Key Takeaways

-

In blockchain systems, private keys are authority objects, not data—possession alone grants irreversible control over assets in a crypto wallet.

-

Cryptographic failures overwhelmingly result from poor key lifecycle management, not broken algorithms, as emphasized by NIST and global security standards.

-

Blockchain systems use capability-based authority, not identity-based authentication—there is no account recovery, revocation, or secondary verification.

-

Key exposure is a terminal failure at the protocol level; blockchains cannot distinguish legitimate use from theft if a valid signature is presented.

-

The cryptographic key lifecycle spans generation, storage, usage, duplication, migration, rotation, and destruction—each phase introduces unique risks.

-

Entropy quality at key generation is foundational; weak randomness permanently compromises security and cannot be fixed later.

-

Private keys are generated as high-entropy random scalars, while public keys are derived via one-way elliptic curve cryptography, making reversal computationally infeasible.

-

Wallet addresses are derived from public keys and can be shared freely; private keys must never be exposed or duplicated unnecessarily.

-

Key representation formats (raw memory, hex, mnemonics, encrypted storage) improve usability but increase exposure risk, especially mnemonic phrases.

-

Persistent storage and backups multiply attack surfaces; each additional copy of a private key fragments authority and increases compromise risk.

-

Keys used frequently in hot wallets or automated systems face significantly higher cumulative exposure than offline or cold-stored keys.

-

Key migration and duplication are inherently risky operations; they can be reduced but never made completely safe.

-

Blockchains do not support key revocation—the only response to suspected compromise is key rotation and asset migration.

-

Secure destruction of private keys is difficult due to residual data, backups, logs, and replication layers, leaving long-term residual risk.

-

Effective crypto wallet architecture must prioritize minimal exposure, controlled persistence, strict migration handling, and lifecycle-aware security design.

-

NIST’s cryptographic key management framework confirms that private keys must be protected across their entire lifecycle, not just during signing operations.

In modern cryptographic systems, especially blockchain networks, private key material represents the highest level of authority. Unlike passwords or authentication tokens that merely verify identity, private keys function as capability-based objects of authority. Possession of a private key alone is enough to gain full control over the associated assets held inside a crypto wallet. Because of this, understanding the cryptographic key lifecycle is absolutely critical for anyone designing, using, or securing a crypto wallet.

This lifecycle-based view of cryptographic keys is not theoretical. It is formally defined and recommended by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) [1] , the primary U.S. government authority on cryptography. NIST explicitly states that cryptographic keys must be protected throughout their entire lifecycle, from generation to destruction, because failures most commonly occur due to improper key management rather than weaknesses in cryptographic algorithms.

Multiple government and standards organizations emphasize that most cryptographic failures arise from poor key management rather than weaknesses in cryptographic algorithms themselves.

Improper key generation, storage, handling, and destruction are the primary causes of cryptographic system compromise, even when strong algorithms are used.

Many users and even developers mistakenly treat private keys as ordinary data that can be copied, backed up, or restored like a file inside a cryptocurrency wallet. This assumption is dangerous. A private key grants irreversible authority. Whoever controls the key can sign transactions permanently, with no option for reversal or recovery. Proper lifecycle management is therefore essential for safeguarding digital assets stored in any crypto wallet, whether software-based, hardware-based, or custodial.

Why Private Keys Are Not “Data” but Authority Objects in the Cryptographic Key Lifecycle

Capability-based Control vs Identity-based Systems

Traditional IT systems rely on identity-based authority. A user authenticates themselves, the system verifies their identity, and permissions are granted accordingly. Blockchain systems, and by extension every crypto wallet built on top of them, operate under a fundamentally different model. Authority is tied directly to possession of a private key, not to identity.

If a private key used by a crypto wallet is exposed, there is no secondary verification step. The blockchain protocol does not question intent or legitimacy, it simply executes the signed instruction. This makes minimizing exposure at every stage of the cryptographic key lifecycle essential, as familiar safeguards such as password resets, account freezes, or customer support intervention do not exist at the protocol level.

Irreversibility as a First-order Design Constraint

Irreversibility is a defining property of blockchain systems. Once a transaction is signed using a private key and broadcast by a crypto wallet and then confirmed on-chain, it cannot be undone. Blockchain transactions are designed to be irreversible by protocol. Once a transaction is cryptographically signed and confirmed on-chain, it cannot be reversed or modified. This property is explicitly documented in official blockchain wallet protocol specifications and government cryptography guidance. This permanent finality means that even minor lifecycle mistakes inside a crypto wallet can lead to irreversible losses.

