Key Takeaways: Security Risks in IoT Applications

- Physical Access Changes Everything:

Devices deployed in public or uncontrolled spaces enable physical attacks that are impossible in traditional data center environments.

- Attack Surface Multiplies Geometrically:

Each IoT device introduces five to eight distinct attack vectors spanning hardware, firmware, network, gateway, and cloud layers.

- Shared Credentials Equal Fleet Compromise:

A single breached device using shared credentials can compromise the entire fleet, creating systemic vulnerability across deployments.

- Update Mechanisms Become Attack Vectors:

Compromised firmware or OTA infrastructure turns update pipelines into weapons capable of infecting every device simultaneously.

- Gateways Concentrate Critical Risk:

Gateway compromise provides the same access as breaching every connected device—plus lateral movement into backend systems.

- Compliance Drives Architecture Decisions:

Regulatory requirements must shape architecture from the start; retrofitting compliance later costs 10–50× more.

- Detection Blind Spots Are Structural:

Traditional monitoring fails because IoT behavior varies widely and attacks often manipulate data without triggering network anomalies.

- Security Is an Architecture Constraint:

Security defines which architectures are viable, which deployments scale safely, and which business models remain sustainable.

1. Why IoT Security Is a Different Problem Than IT Security

Traditional IT security frameworks collapse when applied to connected devices—the fundamental assumptions about controlled environments, regular patching, and human oversight simply don’t exist in IoT deployments.

After two decades building IoT systems, we’ve learned that the difference between IT security and IoT security isn’t just technical—it’s philosophical. IT security assumes servers in locked data centers, networks you control, and the ability to patch systems within hours of vulnerability disclosure. IoT operates in hostile physical spaces where devices sit unattended for years, run on resource-constrained hardware that can’t support standard security tools, and communicate over networks you don’t own. We’ve seen clients migrate from web applications to IoT deployments only to discover their entire security playbook was obsolete. The challenge isn’t that IoT is harder—it’s that IT security models are built on assumptions that IoT environments violate at every level.

IoT Security: The practice of protecting distributed, resource-constrained devices operating in physically accessible environments over multi-year lifecycles, where security failures can cause physical harm, operational disruption, and safety incidents beyond traditional data breaches.

Critical Distinctions: IT vs IoT Security

- Environment Control: IT assumes controlled data centers; IoT operates in hostile physical spaces

- Patch Cadence: IT enables rapid patching; IoT devices may run unpatched for years

- Failure Impact: IT failures compromise data; IoT failures compromise physical safety

- Resource Availability: IT has abundant compute/memory; IoT severely constrained

- Physical Accessibility: Devices deployed in public spaces create attack vectors impossible in data centers

- Resource Constraints: Limited CPU/memory prevent implementing standard encryption and authentication protocols

- Lifespan Mismatches: Devices outlive their security model by 5-10 years creating permanent vulnerabilities

- Safety Implications: Security failures mean physical harm, not just data breaches

“The moment we treat IoT security like web security, we’ve already lost. The attack surface, threat model, and failure modes are fundamentally incompatible.”

Manufacturing Client Case Study: A manufacturing client deployed 2,000 sensors using their standard IT security protocols. Within six months, 300 devices were compromised through physical USB access—an attack vector their web-focused security team never considered. The $180,000 replacement cost taught us that physical security must be baked into the threat model from day one, not added as an afterthought.

![]()

2. Expanding Attack Surface in IoT Ecosystems

Traditional applications have defined perimeters. IoT ecosystems have attack surfaces that expand geometrically with each component—every sensor, gateway, network hop, cloud service, and user interface represents potential compromise.

We’ve architected systems where a single vulnerability in a $12 sensor exposed the entire cloud infrastructure serving 50,000 devices. The attack surface in IoT isn’t additive—it’s multiplicative. Each device doesn’t just add one attack vector; it adds the device itself, its firmware, network interface, local storage, update mechanism, API endpoints, physical access points, and trust relationships with other components.

Attack Surface Multiplier: Each device adds 5-8 attack vectors

- Device Layer: Firmware, physical access, debug interfaces

- Network Layer: Protocol vulnerabilities, MITM opportunities

- Identity Layer: Credentials, certificates, authentication mechanisms

- Cloud Layer: APIs, data storage, admin interfaces

- Edge devices multiply faster than security teams can audit

- Third-party integrations create uncontrolled entry points

- Legacy protocols required for interoperability introduce known vulnerabilities

- Each integration point between device-gateway-cloud becomes an attack seam

“In IoT, the attack surface isn’t just large—it’s distributed across environments you don’t control, connected by protocols you can’t fully secure, running on hardware you can’t easily patch.”

Agricultural IoT Deployment: An

agricultural IoT app deployment had 47 distinct attack vectors per field station. When we discovered a vulnerability in the cellular modem firmware, we couldn’t patch it without physically visiting 1,200 remote locations. The 8-month remediation window cost $340,000 and exposed the client to continuous risk during the rollout.

