely or require expensive field visits. Whether the system handles network outages gracefully or fails completely. Whether cloud costs grow linearly with devices or stay manageable.

IoT software development companies that understand these architectural realities ship systems that work at scale. Those that ignore architecture ship prototypes that can’t survive production reality.

Choose architecture wisely. Design for reality, not ideal conditions. Build systems that acknowledge devices fail, networks drop, and edge intelligence isn’t optional—it’s the only way IoT works at scale. Architecture determines everything: performance, cost, scalability, security, and whether the system survives production.

FAQ : IoT App Architecture

IoT architecture is the end-to-end system design defining how data flows from sensors through networks to decision-making systems while handling failures, intermittent connectivity, and massive scale. Good architecture determines whether systems survive production or collapse at 10,000 devices, shaping performance, costs, and operational complexity for years.

IoT operates under constraints web apps don’t face: intermittent connectivity requiring offline operation, battery-powered devices limiting communication, continuous sensor streams instead of user requests, distributed processing across edge and cloud, firmware updates to remote devices that can’t fail, and real-time control loops needing millisecond response times.

Modern IoT uses hybrid architecture splitting intelligence strategically. Edge handles real-time control loops (milliseconds matter), data filtering (reduce bandwidth 90%+), and offline operation. Cloud handles fleet-wide analytics, long-term storage, ML model training, and complex processing requiring massive compute. Neither alone suffices—both together deliver optimal results.

Four architectural layers with distinct responsibilities: Perception layer (sensors, actuators, devices generating data), Network layer (protocols, gateways, connectivity infrastructure), Processing layer (data ingestion, filtering, transformation, analytics split between edge and cloud), Application layer (dashboards, APIs, integrations with enterprise systems). Separation enables independent scaling and evolution.

Dumb sensors collect raw data, transmit everything to cloud, cost $5-$20, last years on battery but create high network and cloud processing costs. Smart edge devices process locally, filter data, cost $50-$200+, consume more power but reduce cloud traffic 90%+, enable offline operation, and deliver instant local decisions. Trade-off: upfront hardware costs versus ongoing operational expenses.

IoT sensors generate continuous event streams regardless of whether anyone is listening—request-response patterns don’t work. Event-driven architecture with message brokers decouples producers (sensors) from consumers (analytics, storage, alerts). If one consumer fails, others continue. Events can be replayed. System scales by adding consumers independently without changing sensor code.

Architecture must assume failure as default state. Devices buffer data locally during outages with exponential backoff retry. Gateways provide redundancy with automatic failover. Cloud deploys across regions with circuit breakers. Message queues prevent data loss. Graceful degradation maintains core functions during partial failures rather than complete system collapse.

Centralized bottlenecks (single gateway/database), chatty devices sending redundant data, over-clouding when edge could process locally, tight coupling between layers, no offline strategy, synchronous processing blocking sensors, and ignoring time zones. These work with 10 devices but cause catastrophic failures at 10,000 devices requiring expensive architectural redesigns.

Architecture locks in cost structure permanently. Dumb sensors with cloud processing create ongoing costs scaling linearly with device count—$8,000/month at 1,000 devices. Smart edge architecture has higher upfront hardware costs but minimal cloud expenses—$80/month for same deployment. Protocol choice affects power consumption and battery replacement frequency. Database selection determines storage costs at scale.

Edge versus cloud processing split, messaging protocols (MQTT, CoAP, HTTP), device intelligence level (dumb vs smart sensors), security boundaries and authentication, time-series database selection, horizontal scaling patterns, event-driven architecture with message queues, gateway redundancy strategy, data lifecycle policies, and firmware update mechanisms. These foundational decisions determine system scalability and operational success.

Reviewed & Edited By

Aman Vaths

Founder of Nadcab Labs

Aman Vaths is the Founder & CTO of Nadcab Labs, a global digital engineering company delivering enterprise-grade solutions across AI, Web3, Blockchain, Big Data, Cloud, Cybersecurity, and Modern Application Development. With deep technical leadership and product innovation experience, Aman has positioned Nadcab Labs as one of the most advanced engineering companies driving the next era of intelligent, secure, and scalable software systems. Under his leadership, Nadcab Labs has built 2,000+ global projects across sectors including fintech, banking, healthcare, real estate, logistics, gaming, manufacturing, and next-generation DePIN networks. Aman’s strength lies in architecting high-performance systems, end-to-end platform engineering, and designing enterprise solutions that operate at global scale.