As a result, every stage of the cryptographic key lifecycle, from generation to destruction, must be treated as security-critical. There is no margin for error when private keys are involved.

Why Key Exposure Is a Terminal Failure at the Protocol Layer

At the protocol level, blockchains cannot distinguish between legitimate and malicious use of a private key. If an attacker obtains the key from a compromised crypto wallet, the system treats them as the rightful owner. Unlike traditional systems that can flag suspicious behavior or lock accounts, blockchains simply process valid signatures.

This reality makes preventing key exposure throughout the cryptographic key lifecycle the single most important security objective for any crypto wallet architecture.

Entropy Origins and the Problem of Key Birth in the Cryptographic Key Lifecycle

Environmental Entropy vs Deterministic Derivation

Private key security begins at the moment of generation and depends heavily on randomness, also known as entropy. Crypto wallets may generate keys using environmental entropy, which collects randomness from physical or system-level sources or through deterministic derivation, where a master seed generates multiple keys in a hierarchical deterministic (HD) crypto wallet.

Both methods can be secure, but only if entropy quality is high. Weak entropy has caused real-world failures, including cases where attackers reconstructed private keys without breaking cryptographic algorithms. These incidents demonstrate that flaws at the very start of the cryptographic key lifecycle can permanently compromise the security of an entire crypto wallet.

Entropy Depletion, Reuse and Predictability Risks

Entropy is not unlimited. In constrained environments such as virtual machines, mobile devices or embedded hardware wallets, poor entropy management can result in predictable or correlated keys. Once a private key is weak at birth, no later crypto wallet software update or encryption layer can make it secure.

This highlights why key quality must be guaranteed during generation, as it forms the foundation of the entire cryptographic key lifecycle.

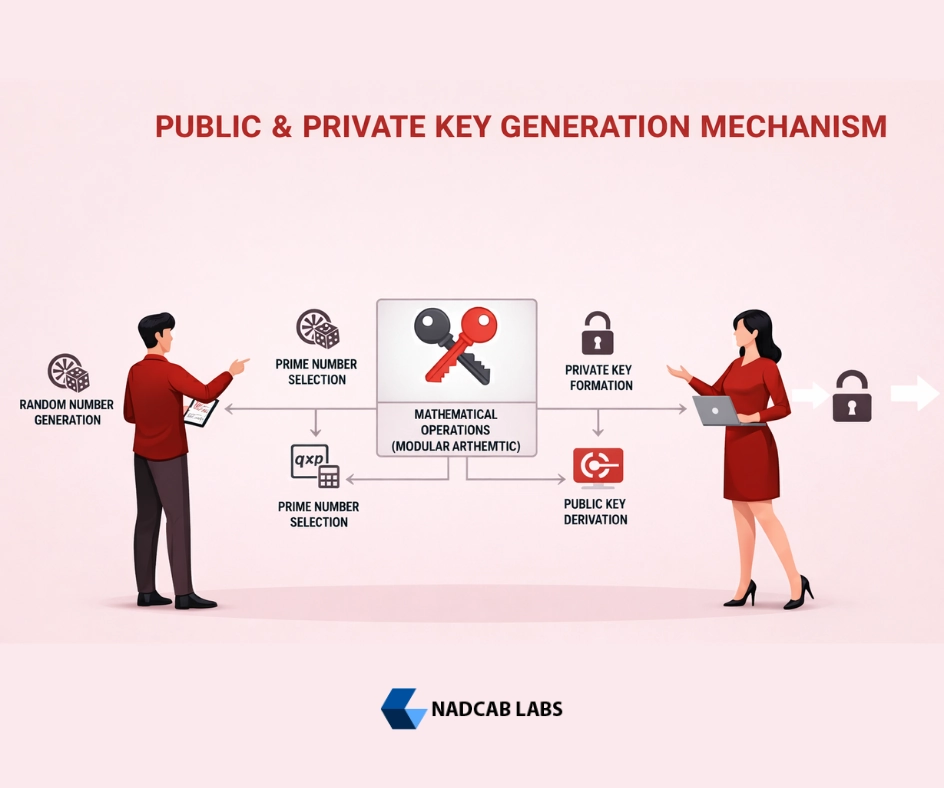

Complete Mechanism of Private Key and Public Key Generation

Step 1: Private Key Generation

A private key in blockchain systems is essentially a very large random number. For standards like secp256k1, used by both Bitcoin and Ethereum crypto wallets, this is a 256-bit number selected uniformly at random from a specific range. The random number generation is done using cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generators (CSPRNGs) or hardware random number generators (HRNGs).