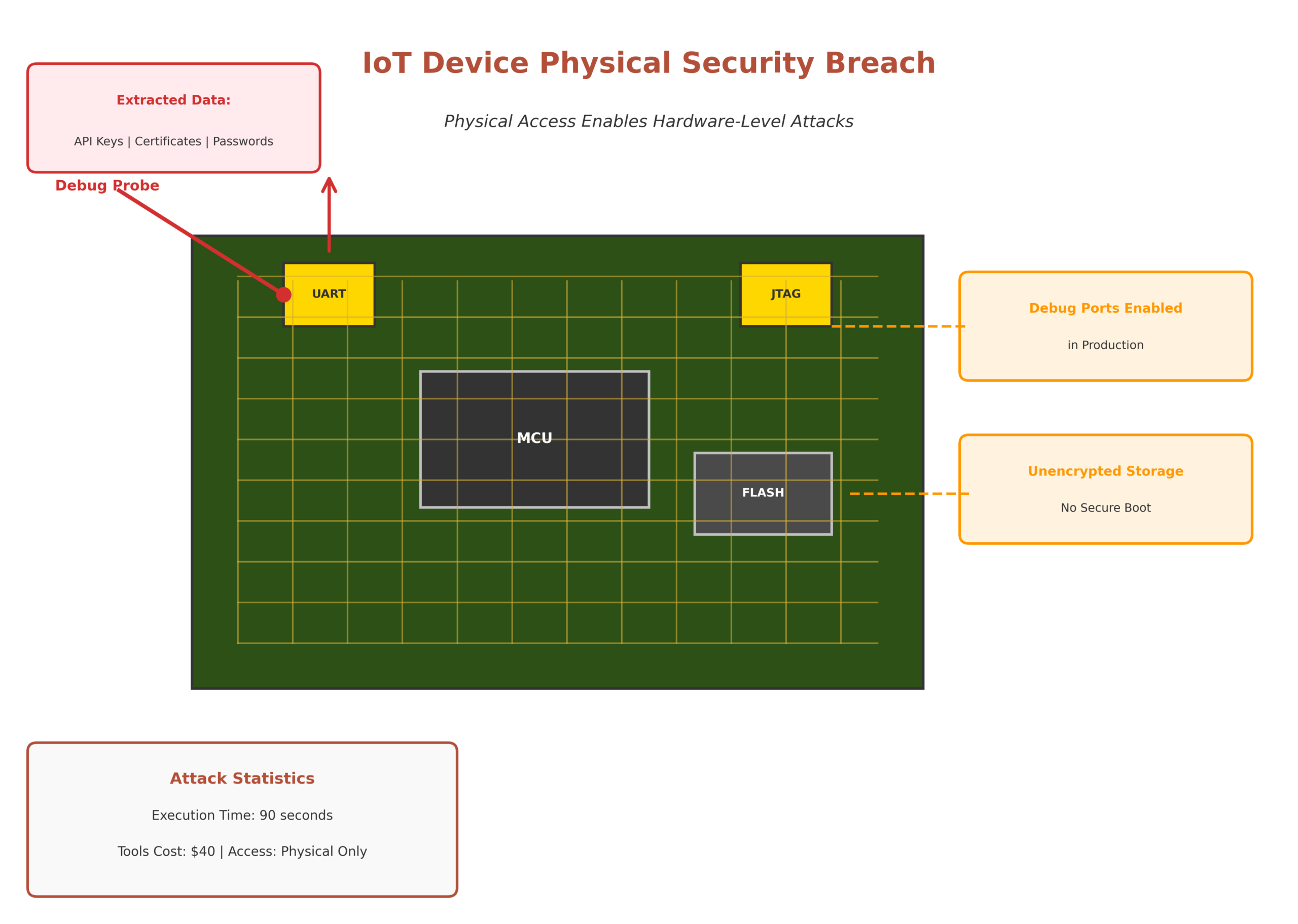

3. Device-Level Security Risks

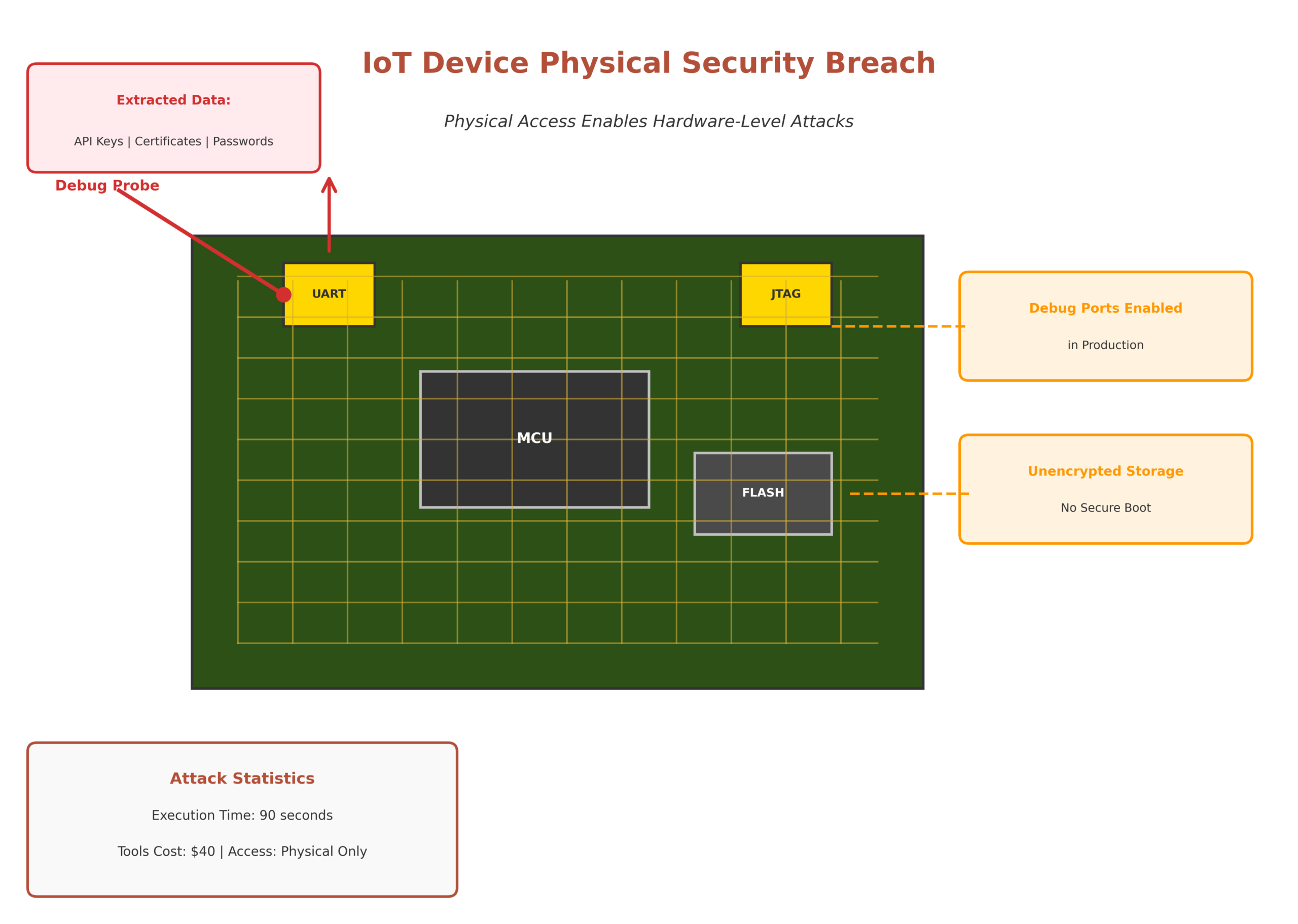

Physical access to IoT devices changes everything. Unlike servers in locked data centers, IoT devices sit in parking lots, forests, customer premises, and public spaces where attackers have unlimited time and physical access.

We’ve extracted root credentials from devices in under 90 seconds using $40 tools. Device-level security requires assuming the attacker has unlimited physical access and infinite time. The question isn’t “can they break in?” but “is breaking in worth their effort?” Device security is about making extraction economically unfeasible relative to the value gained, not making it theoretically impossible.

Physical Security Realities:

- Debug Interfaces: UART, JTAG, SWD ports provide direct firmware access

- Storage Extraction: Flash chips can be physically removed and read

- Side-Channel Attacks: Power analysis reveals cryptographic keys

- Time Advantage: Attackers have weeks to analyze captured devices

- Hardcoded Credentials: Remain the most common vulnerability we discover in audits

- Debug Ports: Left enabled in production provide root access within minutes

- Unencrypted Storage: Exposes certificates, tokens, and configuration data

- Secure Boot: Disabled or improperly configured allows firmware replacement

“Device security isn’t about making extraction impossible—it’s about making it economically unfeasible relative to the value gained.”

Smart Building Penetration Test: During a penetration test for a smart building client, our team extracted Wi-Fi credentials, API tokens, and device certificates from a wall-mounted sensor in 3 minutes using a UART interface. The manufacturer had shipped 15,000 units with debug mode enabled. The retrofit required replacing hardware in every deployed unit at a cost exceeding $800,000.

4. Firmware Vulnerabilities and Update Risks

Firmware sits at the intersection of our biggest challenges: it’s hard to update, critical to security, and prone to vulnerabilities. The paradox of IoT security is that the cure—remote updates—can be weaponized into the attack.

We’ve managed fleets where firmware updates were more dangerous than the vulnerabilities they fixed. A compromised update mechanism doesn’t just fail to fix vulnerabilities—it becomes the vulnerability that compromises your entire fleet simultaneously. The update infrastructure requires the same security rigor as the devices themselves, yet often receives far less attention during design.

Update Mechanism Requirements:

- Cryptographic Signing: Every firmware image must be signed with manufacturer private key

- Secure Transport: TLS 1.3+ for all update downloads

- Rollback Protection: Prevent downgrading to vulnerable firmware versions

- Atomic Updates: Either fully succeed or fully fail—no partial states

- Unpatched Devices: Remain vulnerable indefinitely in disconnected deployments

- OTA Security: Update mechanisms without signature verification enable malicious firmware injection

- Fleet Bricking: Failed updates can disable entire device fleets simultaneously

- Rollback Vulnerabilities: Allow downgrading to exploitable firmware versions

“A compromised update mechanism doesn’t just fail to fix vulnerabilities—it becomes the vulnerability that compromises your entire fleet simultaneously.”

Logistics OTA Compromise: A logistics client’s OTA update server was compromised, pushing malicious firmware to 8,000 GPS trackers. The attacker used the update mechanism itself—designed for security—as the attack vector. Recovery required physically collecting devices from 400 delivery vehicles across 12 states over three weeks. Total incident cost: $1.2M in operational downtime and device recovery.

5. Weak Device Identity and Authentication

Device identity in IoT is fundamentally broken in most implementations we audit. Shared credentials across device fleets, certificate management nightmares, and identity spoofing create systemic vulnerabilities that compromise entire deployments through single-device breaches.

The challenge isn’t technical—it’s operational. Managing unique identities for 100,000 devices over 10 years requires infrastructure most organizations don’t build until after a breach. We’ve seen the pattern repeatedly: developers choose shared credentials for deployment convenience, operations teams lack tools for certificate rotation, and five years later a single compromised device exposes the entire fleet. The irony is that proper identity infrastructure costs less than most post-breach remediations, but organizations consistently defer the investment until forced by incident response.

Identity Architecture Requirements:

- Unique Credentials: Every device needs cryptographically unique identity provisioned during manufacturing

- PKI Infrastructure: Certificate authority capable of managing millions of device certificates

- Rotation Capability: Ability to update credentials without physical access

- Revocation System: Instant invalidation of compromised device identities

- Shared API Keys: Enable single-compromise fleet exploitation across entire device models

- Certificate Expiration: Without rotation mechanisms creates mass authentication failures

- Device Attestation: Lack of attestation allows counterfeit devices to join networks

- Identity Binding: Weak binding enables device impersonation and MITM attacks

“If your devices share credentials, you don’t have device security—you have theater security. One compromise is all compromises.”

Energy Monitoring Certificate Sharing: An energy monitoring client used the same TLS certificate across 25,000 devices. When a single device was reverse-engineered, the extracted certificate compromised the entire fleet. Attackers registered 400 spoofed devices that reported false consumption data. The 9-month remediation required hardware replacement and cost $2.1M—far exceeding what proper PKI infrastructure would have cost initially.

6. Network and Communication Security Threats

IoT communication happens over networks you don’t control using protocols designed before security was a concern. The weakest network link determines your overall security posture, regardless of how well you secure other components.

We’ve built systems communicating over LoRaWAN, cellular, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and industrial protocols—each with distinct vulnerability profiles. The challenge isn’t choosing the “most secure” protocol—it’s designing communication that remains secure when transmitted over completely untrusted networks. Network security in IoT isn’t about building walls; it’s about assuming the walls don’t exist and designing accordingly.

| Protocol Type |

Primary Vulnerability |

Mitigation Strategy |

| Industrial (Modbus, BACnet) |

No native encryption |

Application-layer encryption + network segmentation |

| Cellular (LTE-M, NB-IoT) |

Baseband exploits |

End-to-end encryption independent of carrier |

| Short-range (BLE, Zigbee) |

Physical proximity attacks |

Secure pairing + re-authentication |

| Wi-Fi |

Rogue access points |

Certificate pinning + mutual TLS |

- MITM Attacks: Trivial on unencrypted protocols still common in industrial IoT

- Rogue Gateways: Intercept and modify device communication

- Packet Injection: Possible on many industrial and IoT-specific protocols

- Network Segmentation: Failures allow lateral movement from IoT to corporate networks

“Network security in IoT isn’t about building walls—it’s about assuming the walls don’t exist and designing communication that remains secure even when fully observed.”

Smart Agriculture Modbus Interception: A smart agriculture deployment used Modbus RTU without encryption. Attackers 200 meters away intercepted irrigation commands using a $150 SDR, causing $90,000 in crop damage over two weeks before detection. The incident revealed that protocol-level security, not just network-level, is essential for operational integrity in physically accessible deployments.

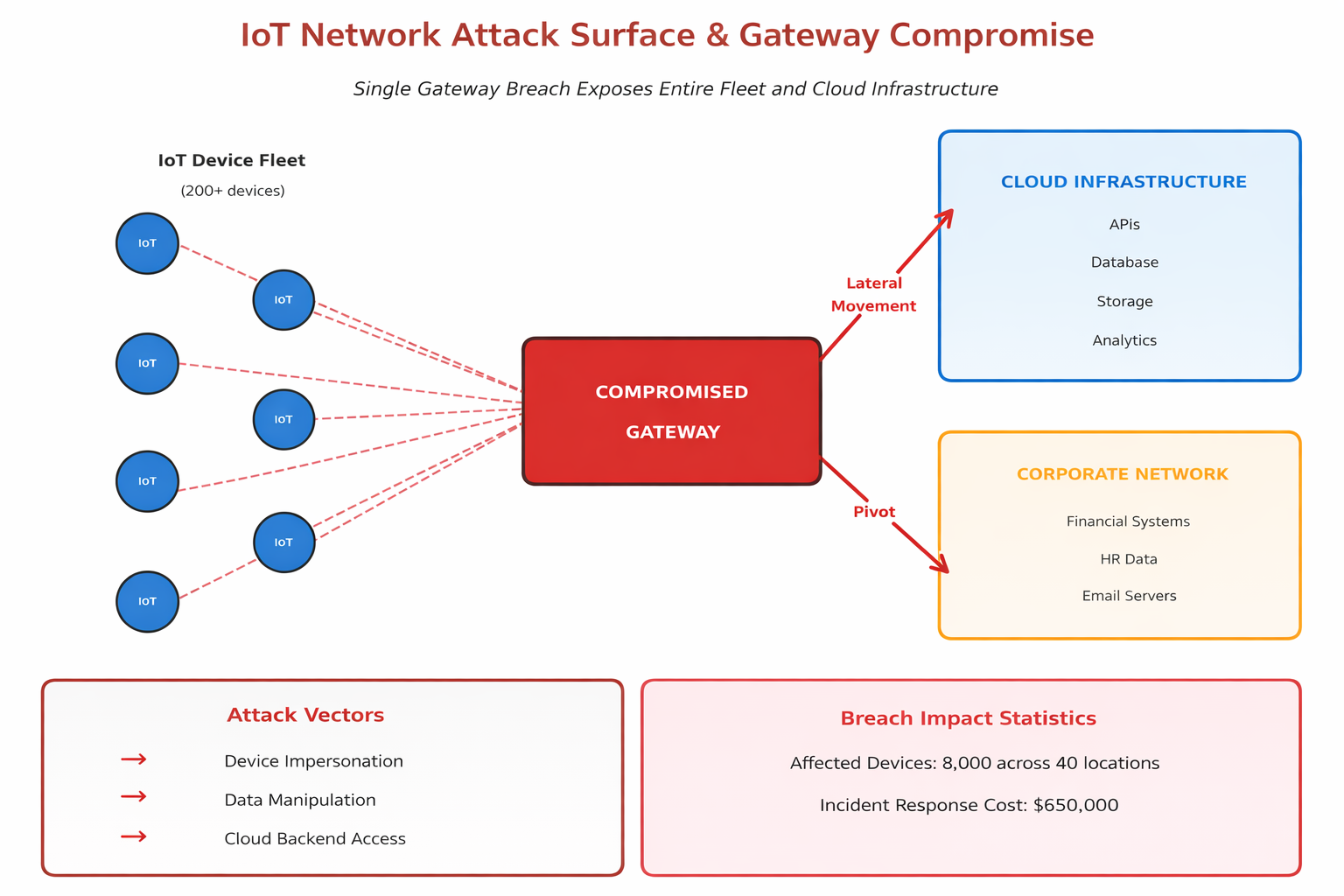

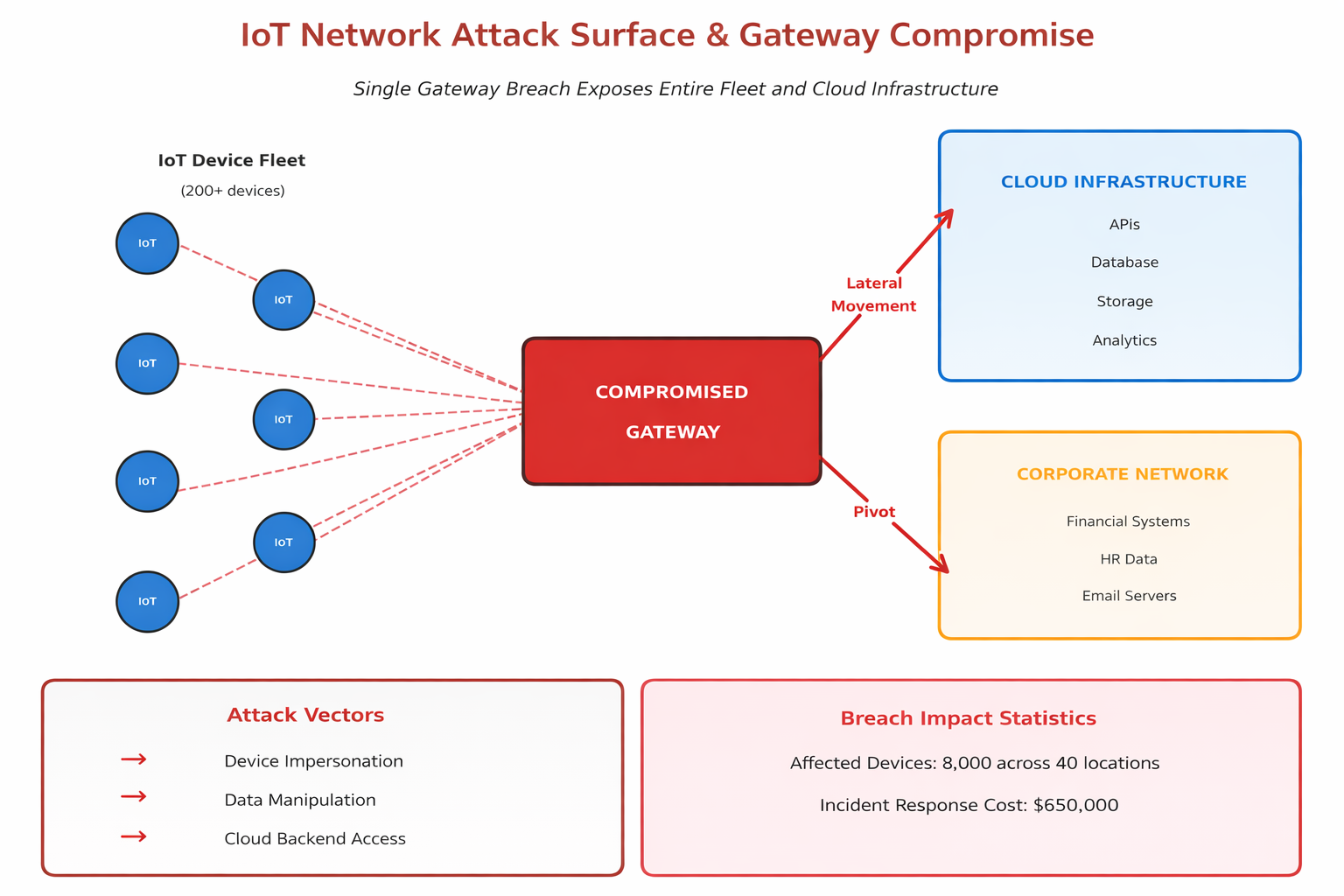

7. Gateway as a High-Value Attack Target

Gateways aggregate trust, making them catastrophic single points of failure. A compromised gateway can intercept data from hundreds of devices, inject commands, manipulate telemetry, and pivot to backend systems.

We’ve seen gateway compromises that exposed entire facilities because the gateway had excessive permissions and insufficient monitoring. The security challenge with gateways is they sit at the intersection of untrusted edge devices and trusted cloud infrastructure. They need privileges to manage devices but shouldn’t have unfettered access to backend systems. Most implementations fail this balance catastrophically.

Gateway Security Architecture:

- Credential Isolation: Gateways hold device credentials, never cloud admin credentials

- Least Privilege: API access limited to specific device management functions

- Network Segmentation: Gateway-to-cloud traffic isolated from device-to-gateway

- Monitoring: All gateway administrative actions logged and alerted

- Lateral Movement: From gateway to cloud backend common in flat network architectures

- Credential Theft: Gateway compromise provides fleet-wide device impersonation capability

- Data Manipulation: At gateway layer bypasses device-level security entirely

- Physical Access: Often easier to gateways than distributed edge devices

“Gateways are force multipliers for attackers—they concentrate access, privileges, and data in a single compromise target that’s often the least hardened component.”

Retail Building Management Breach: A retail client’s building management system had 40 gateways, each managing 200+ devices. One compromised gateway with overly broad cloud permissions allowed attackers to access the entire cloud infrastructure, affecting all 8,000 devices across 40 locations. The breach cost $650,000 in incident response and revealed that gateway security required the same rigor as cloud infrastructure security.

8. Cloud API and Backend Exposure

We’ve seen more IoT breaches originate from poorly secured cloud APIs than from device vulnerabilities. The backend often becomes the soft target because developers focused on device hardening forget that cloud endpoints process device data with elevated privileges.

API security in IoT differs from web APIs because IoT APIs handle commands that control physical systems, not just data queries. A SQL injection in a web app leaks data. A command injection in an IoT API might unlock doors, disable alarms, or shut down industrial equipment. The stakes are fundamentally different, but the security practices often aren’t.

IoT API Security Best Practices:

- ✓ DO: Implement per-device authorization, not just authentication

- ✓ DO: Rate limit based on device identity and command type

- ✓ DO: Log all commands with full context for forensics

- ✗ DON’T: Allow any device to query data from any other device

- ✗ DON’T: Trust device-provided timestamps without validation

- ✗ DON’T: Expose administrative functions through device APIs

- Excessive Permissions: Allow single compromised device to access fleet-wide data

- Token Leakage: From devices provides backend access without device compromise

- Privilege Escalation: Through device APIs enables administrative access

- Rate Limiting Gaps: Enable denial-of-service against critical operational systems

“Cloud APIs in IoT systems aren’t just interfaces—they’re remote control systems for physical infrastructure. Treat them accordingly.”

Fleet Management API Authorization Failure: A fleet management client’s API had no per-device authorization—any device could query or command any other device. An attacker who compromised one vehicle tracker gained control over 6,000 vehicles, including engine shutoff capabilities. The vulnerability existed for 14 months before discovery, demonstrating that API security testing must include authorization logic, not just authentication.

9. Data Privacy and Leakage Risks

IoT telemetry reveals patterns that privacy frameworks weren’t designed to address. Location data, usage patterns, sensor readings, and metadata inference create privacy exposure beyond traditional PII.