The resulting private key must be greater than zero and less than the order of the elliptic curve used. If it falls outside that range, the crypto wallet discards it and restarts the generation process with fresh entropy.

Step 2: Public Key Derivation

Once a private key has been securely generated, the corresponding public key is derived through a deterministic mathematical process called elliptic curve multiplication:

Public Key = Private Key × G

In this formula, G is a fixed point on the elliptic curve. The result of multiplying the private key (a scalar) with G yields a pair of coordinates (x, y) on the curve, which make up the public key. Importantly, this derivation is one-way. Given the public key used by a crypto wallet, it is computationally infeasible to extract the private key due to the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP).

Step 3: Address Generation

In many blockchain systems, the public key is then transformed into an address that a crypto wallet displays to users. For example, Bitcoin crypto wallets use a sequence of hashing functions (SHA-256 followed by RIPEMD-160) and add network prefixes and checksums to produce a human-readable address. In Ethereum crypto wallets, the public key is hashed using Keccak-256, and the last 40 hexadecimal characters form the address.

Crucially, the private key is never revealed during this process. The public address can be shared freely, but only the private key holder, via their crypto wallet, can sign transactions.

Key Material Representation Inside Crypto Wallet Software Systems

Private keys are mathematically simple scalar values, but in crypto wallet software they are represented in various encoded formats. These include raw hexadecimal strings, Base58 encodings, or human-friendly mnemonic phrases that represent keys in readable words. While mnemonic representations greatly aid in user retainability and backup convenience within a crypto wallet, they also introduce distinct exposure risks if mishandled, such as screenshots, clipboard leaks, or phishing attacks.

When private keys are used to sign transactions, they must be loaded into active memory by the crypto wallet. Official security [2] guidance confirms that private keys must exist in system memory during cryptographic operations, creating temporary exposure windows. Government standards highlight memory exposure as a critical risk during key usage, particularly in software-based cryptographic systems. Additionally, converting keys between formats creates temporary copies in memory or logs, which may expose sensitive key material if not handled correctly.

Common Private Key Representation Formats

| Representation Format | Human Usability | Exposure Risk | Common Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw scalar in memory | None | High | Memory scraping, malware |

| Hex / Base58 encoding | Low | Medium | Logging, system dumps |

| Mnemonic phrase | High | Very High | Screenshots, social engineering |

| Encrypted serialized storage | Medium | Medium | Encryption key mismanagement |

| Cloud-backed key formats | Medium | Very High | Remote compromise |

This table illustrates how even representation formats that improve crypto wallet usability can increase exposure risk, making careful lifecycle management a necessity.