We’ve built systems where anonymized sensor data could still identify individuals through behavioral analysis. The challenge is that privacy violations in IoT happen in the patterns between data points, not just in the data itself. Energy consumption patterns reveal when homes are occupied. Temperature sensor data reveals room usage. Pressure sensor timing reveals manufacturing processes. All of this constitutes personal or proprietary information under various regulations, yet it’s collected as “anonymous telemetry.” Privacy in IoT requires understanding what the data reveals, not just what it explicitly contains, and designing collection, retention, and access controls accordingly.

Privacy Risk Categories:

- Direct PII: Names, addresses, device identifiers linked to individuals

- Behavioral Inference: Patterns that reveal personal habits and routines

- Cross-Device Correlation: Linking anonymous data through timing and location

- Derivative Data: Analytics that create new privacy-sensitive insights

- Metadata Leakage: Timing and frequency analysis reveals user behavior patterns

- Cross-Device Correlation: Enables identification despite anonymization

- Telemetry Aggregation: Creates derivative data requiring its own protection

- Regulatory Compliance: Gaps between data collection and retention policies

“In IoT, privacy violations happen in the patterns between data points, not just in the data itself. Protecting privacy requires understanding what the data reveals, not just what it contains.”

Smart Home GDPR Violation: A smart home client collected “anonymized” energy usage data. When regulators audited the system, pattern analysis revealed household occupancy, appliance usage, and daily routines with 94% accuracy—all considered personal data under GDPR. The $280,000 compliance violation and forced architectural redesign taught us that privacy analysis must include what data reveals, not just what it explicitly contains.

10. Time-Series Data Abuse and Manipulation

IoT generates time-series data that drives operational decisions. Data manipulation attacks target this temporal dimension—false readings, timestamp tampering, and analytics poisoning create business impact that accumulates invisibly over weeks or months.

We’ve investigated incidents where manipulated sensor data caused millions in losses before anyone questioned the data’s integrity. The insidious aspect of time-series attacks is they don’t create obvious breaches or system failures—they corrupt decision-making gradually. By the time the manipulation is discovered, months of operational decisions have been based on false data.

Time-Series Attack Vectors:

- False Data Injection: Reporting incorrect sensor values within plausible ranges

- Timestamp Manipulation: Altering when data was actually collected

- Data Poisoning: Gradually skewing analytics and ML models

- Replay Attacks: Re-sending old valid data to hide current conditions

- Analytics Corruption: Skews insights and creates misleading operational intelligence

- ML Poisoning: Consistent false inputs corrupt machine learning models

- Delayed Detection: Gradual drift rather than sudden anomalies prevents early discovery

- Decision Impact: Operational choices based on corrupted data compound over time

“Time-series manipulation is insidious—the damage accumulates in business decisions made on corrupted data, not in the technical breach itself.”

Industrial Production Optimization Failure: An industrial client’s production optimization relied on sensor telemetry. Manipulated temperature readings over 6 months caused gradual quality degradation, resulting in $1.8M in rejected products before root cause analysis revealed the data integrity issue. The incident demonstrated that data validation must include temporal consistency checks, not just range validation.

11. Edge Computing Security Challenges

Edge computing brings processing closer to devices but also brings new attack surfaces. Edge nodes combine the worst of both worlds—they’re physically accessible like devices but hold valuable assets like cloud systems.

We’ve deployed edge inference systems that seemed secure until we discovered model theft, local data exposure, and tampering attacks. The security challenge isn’t technical capability but operational reality across distributed edge infrastructure. Edge computing distributes the benefits of local processing but also distributes the security burden to locations where you have minimal control and maximum exposure.

Edge Security Challenges:

- ML Model Protection: Edge nodes hold valuable algorithms vulnerable to extraction

- Local Storage: Processed data stored locally creates compliance risks

- Performance vs Security: Encryption overhead conflicts with latency requirements

- Physical Accessibility: Edge locations often unsecured like devices

- Model Extraction: From edge nodes exposes proprietary algorithms and training data

- Inference Tampering: Manipulates results without attacking source data

- Storage Compliance: Unsecured edge storage creates data retention violations

- Synchronization Vulnerabilities: Edge-to-cloud sync enables data manipulation in transit

“Edge computing distributes the benefits of local processing but also distributes the security burden to locations where you have minimal control and maximum exposure.”

Retail Analytics Model Theft: A retail analytics client deployed computer vision models to 300 edge devices. Within four months, competitors extracted the models from physically accessible devices, copying $400,000 in ML development investment. The models were stored unencrypted because encryption impacted inference performance. This taught us that edge security requires choosing between performance and protection—there’s rarely a free lunch.

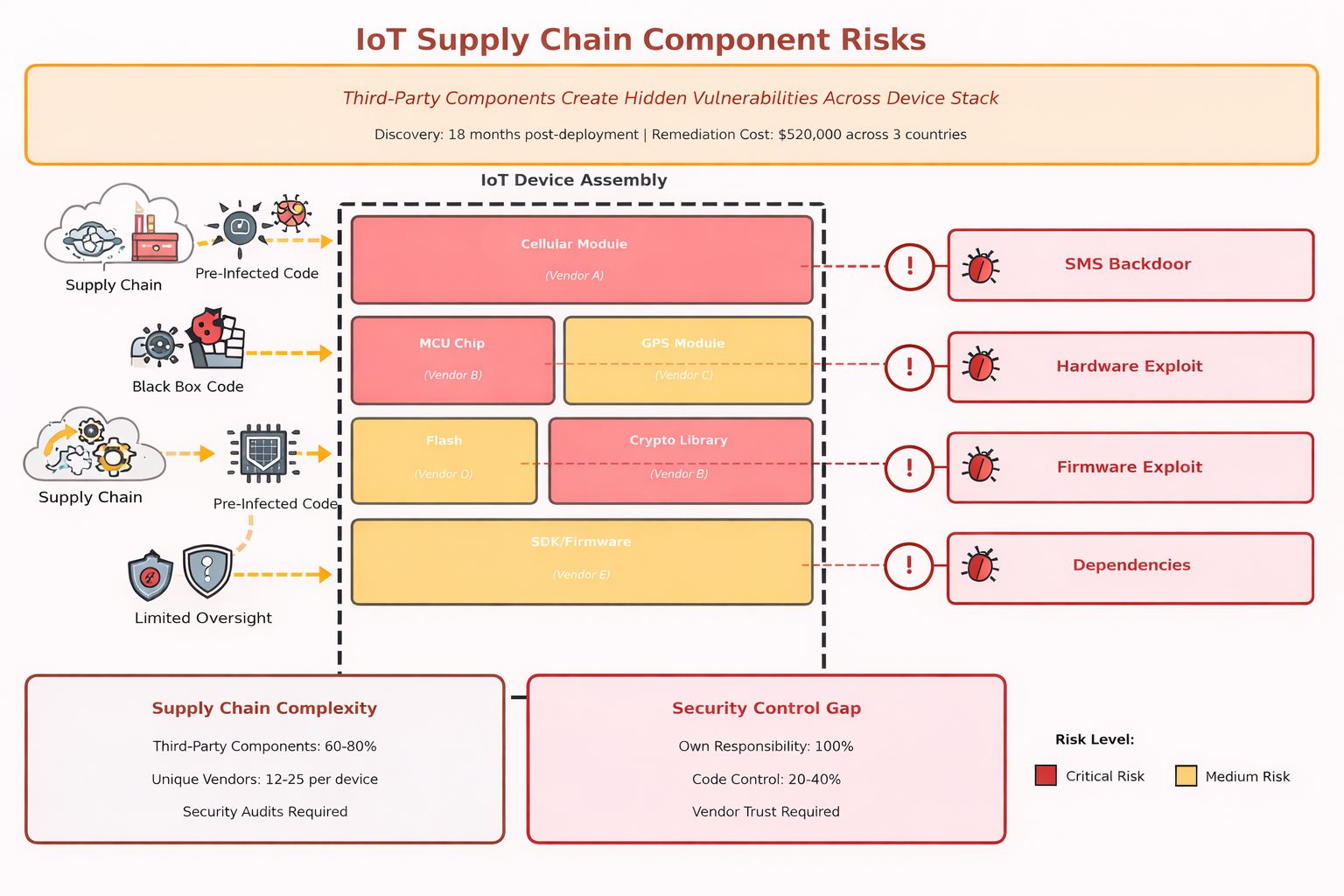

12. Supply Chain and Third-Party Component Risks

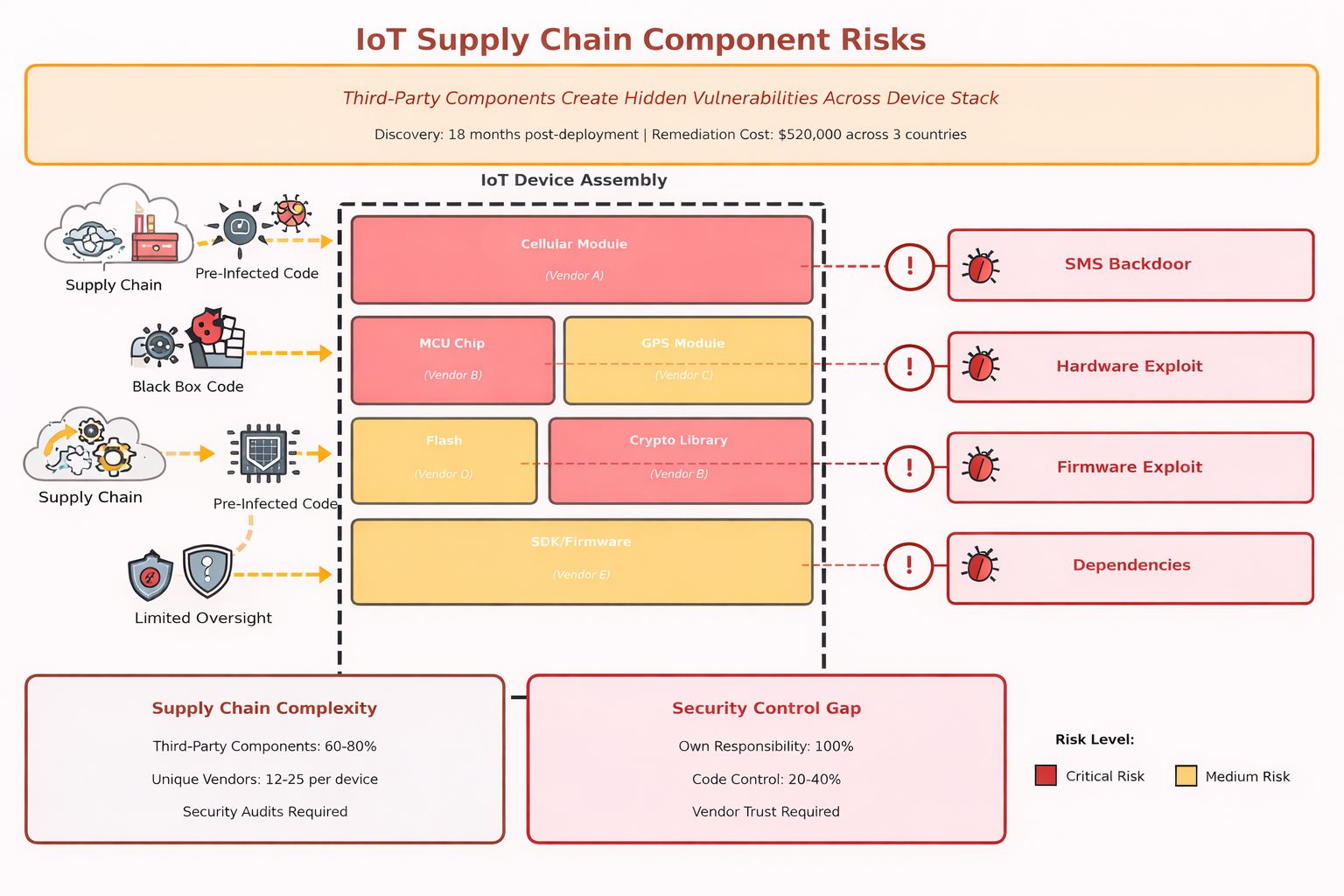

Every IoT device contains components from dozens of vendors—chips, firmware libraries, SDKs, cellular modules, sensors. You own the security responsibility but lack control over 60-80% of the code and components in your devices.

We’ve discovered backdoors, hardcoded credentials, and vulnerabilities deep in supply chain components that we had no visibility into until security incidents occurred. The challenge is that supply chain security requires trusting vendors you’ve never met with security decisions that can compromise your entire deployment. Component manufacturers optimize for features and cost, not security. SDK developers don’t know your threat model. Chip vendors support hundreds of customers with varying security requirements. The result is that security assumptions made by component vendors rarely align with security requirements of your specific deployment, but you don’t discover the mismatch until after manufacturing.

| Supply Chain Layer |

Security Risk |

Detection Difficulty |

| Silicon/Chips |

Hardware backdoors, undocumented features |

Extremely High – requires advanced analysis |

| Firmware Libraries |

Vulnerabilities, hardcoded credentials |

High – need source code access |

| SDKs/Frameworks |

Transitive dependencies, update mechanisms |

Medium – can audit dependencies |

| Manufacturing |

Component substitution, malicious modifications |

High – requires supply chain visibility |

- Firmware Libraries: Contain vulnerabilities you can’t patch independently

- Chip-Level Backdoors: Discovered years after deployment in widely-used components

- SDK Dependencies: Create transitive vulnerabilities through entire dependency chains

- Manufacturing Compromise: Introduces hardware modifications before you receive devices

“Supply chain security in IoT is trust delegation at massive scale—you’re trusting vendors you’ve never met with security decisions that can compromise your entire deployment.”

Transportation GPS Backdoor: A transportation client discovered their GPS module vendor had embedded a diagnostic backdoor accessible via SMS. The backdoor existed in 12,000 deployed devices for 18 months before discovery during a security audit. The vendor claimed it was for “field support.” Remediation required firmware updates to devices across three countries at a cost of $520,000, demonstrating that vendor security practices must be audited, not assumed.

13. Insider Threats in IoT Operations

Insider threats in IoT extend beyond traditional corporate espionage. The distributed nature of IoT operations creates insider risk across installation teams, maintenance contractors, and regional operations staff who have both physical and administrative access.

We’ve seen field technicians install rogue devices, operators misconfigure access controls exposing entire fleets, and contractors retain administrative credentials years after projects end. IoT insider threats are harder to manage than traditional IT because the insiders include field installation teams, maintenance contractors, and regional operations staff—not just your employees.

Insider Threat Vectors:

- Physical Access: Installation and maintenance teams handle devices directly

- Administrative Credentials: Operations staff require elevated permissions

- Contractor Access: Third-party installers need temporary high privileges

- Regional Operations: Distributed teams harder to monitor centrally

- Role Separation: Weak separation gives field technicians unnecessary cloud administrative access

- Credential Retention: Contractors maintain access after project completion

- Malicious Installation: Insiders with physical access can compromise devices at scale during deployment

- Access Misconfiguration: Common when operations teams lack security training

“IoT insider threats are harder to manage than traditional IT because the insiders include field installation teams, maintenance contractors, and regional operations staff—not just your employees.”

Smart City Contractor Shadow Network: A smart city project discovered a contractor who installed 40 unauthorized cellular gateways during official installations, creating a shadow network for selling stolen bandwidth. The contractor had legitimate physical access and used official equipment, making detection nearly impossible until unusual traffic patterns emerged 8 months later. The incident cost $180,000 in investigation, device removal, and process redesign.