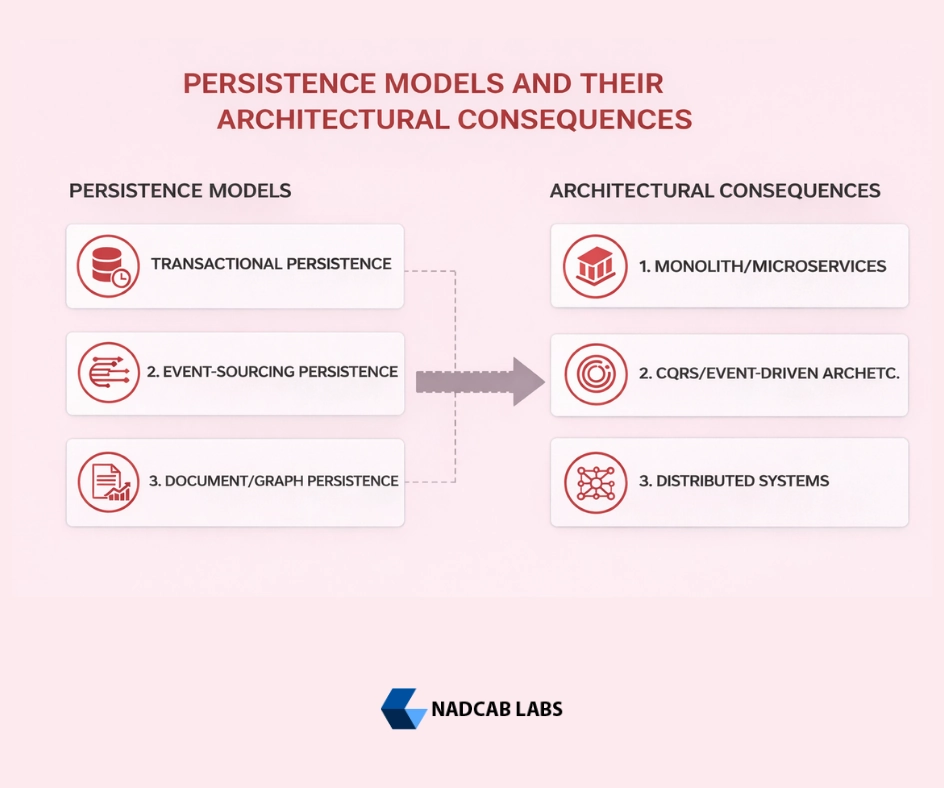

Persistence Models and Their Architectural Consequences in Crypto Wallets

Storing private keys only in volatile memory (RAM) minimizes exposure because the key disappears when power is lost. However, volatile storage cannot persist across reboots, making recoverability difficult for most crypto wallet users. In contrast, persistent storage, writing keys to disk, flash memory, or backed-up formats, improves usability but dramatically increases the attack surface.

Government cryptographic standards warn that persistent storage of private keys significantly increases attack surface, particularly when keys are stored across multiple devices, backups, or cloud environments. Persistent storage multiplies exposure points throughout the cryptographic key lifecycle. Backups further multiply attack surface points. Cloud sync, offline copies, and device backups may provide recovery convenience, but each additional storage location is an opportunity for compromise.

Comparative View of Persistence Models

| Storage Model | Copies | Auditability | Long-Term Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory-only | 1 | High | Low |

| Encrypted local storage | 2–5 | Medium | Medium |

| Multi-location backups | 5+ | Low | High |

| Cloud sync & external devices | 10+ | Very Low | Very High |

Custody systems and crypto wallet designers must carefully balance usability and persistence risk, as persistence directly affects the cryptographic key lifecycle risk profile.

Key Usage Phases and Temporal Risk Expansion

Private keys that are actively used by a crypto wallet, such as hot wallets signing frequent transactions, face greater cumulative risk compared to keys stored offline. This is one reason why hot crypto wallets are generally 5–10 times more likely to be compromised than cold wallets.

Each time a key is loaded into memory to sign a transaction, a new exposure window opens. Automated trading bots, DeFi protocols, and high-frequency signing operations further expand these risk windows. Operational patterns such as shared servers, multi-tenant environments, and long-running services amplify exposure risk even further.

Build My Crypto wallet Now!

Turn your dream into reality with a powerful, secure crypto wallet built just for you. Start building now and watch your idea come alive!

Key Duplication, Migration and Authority Fragmentation

Although a private key is logically unique, it is physically copyable. Once a crypto wallet duplicates a key through backups or exports, authority is effectively fragmented. Each copy increases the potential attack surface, whether stored on a USB drive, a secondary device or a cloud backup.

Moving keys between crypto wallets, hardware devices, or software environments is another risky phase in the cryptographic key lifecycle. During import and export operations, keys may pass through insecure channels, temporary storage or human interfaces, all of which can introduce vulnerabilities. Migration can only be risk-reduced, never made completely safe.

Degradation, Compromise and Silent Failure Modes

Private keys may suffer partial exposure without obvious signs of compromise. Blockchain systems and crypto wallets cannot inherently detect theft, they only validate signatures. Only after irreversible damage, such as unauthorized asset transfers, does compromise become apparent.

Because cryptographic systems offer no mechanism for recognizing suspected compromise, best practices require treating any sign of exposure as full compromise. Crypto wallet lifecycle strategies must therefore plan for rapid asset management and emergency response.

Key Revocation Is Not a Protocol Concept

Unlike identity-based systems that maintain revocation lists, blockchains do not track which keys are valid or invalid. Authority is derived solely from possession of the private key. When a crypto wallet key is believed to be compromised, the only practical mitigation is key rotation and asset migration, not revocation.

This means crypto wallet users and custodians must incorporate rotation strategies into their cryptographic key lifecycle planning.