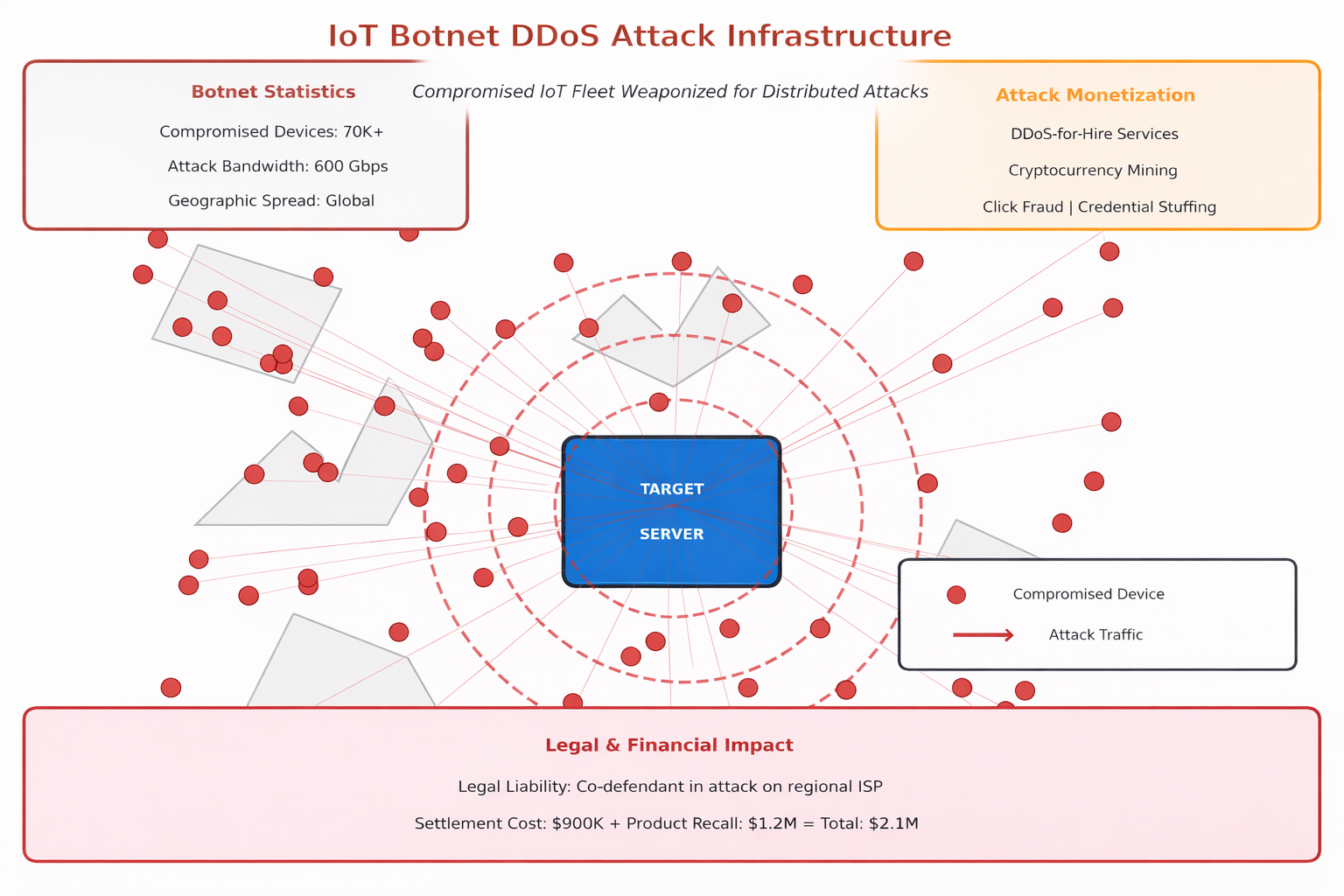

14. Large-Scale Botnets and Fleet Exploitation

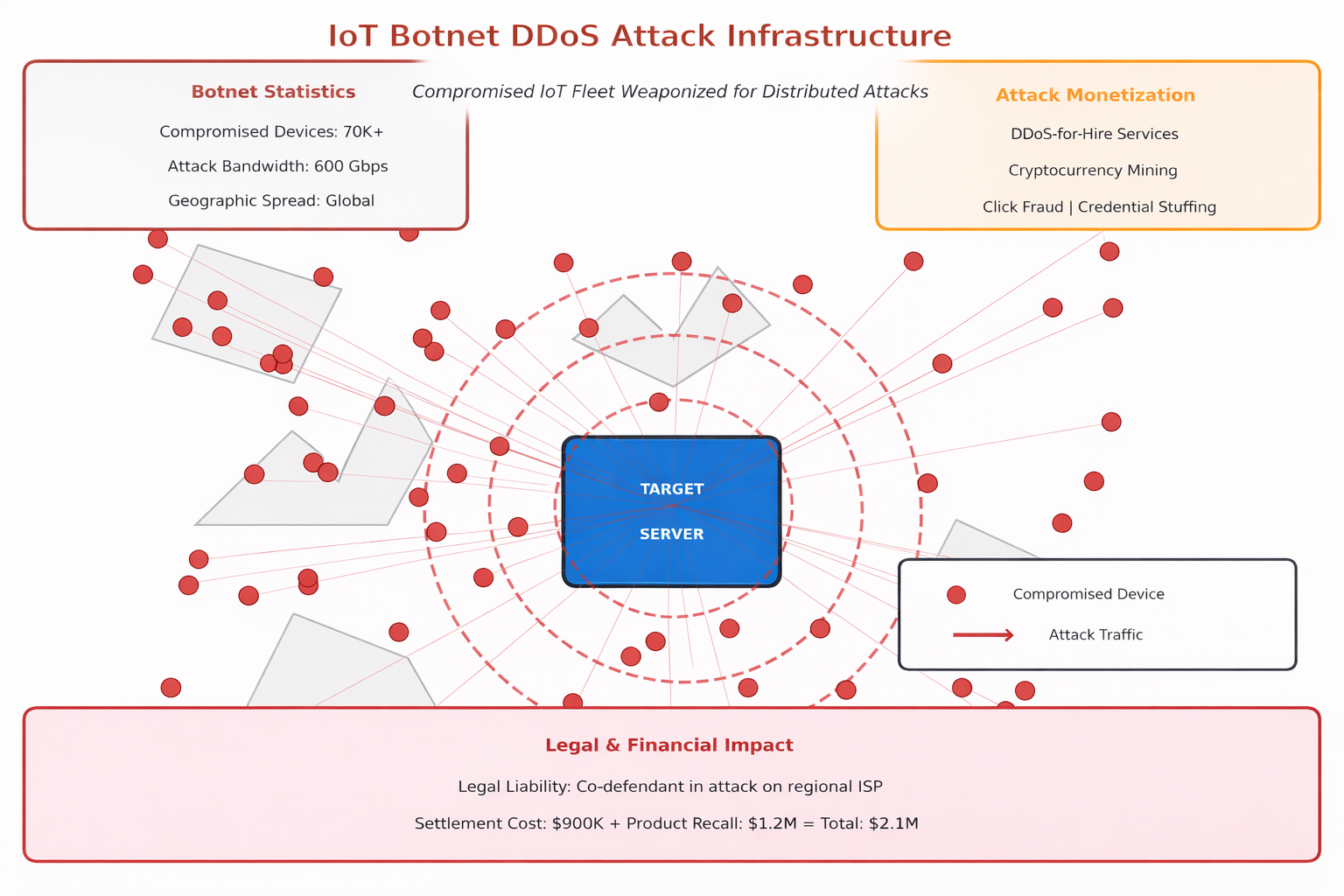

Compromised IoT devices get weaponized into botnets that launch attacks far beyond the original deployment. When your IoT fleet becomes a botnet, you’re no longer the victim—you’re the weapon being used to attack others, and you carry the legal and financial consequences.

We’ve seen clients whose devices participated in DDoS attacks against third parties, creating legal liability and reputational damage. The economics are brutal—attackers spend weeks compromising your fleet to launch attacks worth millions in ransom or fraud, while you bear the costs of remediation, legal liability, and brand damage.

Botnet Monetization Methods:

- DDoS-for-Hire: Renting attack capacity to third parties

- Cryptocurrency Mining: Using device compute and power

- Click Fraud: Generating fake ad impressions

- Credential Stuffing: Using device IPs to avoid detection

- Fleet-Wide Compromise: Enables massive DDoS attacks using your infrastructure

- Resource Theft: Devices become cryptocurrency mining nodes draining power and bandwidth

- Legal Liability: When your devices attack critical infrastructure or government systems

- Reputational Damage: Brand becomes associated with cybercrime infrastructure

“When your IoT fleet becomes a botnet, you’re no longer the victim—you’re the weapon being used to attack others, and you carry the legal and financial consequences.”

Home Automation Botnet Legal Action: A home automation client’s devices were recruited into a botnet that attacked a regional ISP. Legal action named our client as co-defendant due to negligent security. The devices had default credentials and no firmware update mechanism. Settlement costs exceeded $900,000, plus $1.2M for forced product recall and redesign. The incident taught us that device security isn’t just about protecting your own infrastructure—it’s about preventing your products from becoming attack platforms.

15. Compliance and Regulatory Security Risks

IoT deployments trigger regulatory requirements that traditional IT doesn’t face. Compliance isn’t a checkbox—it’s an architectural constraint that must drive design decisions from the beginning.

We’ve managed projects where compliance penalties exceeded the entire project budget because security requirements weren’t understood during architecture design. The challenge is that IoT deployments often trigger multiple regulatory frameworks simultaneously—GDPR for personal data, HIPAA for health devices, industry-specific standards like IEC 62443, and regional certification requirements. These frameworks have potentially conflicting requirements, and retrofitting compliance into deployed systems costs 10-50x more than designing for compliance initially. Regulatory compliance in IoT isn’t about passing audits—it’s about designing systems where compliance is architecturally impossible to violate through configuration or operation.

| Regulation |

Trigger Condition |

Key Requirement |

Penalty Range |

| GDPR |

EU citizen data |

Consent, data minimization, right to deletion |

Up to €20M or 4% revenue |

| HIPAA |

Health information (US) |

Encryption, access controls, breach notification |

Up to $1.5M per violation |

| IEC 62443 |

Industrial systems |

Defense in depth, security levels |

Market access denial |

| UL 2900 |

Connected products |

Software testing, vulnerability disclosure |

Certification denial |

- GDPR Violations: Through improper data collection, retention, or cross-border transfer

- HIPAA Penalties: For health monitoring devices with insufficient data protection

- Industry Standards: IEC 62443, UL 2900 required for market access in specific sectors

- Regional Certification: Requirements varying by deployment geography

“Regulatory compliance in IoT isn’t about passing audits—it’s about designing systems where compliance is architecturally impossible to violate through configuration or operation.”

Healthcare Wearable GDPR Fine: A healthcare wearable client faced €2.4M in GDPR fines when their device architecture allowed cloud administrators to access unencrypted patient data. The violation wasn’t malicious—it was architectural. The system required complete redesign with hardware-level encryption and zero-knowledge cloud architecture. Total compliance remediation cost exceeded €5M, demonstrating that compliance requirements must drive architecture decisions, not be retrofitted afterward.

16. Common IoT Security Anti-Patterns

After two decades, we see the same security anti-patterns repeatedly. These patterns seem efficient during development but create systematic vulnerabilities that are expensive or impossible to fix post-deployment.

Recognizing anti-patterns early is often more valuable than implementing specific security controls. The anti-patterns are seductive because they simplify development and deployment. The complexity they defer emerges as security incidents, technical debt, and impossible-to-fix architectural flaws.

| Anti-Pattern |

Why It Happens |

Why It Fails |

Fix Cost Multiplier |

| Security as Afterthought |

Focus on features first |

Architecture can’t support security requirements |

10-50x |

| Flat Networks |

Simpler to configure |

Single breach exposes everything |

8-15x |

| Shared Credentials |

Easy deployment |

One compromise = all compromises |

20-100x |

| No Monitoring |

“Devices just work” |

Breaches undetected for months |

Incident cost 5-10x |

- Security Bolted On: Added during compliance review instead of architecture phase

- Flat Network Design: Allows compromised IoT devices to access corporate infrastructure

- Shared Secrets: Distributed across device fleets for deployment convenience

- Missing Monitoring: No security monitoring because devices are “dumb” or “low-risk”

“IoT security anti-patterns are seductive because they simplify development and deployment. The complexity they defer emerges as security incidents, technical debt, and impossible-to-fix architectural flaws.”

Building Automation Flat Network Breach: A building automation client deployed with flat networking for “simplicity”—all devices on the same VLAN as building management workstations. One compromised HVAC sensor provided access to financial systems through lateral movement. The breach went undetected for 6 months, resulting in $1.1M in incident response and complete network redesign. The anti-pattern was identified during initial architecture review but dismissed as “over-engineering.” The redesign cost 8x more than proper segmentation would have cost initially.

17. Incident Detection and Blind Spots in IoT

IoT breaches often go undetected for months because traditional security monitoring doesn’t work for distributed devices. The challenge isn’t lack of tools—it’s fundamental mismatches between security monitoring models and IoT operational reality.

We’ve investigated incidents where devices were compromised for over a year before detection. Traditional security monitoring assumes network perimeter protection and endpoint visibility—assumptions that completely break down in distributed IoT deployments. Device behavior is highly variable based on environmental conditions, making behavioral anomaly detection prone to false positives. Network monitoring is blind to device-level compromises when encryption hides payloads. Log aggregation is insufficient when devices operate offline for extended periods. The result is that security teams either get overwhelmed by false positives and ignore IoT monitoring, or they have no IoT-specific monitoring at all. Both scenarios mean breaches continue undetected until operational impact becomes obvious.

IoT Detection Challenges:

- Behavioral Variability: Legitimate device behavior varies widely making anomaly detection unreliable

- Encryption Blindness: Network monitoring can’t inspect encrypted device-to-cloud traffic

- Offline Operations: Devices operating disconnected generate logs with massive delays

- Alert Fatigue: High false positive rates cause teams to ignore IoT alerts

- Behavioral Anomaly Detection: Fails due to high variability in legitimate device behavior

- Network Monitoring: Blind to device-level compromises when encryption hides payloads

- Log Aggregation: Insufficient when devices operate offline for extended periods

- Alert Fatigue: False positives lead security teams to ignore IoT monitoring

“IoT security blind spots aren’t about missing tools—they’re about fundamental mismatches between how security teams monitor threats and how IoT devices actually operate in the field.”

Industrial Sensor Data Manipulation: An industrial client’s sensors were compromised and reporting false data for 11 months before detection. Traditional monitoring showed “normal” operation because the attack didn’t create network anomalies—it manipulated sensor calibration. Discovery only occurred when physical audits revealed discrepancies. The incident caused $3.2M in operational losses from decisions based on corrupted data, demonstrating that IoT monitoring must validate data integrity, not just network and system behavior.

18. Security Testing Gaps in IoT Projects

Standard penetration testing misses most IoT vulnerabilities. Web application pentests typically cover 20-30% of IoT attack surface—missing firmware, hardware, RF communications, physical security, and supply chain vectors.

We’ve seen systems pass pentests then fail catastrophically in deployment because the pentest only covered cloud APIs, not firmware, radio protocols, physical security, or supply chain. The testing gap isn’t about effort—it’s about expertise and scope misalignment between web application security and IoT system security. Passing a pentest gives false confidence because the test methodology was designed for web applications, not distributed hardware systems with decade-long operational lifecycles.

| Testing Domain |

Standard Pentest Coverage |

IoT Requirements |

| Cloud APIs |

✓ Comprehensive |

Authentication, authorization, rate limiting |

| Firmware |

✗ Rarely included |

Reverse engineering, vulnerability analysis |

| Hardware |

✗ Not included |

Debug interfaces, side channels, physical extraction |

| RF Protocols |

✗ Not included |

Protocol analysis, jamming, injection |

| Supply Chain |

✗ Not included |

Component audits, vendor security assessment |

- Firmware Analysis: Requires specialized tools and expertise rarely included in standard pentests

- urity: Needs hardware labs and RF analysis capabilities

- Supply Chain Verification: Requires vendor audits beyond code review

- Operational Security: Emerges over time and isn’t testable in pre-deployment environments

“Passing a pentest gives false confidence in IoT security because the test methodology was designed for web applications, not distributed hardware systems with decade-long operational lifecycles.”

Medical Device JTAG Vulnerability: A medical device client passed a comprehensive web application pentest covering all cloud APIs and user interfaces. Post-deployment, security researchers extracted patient data through a JTAG interface that was never tested. The vulnerability existed in hardware design—completely outside the pentest scope. The recall cost $4.8M and required redesigning circuit boards for 15,000 deployed devices, teaching us that IoT security testing must include hardware, firmware, and physical security, not just software APIs.

19. Business Impact of IoT Security Failures

IoT security failures create business impacts that traditional IT breaches don’t. They don’t just leak data—they shut down operations, create safety incidents, trigger product recalls, and destroy market trust in ways that can end companies.

We’ve seen IoT security incidents that destroyed companies—not through data loss but through operational consequences, legal liability, and complete loss of customer trust in product safety. The business impact extends far beyond the immediate technical breach. Manufacturing downtime when compromised devices must be taken offline costs thousands per hour. Safety incidents create legal liability that insurance doesn’t cover. Product recalls destroy margins and market position simultaneously. Reputational damage in safety-critical industries is often non-recoverable. A data breach might cost a few million in incident response and regulatory fines. An IoT security failure that enables physical harm or operational sabotage can end entire companies through compounded operational, legal, and reputational impact.

| Impact Category |

Direct Cost |

Indirect Cost |

Duration |

| Operational Downtime |

$10K-500K/day |

Lost customer trust, contract penalties |

Days to weeks |

| Product Recall |

$50-200 per device |

Brand damage, market share loss |

Permanent |

| Safety Incident |

Legal settlements $1M+ |

Insurance rate increases, market exit |

Years |

| Regulatory Violation |

Fines up to 4% revenue |

Ongoing compliance burden |

Ongoing |

- Operational Downtime: When compromised devices must be taken offline across facilities

- Safety Risks: Create legal liability when devices control physical systems

- Product Recalls: For unfixable security vulnerabilities in deployed hardware

- Reputational Destruction: In safety-critical industries where trust is non-recoverable

“IoT security failures don’t just leak data—they shut down operations, create safety incidents, trigger product recalls, and destroy market trust in ways that can end companies.”

Connected Vehicle Startup Collapse: A connected vehicle startup faced complete market collapse after security researchers demonstrated remote vehicle control vulnerabilities. The technical fix was feasible, but customer trust evaporated instantly. The company lost 80% market value in three weeks, faced class-action lawsuits, and ultimately sold assets for pennies on the dollar. The security vulnerability cost perhaps $2M to fix, but the business impact was $400M in destroyed enterprise value—demonstrating that IoT security failures create existential business risks, not just technical problems.

20. When IoT Security Risks Kill Projects Entirely

IoT projects die when unfixable security vulnerabilities are discovered after hardware is manufactured but before regulatory approval or customer acceptance testing—the worst possible timing for discovering critical flaws.

We’ve seen IoT projects cancelled mid-deployment when security risks became understood too late. The pattern is consistent: architecture locked in, devices manufactured, deployment underway, then security assessment reveals unfixable vulnerabilities. The choice becomes deploy with known critical risks or write off the investment. In regulated industries or safety-critical applications, there’s no choice—the project dies.

| Project Phase |

Security Activity |

Risk if Skipped |

| Concept |

Threat modeling |

Wrong architecture selected |

| Design |

Security architecture review |

Unfixable flaws in hardware/firmware |

| Prototype |

Security testing (hardware + firmware) |

Vulnerabilities embedded in design |

| Manufacturing |

Supply chain security audit |

Compromised components at scale |

| Deployment |

Penetration testing |

Too late—recall required |

- Hardware Vulnerabilities: Discovered too late for manufacturing changes

- Regulatory Certification: Failures due to security gaps in submitted designs

- Customer Security Audits: Revealing deal-breaker vulnerabilities before deployment

- Remediation Cost: Exceeding total project budget and timeline

“IoT projects die when security risks become apparent after the architecture is locked into hardware but before deployment proves business value—the worst possible timing for discovering critical flaws.”

Infrastructure Monitoring Startup Failure: An infrastructure monitoring client invested $8M in hardware design and manufactured 5,000 devices before enterprise customer security audit. The audit revealed the devices lacked secure boot and used shared TLS certificates—automatic failures for critical infrastructure deployment. Redesign required new silicon and 18-month delay. The customer walked, the startup burned through runway waiting for redesign, and the company folded. The $8M investment became worthless because security architecture wasn’t validated before hardware commitment.

21. How Mature Teams Approach IoT Security Risk Management

The best IoT teams we’ve worked with don’t have better tools or bigger budgets—they have different mindsets. Security is treated as architecture constraint from day one, not compliance checkbox before launch.

The difference between mature and immature IoT security isn’t technical—it’s organizational, cultural, and procedural. Mature teams prevent security problems; immature teams respond to security incidents. Mature teams identify and reject architectures based on security constraints during design reviews—before any code is written or hardware is selected.

| Practice |

Immature Approach |

Mature Approach |

| Security Expertise |

Separate security team consulted late |

Security architects in all design reviews |

| Threat Modeling |

Done before pentest |

Drives architecture and component selection |

| Component Selection |

Based on features and cost |

Security evaluation equal to functional evaluation |

| Testing |

Pentest before launch |

Security testing at each phase |

| Operations |

Reactive incident response |

Continuous monitoring and threat hunting |

- Security Architects: Involved in hardware selection and vendor evaluation

- Threat Modeling: Drives architecture decisions, not validates completed designs

- Distributed Expertise: Security knowledge across device, gateway, and cloud teams

- Operational Security: Designed into deployment procedures, not added afterward

“Mature IoT security isn’t about having better tools—it’s about having security expertise embedded in architecture, hardware selection, vendor evaluation, and operational procedures from project inception.”

Automotive Component Rejection: A mature automotive client rejected a cheaper cellular module during hardware selection because security review revealed the module’s update mechanism was vulnerable to MITM attacks. The decision added $4 per device but prevented potential fleet-wide compromise that could have cost hundreds of millions in recalls. Immature teams would have discovered this vulnerability during penetration testing—after 100,000 vehicles were manufactured. Mature teams discovered it during hardware selection—when changing components cost $4 instead of $400M.