End-of-Life Destruction, Abandonment and Residual Risk

Securely destroying a private key in modern crypto wallet environments is extremely difficult. Official lifecycle models divide cryptographic keys into pre-operational, operational, post-operational, and destroyed states. These models emphasize that improper destruction or residual data exposure can leave cryptographic authority unintentionally active beyond its intended lifecycle. Data replication layers, caching mechanisms, and backups may retain remnants of key material long after deletion attempts. Residual exposure from logs, snapshots, and archives can persist for years.

Although destruction prevents future use, it cannot erase historical authority or transactions already signed. This again emphasizes the need for proactive lifecycle management rather than reactive remediation.

Architectural Implications of the Full Cryptographic Key Lifecycle

Designing crypto wallets and custody systems with full awareness of the cryptographic key lifecycle requires minimizing key exposure, strictly controlling duplication, enforcing secure migration procedures, and ensuring proper end-of-life destruction.

These principles align directly with NIST’s official [3] key management framework, which treats private keys as high-risk security objects requiring protection across their entire lifecycle, not merely during cryptographic operations.

All cryptographic key management practices described in this article align with internationally recognized government standards. These standards are widely adopted by financial systems, security frameworks, and blockchain custody solutions to ensure cryptographic keys remain secure throughout their entire lifecycle .

Frequently Asked Questions

The cryptographic key lifecycle describes every stage a private key passes through, starting from secure generation with high entropy, followed by usage, storage, backup, migration, optional rotation, and final destruction. Proper lifecycle management ensures that private keys used within a crypto wallet remain protected against threats such as malware, unauthorized access, and operational mistakes at every phase of their existence.

Private keys provide direct authority to control assets and sign transactions within a crypto wallet, making them more powerful than traditional credentials. In the cryptographic key lifecycle, private keys cannot be reset or revoked if compromised, and any exposure usually results in irreversible asset loss due to the trustless nature of blockchain systems.

A private key is confidential data used to sign transactions, while a public key is mathematically derived from it and shared openly for verification. This one-way relationship, enforced by cryptographic protections, ensures that within the cryptographic key lifecycle a public key cannot reveal the private key used by a crypto wallet.

No, blockchains do not support private key revocation because they only verify valid signatures, not key trust status. Within the cryptographic key lifecycle, the only practical mitigation is migrating assets from the compromised crypto wallet to a newly generated private key before misuse occurs.

Entropy represents the randomness used during private key creation and is critical to the cryptographic key lifecycle. High entropy ensures keys are unpredictable, while weak entropy can result in vulnerable private keys that attackers can reconstruct, compromising the security of a crypto wallet from the moment of generation.

Mnemonic phrases provide a human-readable backup of the seed used to derive private keys in a crypto wallet. Within the cryptographic key lifecycle, they simplify recovery but carry the same authority as the private key itself, meaning exposure grants attackers full control over associated assets.

Private keys must temporarily exist in system memory during signing operations, creating a short but dangerous exposure window. In the cryptographic key lifecycle, malware or memory scraping attacks can extract keys from an active crypto wallet if memory protections or hardware isolation are insufficient.

Cloud backups increase convenience but significantly expand the attack surface for private keys. From a cryptographic key lifecycle perspective, storing crypto wallet keys online introduces risks such as remote breaches, misconfigurations, and unauthorized access, making offline backups a safer alternative for high-value assets.

Private key rotation depends on usage frequency, threat exposure, and asset value. In the cryptographic key lifecycle, keys used regularly or on internet-connected crypto wallet environments should be rotated sooner, especially if exposure or system compromise is suspected.

Any suspected private key exposure should be treated as complete compromise. According to cryptographic key lifecycle best practices, assets must be immediately migrated to a newly generated crypto wallet, as blockchain systems offer no partial revocation or recovery once authority is lost.

Reviewed & Edited By

Aman Vaths

Founder of Nadcab Labs

Aman Vaths is the Founder & CTO of Nadcab Labs, a global digital engineering company delivering enterprise-grade solutions across AI, Web3, Blockchain, Big Data, Cloud, Cybersecurity, and Modern Application Development. With deep technical leadership and product innovation experience, Aman has positioned Nadcab Labs as one of the most advanced engineering companies driving the next era of intelligent, secure, and scalable software systems. Under his leadership, Nadcab Labs has built 2,000+ global projects across sectors including fintech, banking, healthcare, real estate, logistics, gaming, manufacturing, and next-generation DePIN networks. Aman’s strength lies in architecting high-performance systems, end-to-end platform engineering, and designing enterprise solutions that operate at global scale.