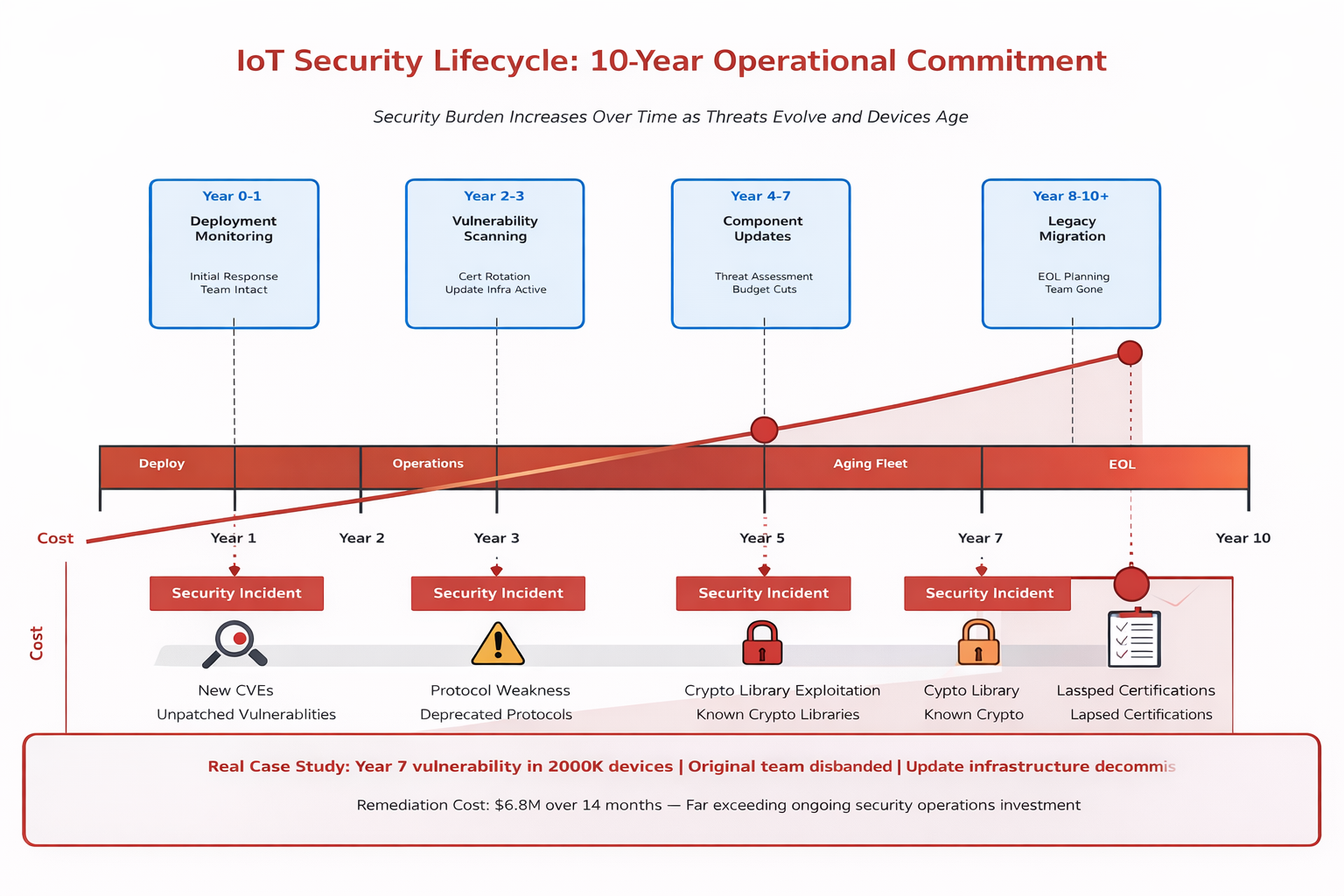

22. Security as an Ongoing Operational Discipline

IoT security doesn’t finish when devices deploy—it intensifies. Over 10-year device lifecycles, vulnerabilities emerge, threat landscapes evolve, compliance requirements change, and operational security degrades without active maintenance.

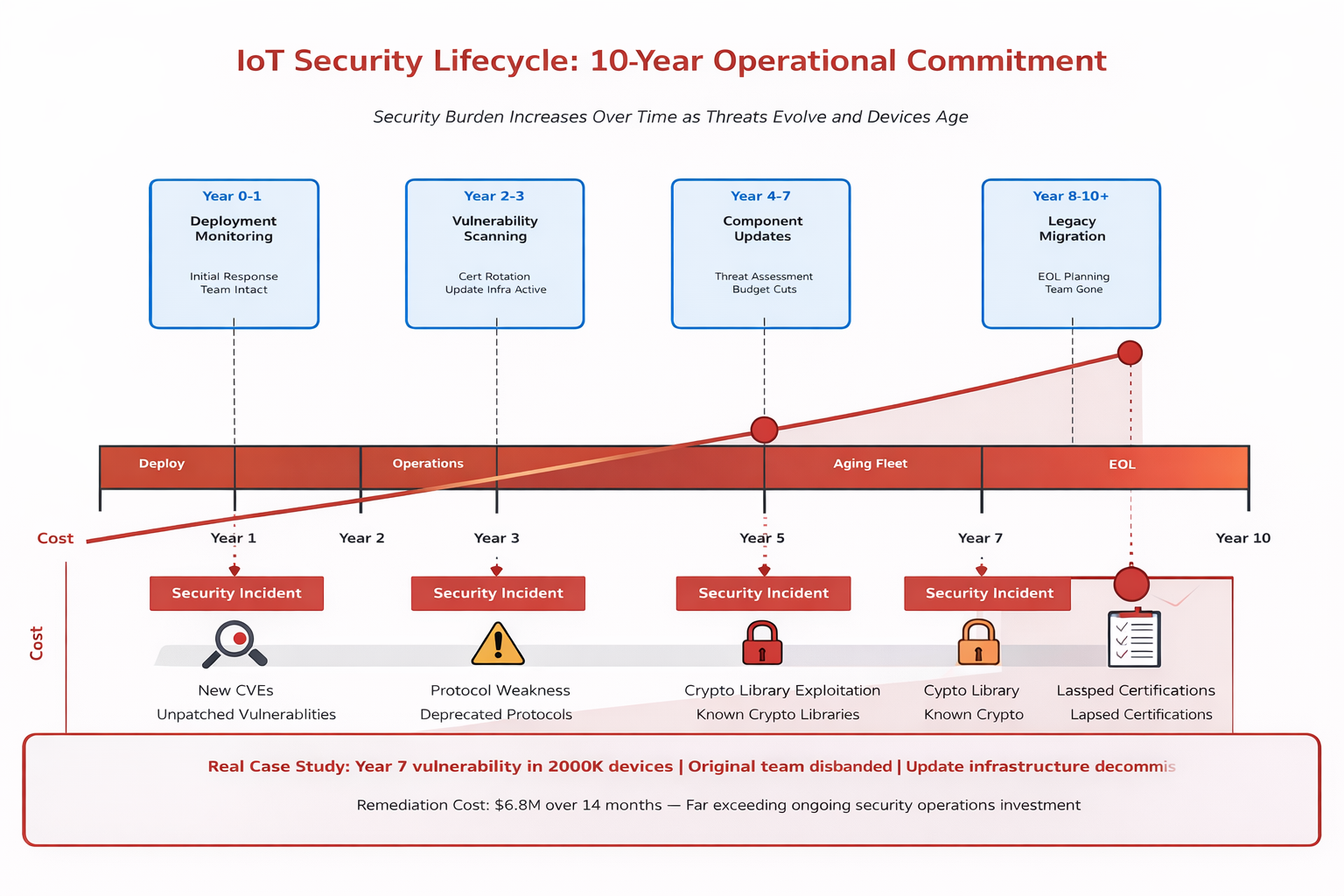

We manage deployments where the biggest security challenges emerged 3-5 years post-deployment, not during initial rollout. The challenge is that IoT security is a 10-year operational commitment, not a pre-deployment project phase. The security burden increases over time as threats evolve and devices age. Vulnerabilities discovered in component libraries three years after deployment still need patching. Compliance frameworks change, requiring architectural updates. Attack techniques evolve, making previously secure protocols vulnerable. Most organizations budget for development and deployment security but not for decade-long operational security, then face impossible choices when critical vulnerabilities emerge in deployed fleets years later with no budget or expertise to address them.

| Time Period |

Security Activities |

Common Failure |

| Year 0-1 |

Deployment monitoring, initial incident response |

Disbanding security team after launch |

| Year 2-3 |

Vulnerability scanning, certificate rotation |

Decommissioning update infrastructure to “save costs” |

| Year 4-7 |

Component library updates, threat reassessment |

No budget for ongoing security operations |

| Year 8-10+ |

Legacy protocol migration, end-of-life planning |

Original team gone, documentation lost |

- Vulnerability Monitoring: Continuous scanning for device components throughout lifecycle

- Threat Model Updates: Regular reassessment as attack techniques evolve

- Update Planning: Testing capabilities maintained for device fleet duration

- Incident Response: Procedures that account for physically distributed devices

“IoT security operational discipline means maintaining expertise, tools, monitoring, and response capabilities for the entire device lifecycle—often a decade or more after development teams have moved to other projects.”

Utility Smart Meter Vulnerability: A utility client deployed smart meters with 15-year lifespans. In year 7, a critical vulnerability was discovered in the cryptographic library used across 200,000 devices. The original development team had disbanded, documentation was incomplete, and update infrastructure had been decommissioned to “save costs.” Remediation took 14 months and cost $6.8M—far exceeding what maintaining operational security capabilities would have cost. The incident taught us that IoT security operations budget must span device lifecycle, not just development and deployment.

23. Final Perspective: Security Risk Is an Architecture Constraint

After twenty years building IoT systems, our core lesson is that security risk isn’t a feature you add or a test you pass—it’s an architectural constraint that shapes every decision from chip selection to cloud design.

Security determines which architectures are feasible, which deployments are viable, and which business models are sustainable. The most successful IoT projects treat security as fundamental constraint like power budget or network latency. The failed projects treated security as compliance task or penetration testing exercise. Security risk shapes IoT project success more than any other single factor we’ve observed. It’s not about whether your architecture can be built—it’s whether it can sustain security requirements over 10-year device lifecycles while threats evolve, regulations change, and operational costs compound. Most can’t. The projects that succeed are those where security constraints were understood and accepted during architecture, before hardware selection, before manufacturing commitments. The projects that fail are those where security was discovered to be impossible after the architecture was locked in hardware.

Security as Architectural Constraint:

- Chip Selection: Security requirements eliminate 60-80% of available components

- Network Topology: Security mandates drive segmentation and isolation requirements

- Cloud Architecture: Zero-trust and least-privilege not optional but fundamental

- Operational Model: Long-term security costs determine business viability

- Feasibility Analysis: Must include security operational costs over full device lifecycle

- Scalability Limits: Determined by security monitoring and update capabilities, not just technical capacity

- Long-term Viability: Based on ability to maintain security posture through evolving threats

- Business Model Impact: Security operational costs can exceed product revenue over lifecycle

“Security risk in IoT isn’t about being hacked—it’s about whether your architecture can sustain security requirements over 10-year device lifecycles while threats evolve, regulations change, and operational costs compound. Most can’t.”

Consumer IoT Business Model Failure: We evaluated a consumer IoT product that seemed technically brilliant—innovative features, good user experience, competitive pricing. Security analysis revealed the architecture required continuous security operations costing $40/device/year over a 10-year lifecycle to maintain acceptable risk posture. The product sold for $200. The math didn’t work—security operational costs over device lifetime exceeded total product revenue by 2x. The project was cancelled before production because security as architectural constraint made the business model non-viable. That’s the real impact of security risk—not breaches, but determining what’s possible to build sustainably.